The photo at the top of this page shows Penny at Grunau Regatta in 1962. © Sportverlag Gunther Rowell.

| Years (as a competitor) | 1960 (1x 4th) 1961 (1x 4th) 1962 (1x 2nd) 1963 (1x 4th) 1964 (1x 4th) |

| Clubs | Laleham Skiff and Punting Club, United Universities Women’s BC, Skiff Club, Burway RC, Thames Valley Skiff Club, Flushing and Mylor Pilot Gig Club |

| Height | 5’7.75″ or 172cm |

| Racing weight | 11 stone or 71kg |

| Born | 1942 |

Getting into rowing

Penny has been connected to the river Thames practically from birth. Although she was born in Scotland, her parents lived in West London until 1945. They had a weekend riverside bungalow on the Thames at Laleham in Surrey, and after her father was demobbed at the end of the Second World War, they decided to move there permanently because it was a much healthier environment for their children than bombed-out London.

An unattributed newspaper article about her early life, written in 1960 shortly before her first Women’s European Rowing Championships appearance, describes how, “More often than she not was found taking her afternoon nap in the dinghy at the bottom of the garden in preference to her pram,” which may be journalistic creativity, but is certainly eminently plausible.

An early experience in a punt in 1944 aged nearly three. (Photo: Penny Chuter’s personal collection.)

Rowing soon became a necessity as well as a recreation. “I had to row my little pulling dinghy across the river to primary school every day in the summer from the age of five – not in the winter if the Thames was in full spate – but otherwise that’s how I learned to row, ” she explains.

By that age she could swim across the Thames, having been taught by her mother who was a British champion long distance swimmer, and had been selected as a swimmer for the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles but hadn’t gone because the Olympic team was ‘required’ to travel first class but only given enough funding for a third class ticket, so the competitors were expected to pay the difference. Her father felt this was unacceptable, and although he could have afforded it, would not have been able to afford spending an equal amount on his five other children in due course, so he refused to pay and she never went. Penny says that although her parents would have been supportive of her rowing career anyway, her mother was particularly so because of this sad experience.

Skiffing and punting

Despite being keen on swimming, it proved an impractical sport for the young Penny as the nearest indoor pool was in Hammersmith. However her location was obviously ideal for river sports. In an interview published in World Sports magazine in September 1963, Penny admits that, “If I had lived anywhere except Laleham I would probably have taken up tennis or athletics… as it was, the opportunity to excel at rowing was there on the door step.”

She was unable to row at Burway RC, conveniently situated about 250m from her home, because it didn’t accept women members at that time, and so at the age of 12 she joined Laleham Skiff and Punting Club, which was also very close to where she lived and which she faithfully represented throughout her international sculling career. The impact of being forced down this route on her later rowing career cannot be underestimated because it provided her with an incredibly thorough grounding in the principles of how to move boats of different types, as well as far more racing experience than she would have had at a women’s rowing club at the time.

Punting. (Photo: Penny Chuter’s personal collection.)

As this account is about rowing rather than all the watersports activities that GB’s international rowers have participated in, this is not the place for a detailed biography of Penny’s success in skiffing and punting but, in summary, she secured the first of her 27 Punting Championship wins (across Ladies Singles, Ladies Doubles and Mixed Doubles) at the age of just 15 in 1957, and the first of 21 Skiff Championship wins (again, across all three disciplines) in 1958. Because of the rowing connection, it’s worth noting that all seven of her Ladies Double Skiff Championships titles were won with partners who also rowed in GB crews: 1959, 1960, 1961 and 1964 with Rosemary Gale; 1962 and 1963 with Zona Howard; and 1966 with Jean Wilshee although there are different variants on chickens and eggs here: Rosemary was a skiffer who was pulled into the GB quad for the 1960 European Women’s Rowing Championships despite having very little sliding seat experience, while Zona was a rower whom Penny got to know through the GB rowing team, and took up skiffing as a result. Jean Wilshee was already expert at both before Penny came on the scene.

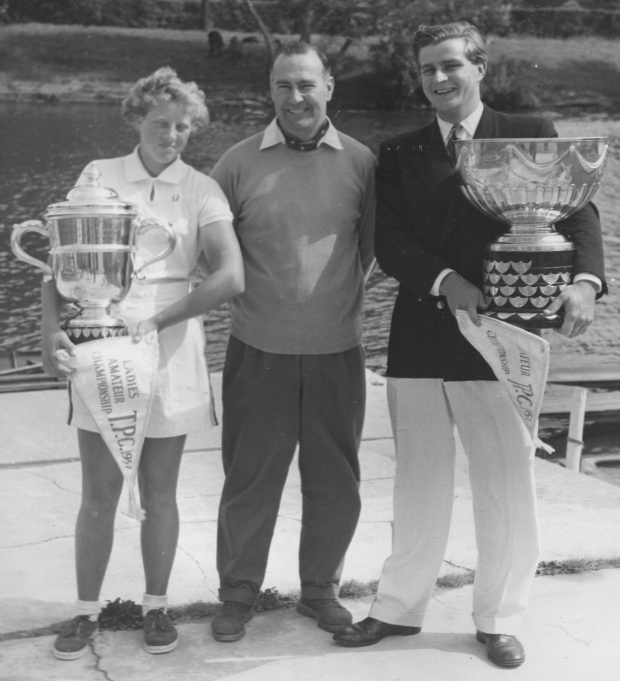

Penny with Nevill Miroy and her clubmate Alan Scott, winners of the Ladies and Gentlemen’s Single Punting Championships 1957. These massive trophies continue to be awarded today. (Photo: Penny Chuter’s personal collection.)

The critical jump from punting and skiffing to rowing came through Penny’s coach at Laleham SPC, Nevill Miroy who had also been a ‘fine boat’ oarsman, winning the Wyfolds at Henley in 1947 (although his club friends would tease him that this had been an ‘easy year’ after the war). His knowledge of the women’s rowing scene did turn out to be a little lacking, though.

After Penny had beaten Jean Wilshee, then the British Sculling Champion, in the Ladies Single Skiff Championship in 1959, Miroy persuaded her to try sliding seat sculling on the grounds that, “If you can beat her in a skiff, there’s no reason why you can’t beat her in a shell sculling boat,” adding the incentive that,”It’s the Rome Olympics next year, so if you can beat her, you can go to that.” As Penny says, “Little did he know!”

“So, in October 1959, I got into a friend’s single sculling boat at Burway RC and sat there shaking, whilst all the men at the club stood watching, waiting for me to fall in. Once they’d lost interest, I took a few tentative strokes,” she remembers.

Miroy was a Quintin BC member as was Frank Harry, who coached United Universities Women’s BC, and so later that autumn he arranged for his young charge to attend tank training sessions with UU. Ann Sayer, one of the UU eight who would go on to represent GB at the 1960 and later Women’s European Rowing Championships, recorded in her training diary that Penny joined them for a midweek evening session:

Unknown Penny at tank – did not like Mr Niroy who did not approve of us – our type of stroke. Said Penny had never been on sliding seat before; if not she made v. good progress.

Shortly after another entry reveals that the eight and Penny trained together on the water:

Sunday morning – alongside Penny. She did rather well; kept up better with us than we should have allowed; annoyed because Miroy on bank.

By the following spring, Penny and Nevill had worked out, of course, that there were no women’s rowing events at the Olympic Games and so international representation meant a trip to the Welsh Harp reservoir at Willesden rather than to Rome.

International sculling career

First win

Even in the 1950s and 1960s, most people’s rowing biographies start with some club or university rowing, some first races at local regattas, generally at novice level, and only after a few years progress to representing GB. Not so Penny’s. Instead she skipped this phase altogether and her first race was at an international regatta in Macon in 1960, to which she traveled on her own (aged 17). And won. Against the French champion, Renée Camu.

She acknowledges that her skiff and punt racing background had set her up to do this; “I think the reason I was able to get into a sliding seat boat in October and race against the French champion the following May was simply that I had rowed across the river to school every day, I’d mucked about in all sorts of boats and I was just a ‘water baby,’ so it wasn’t a strange environment to me and it was just another progression.” All of which is true, although she clearly also put in a lot of work to build on this advantage.

Coaches (lack of)

Nevill Miroy had been a brilliant skiffing and punting coach for Penny, and had given her an excellent grounding in how to move boats, and he was also a good technical coach for sculling but as her sliding seat rowing career developed, she realised that, in the nicest possible way, she was starting outgrow his expertise: his knowledge of training methods, rigging, and international competitive pressure were fairly limited and she needed more advanced training and coaching input. In addition his wife, Barbara, didn’t really want him frequently disappearing off to the Continent to go to international regattas. For both these reasons, Penny needed to develop the knowledge required to manage her own training and racing herself.

So she started doing what would now be called networking and boldly made contacts wherever there was an opportunity. On her very first trip abroad – to a regatta in Macon in 1960 – she found herself on the plane with the Oxford University men and their coach ‘Jumbo’ Edwards. They ignored her on the way out but, on the return journey after she’d won, they opened up, and from then on maintained an ongoing correspondence with Jumbo about the mechanics and biomechanics of the stroke and rigging which were his special areas of expertise. He was known as the ‘scientific coach’. She adds that Jumbo’s experience as a wartime pilot had given him an understanding of aerodynamics which other coaches at the time didn’t have, and he applied this knowledge thoughtfully to rowing in terms of how the blade moves in the water and so on.

“I travelled to some international regattas with Sam MacKenzie [a naturalised Australian who had won the Diamonds at Henley six times from 1956-1962] as he was then GB’s male single sculler. He also gave me some coaching although his technique was most suited to his own physique which was tall with extraordinarily long arms.” In addition Penny received a limited amount of technical coaching and some training programmes from Richard Burnell who was, at the time, one of Britain’s last Olympic rowing gold medalists, having won the doubles at the 1948 Games and was coaching Vivien Roberts and Zona Howard a bit in their double too. Penny says, “Ronnie Howard, Zona’s brother, who had been President of Oxford University BC in 1959 gave me a little help as well but I had no consistent coach throughout my sculling career – I just ‘sponged’ as much information as I could off various people.” These were some of the top experts in their field (although no one really knew anything specific about women’s rowing or racing over 1,000m) but, as Penny puts it, “Whatever men they were coaching were their priority and we just got the titbits really but I was grateful for anything in those days.”

Penny with her 1962 trophy haul from skiffing, punting and rowing. (Photo: Penny Chuter’s personal collection.)

Another of her sources of coaching input came as a result of logistics that had gone wrong; “I loved Amsterdam regatta – I used to go every year although it was always an unlucky course for me. When I first went there with Sam MacKenzie, we arrived late because he always arrived late for everything, and he was supposed to stay at an army barracks and I was supposed to stay at a nunnery which was the accommodation provided for the regatta for all athletes. By this time it was too late to get into either so the President of the regatta and his wife who had been waiting for us at the Bosbaan for hours, asked us if we would like to stay with them for the night. So as a result, every time he or I ever went to Amsterdam we always stayed with them. And because I didn’t have a coach, I would often go out to Amsterdam for a week before or after the regatta and he would coach me, so I got further technical input from him. Technical coaching apart, what was lacking in GB rowing then (for both men and women) was coaches with any knowledge of training theory and I think this is what I needed most.”

Training with United Universities

Penny continued to do some land training and occasional crew boats with the United Universities Women’s BC international group which she joined in 1961, as well as frequently training with the UU double at Henley from 1961-1963, all of which must have provided some welcome motivation and cameraderie even for one so focused. In turn, she sometimes took them skiffing for a bit of fun. Ann Sayer noted many of these sessions in her training diary:

Thursday, 24 November 1960: Gym – included Penny for first time.

Saturday, 7 October 1961: Eight with Penny at 3. Practised some racing starts for Penny’s benefit – not bad at all generally; solid.

Friday, 15 December 1961: Gym: Fanny, me, Penny, Marrian. I went 3x round circuit – annoyed because I had only been round 2x when Penny had finished her 3rd time! But tried to do things thoroughly rather than fast.

Friday, 9 February 1962: Gym: Penny and I round 4x. [Ann did seem to be one of the more disciplined members of UU about land training although to be fair, she did live more centrally than many of the others.]

Wednesday, 21 March 1962: Skiffing: Barbara, PBR [and] cox Penny, Jill, Marrian cox Lester Matthew (LSPC) at Laleham.

Saturday, 14 April 1962: WARA Eights Head. Penny at 3. Won by 44 seconds (though second crew was in a clinker). 10 crews raced. [This is one of the few sweep races Penny ever did herself, though she later coached many GB sweep crews – more on this later!]

Thursday, 17 January 1963: Circuit training – Penny, Ann. First time in new season; attached ourselves to class run for Spartan Ladies AC.

Penny also remembers that in the winter, “We used to go to the old UL tank which was an absolute nightmare at 16 strokes a minute. The oars weighed a ton and with only small holes to allow the water to flow through the blades, it was more like heavy weight lifting.”

Training approach

Reflecting now, after her long coaching career, on the training she did during her international sculling career, Penny feels she didn’t have the right balance in her programme. “When I started with my club coach, who was brought up in a previous generation, it was all distance, distance, distance,” she explains. This was related to the British obsession with what was then called ‘form’ – crews would do long outings at low rates which allowed them to work on the intricacies of technique, but the result was the rowing equivalent of dressage champions rather than racehorses. By the 1960s, though, with no medals having been won at all in rowing at the 1952, 1956 or 1960 Olympics, opinion was beginning to change.

Penny still has a letter that Richard Burnell wrote her around this time, telling her that she was doing too much long-distance training. “I took his advice and started moving more towards much more intensive interval training,” she remembers. Her decision was backed up by current knowledge she gleaned from books about training by successful distance runners including the Australian Herb Elliott and the Brits Gordon Pirie and Derek Ibbotson, because there was very little available at the time specifically about rowing training.

However, what worked in athletics didn’t really translate directly into rowing; “I think we then went over the top with interval training as it was then the ‘in thing’ in athletics, and in the last two years of my five international years, I know now I did too much interval training and virtually burnt myself out. I started off doing perhaps too much long, slow distance and not enough intensive stuff and ended up doing the opposite.”

She continues, “When I started doing more interval training, encouraged by Richard Burnell, it took my body some time to adapt to it. The first phase involving a lot of intensive interval training (IIT) was in May-June 1961 and I got to the point where I simply couldn’t eat enough to maintain my body weight at 11 stone 2 lbs. By the end of June I was 10 stone 10 lb, which was obviously only six pounds lighter, but I had got to the point where I simply couldn’t perform. I know now that I had a bout of mild over-training syndrome and that it was brought about by too much IIT, particularly when this was the first year I had done a lot of it. Equally, I felt ‘fat and stodgy’ if my weight got much over 11 stone 2 lb in the summer. And in 1964, after a winter of heavy weight training, I raced at 11 stone 7 lb and was always concerned about it. There is no doubt that I was physically much stronger, and since muscle weighs more than fat, it was probably to be expected; however, again the lack of a coach with whom to rationalise these things, and with no medial support, it was just another niggling worry in my mind.”

“I discovered later, and this was years and years before lightweight rowing came in, that everyone, male or female, has a critical weight and if you drop below that your performance goes down quite abruptly. Equally I learned that the body simply can’t cope with too much intensive interval training regardless of your racing distance.”

Penny’s water work involved an “unheard of” four outings at weekends, although this required some additional logistics on Sundays because of traditional views at her club:

I can remember there was a big hooha about going out on a Sunday afternoon at Laleham SPC. There was no rowing on a Sunday after 12 o’clock so that was the first law I had to get round – I finished my first training session on a Sunday morning at my parents’ house and left my boat on the front lawn, did the second outing from there, and got the boat back to the club later in the week.

Penny at Laleham SPC in 1961 just before setting off to the Championships in Prague. Note the traditional copper tips on her blades. (Photo: Penny Chuter’s personal collection.)

When asked whether she was tall enough to be a top international rower, Penny says, “I wasn’t tall, but in general you don’t need to be as tall, as a sculler compared to a sweep rower. At the 1976 Olympics – the first that included women’s rowing events – anthropological measurements were taken of all the female rowers and these showed quite clearly that scullers on average didn’t have to be as long-levered as rowers. Today, both rowers and scullers are taller overall and the differences may now be smaller.”

Sculling boats

Once Penny decided to scull seriously in 1960 her parents bought her a new Frank Sims scull costing £95 (her blades were another £15). She named it ‘Loppyluggs’, which she later rather regretted although in her defence, she says, “I was only 17 years old when I chose it!” The story behind the name goes as follows:

I am known for having a really strong ability to focus in on one thing to the point of virtually cutting out the rest of the world and this means that if I am concentrating on something, I often don’t hear when someone speaks to me.

One Sunday morning in January 1960 when I had just taken delivery of my new boat, I had it [on trestles] and was busy recording all my initial rigging measurements, and then making an alteration. Someone came out of the clubhouse and asked me if I wanted a drink – apparently he asked several times and got no reply as I was deep in concentration! In the end he came right up to my ear and yelled, ‘Oi, loppyluggs – clean your ears out.’ Shortly after this I was still trying to find a name for my new boat, and somehow she became ‘Loppyluggs’. The idea was that trying to pronounce such a name in French, German, Czech, etc, might be amusing. As it turned out, this was the case, but at home it later seemed a bit ‘naff’.

When she replaced Loppyluggs with a Stampfli single in 1964 she gave her new boat the more sensible name ‘Tempo’ which is the word Europeans use for stroke rate. There’s only so much mileage can be got out of inducing foreigners to make humorous mis-pronunciations.

Loppyluggs was written off in a trailer accident after being sold to a sculler from Reading RC, and Tempo went back to Stampfli who found her a new home somewhere on the continent.

When she wasn’t rowing…

Penny was a student during her first year as an international sculler in 1960. “I’d decided to stop doing A-levels after one year and take up single sculling and because I’d failed my English Language I went to Brooklands Technical College for a year. Since I only decided to go there at the last minute, the only course left which included English Language was a domestic science course so I took that in order to re-do my English Language O-level. At least it kept me in extra food for the whole of that year’s rowing since I could just walk round the classroom and stick my hand into a tub of sultanas or whatever whenever I was hungry – which was most of the time!”

After that she got a job at the Bank of England (as a filing clerk and eventually as an audio typist, which is a somewhat incongruous image for those who know her on the water). “This was purely to enable me to focus on training,” she says. “There was an international diver who worked there too and a guy from Kingston RC,” she recalls. “They were pretty good employers and would give me extra time off. I can remember racing at Ostend Regatta, getting the midnight ferry home, arriving at Dover at 3am, finding a greasy Pete’s café, driving up to the city, parking my car in a carpark at the top of Cheapside, walking into the Bank of England promptly at 9 o’clock on Monday morning and everyone saying, ‘Had a nice weekend?'”

After she retired from international rowing following the 1964 Women’s European Rowing Championships, Penny trained as a PE teacher – pertinently, her dissertation was on exercise physiology and strength training – and then worked for six years at a school in Sussex where in addition to the normal PE curriculum she introduced all sorts of outdoor activities such as canoeing and sailing.

She then taught for a year at a new comprehensive school in Reading which was brilliantly equipped but which she hated. Although she’d decided by the end of the first term that she wasn’t going to stay there, she knew that she should finish the academic year for the good of her CV – by then, though, events had overtaken her, and she embarked on a journey that would have even more impact on British – and World – rowing than her years as our top woman competitor.

Coaching career

This all started with a bunch of boys at her school in Reading who’d started doing some rowing at their local club and asked if ‘Miss’ would coach them (you have to wonder whether these lads have any idea how their casual request affected the future of British rowing). As a result she decided to do one of the coaching qualifications which the Amateur Rowing Association had recently introduced. At the time, these involved bronze, silver and gold levels which candidates were meant to take in order. She was allowed to skip the Bronze Award because of her international rowing experience, and did the first Silver Award course in late 1972 alongside many others who became really influential coaches across various aspects of rowing in the years ahead including Christine Peer, Phil Rowley, Phil Burgess, Ivan Pratt, Tony Lorrimer and Keith Atkinson. “To be honest, I actually found that I learned very little,” she remembers, “Because although it had been nine-years since I’d finishing rowing internationally, the fact was that I’d HAD to learn so much on my own as a single sculler that I was still abreast of the game. Maybe not ahead of it but certainly not behind it! Also, I’d done anatomy, physiology and biomechanics at college as well as teaching and coaching theory and practice.”

After the course, someone from the ARA contacted her to suggest that she might like to apply for an additional National Coach post that was about to be advertised. “Because I’d already decided I was not going to stay at that school any longer,” she explains, “I thought if nothing else the interview practice’ll do me good and I said, ‘Yes I’ll apply,’ without actually thinking too much about it, and anyway assuming I wouldn’t stand a chance of getting it because I was a woman,” about which she was, of course, entirely wrong.

“The appointment was based on merit”

Readers will no doubt be thinking, “Well, obviously!” but when the Amateur Rowing Association appointed Penny as its third National Coach in early 1973 ahead of male applicants, the very idea of a woman coach was still sufficiently surprising that it had to be emphasised that she was actually the best person for the job and wasn’t just being appointed because she was a woman and they wanted someone to develop women’s rowing.

The ARA had appointed its first National Coach – Bob Janousek – in 1969, and a second – Roger Vincett (from the staff of Emanuel School) – in 1970. Their brief was to create and deliver the Coaching Award Scheme, produce pamphlets on training methods, give lectures and make club visits to develop club coaches at all levels, AND get involved with coaching national crews in the run up to international Championships. Oh, and as if that wasn’t enough, the idea was that each would cover separate parts of the country. “I became very familiar with the M1,” Bob Janousek is quoted as saying in Chris Dodd’s book Pieces of Eight.

By the time Penny became the third member of their team, Bob Janousek was focusing more on coaching the men’s squad so she took over his work on the coach education programme and implemented the Gold level coaching award as Bob had only had time to do the Bronze and Silver levels up to that point. Her job description also evolved, and what happened in the end may not have been what was planned out in advance, if the plan was even clear at the beginning. The June 1973 edition of Rowing reported, “Asked what she thought would be the main duty of her office when she commences in September, with her usual frankness Penny said that at the moment she was uncertain and felt that the ARA was not certain where she would fit into the coaching scene. She hoped to be able to assist in some way to encourage the growth of women’s rowing and its stature but fully expected that… she would be helping to coach men’s crews.” The ARA probably expected this too as her interview had included a question along the lines of, “Would you be able to handle men?” to which she’d replied that as the Head of Boys’ PE at her school had been on long-term sick leave, she’d spent a year teaching boys’ PE, including rugby. She says, laughing, that she added, “‘And after all men are only just grown up boys,’ and I left it at that!”

Despite her extensive racing career in skiffing, punting and sculling, Penny had very little personal experience in crews larger than a double skiff, or of sweep oar rowing. This, however, was the least of her concerns when she started coaching, because of how she approached the task. “I don’t know how, but I have a feel for water,” she explains. “And whilst you can take every boat class and say it has to be coached slightly differently, it’s a bit like when I retired and started taking an interest in Cornish pilot gigs… they are bigger, heavier boats, but what fascinated me… was just really, from an academic point of view HOW can you get the best out of these boats? I’m used to heavy boats but only in a skiffing [sculling action] context, but it didn’t take me that long to sort it all out and you’ve just got to accept that the water is going past the boat at different speeds and that’s the thing that mainly makes the difference. When I started coaching in the 1970s I was actually quite confident because I felt who else in GB has done any coaching of women? Very few, and of those, very little.”

Coaching GB women

Penny’s subsequent work running the GB Women’s Squad for the World Championships in 1974 and 1975, and the 1976 Olympics, and then coaching the Beryl Crockford/Lin Clark pair in 1977 and 1978 is described in detail in the year-by-year reports here at Rowing Story.

Coaching in 1975. (Photo: Penny Chuter’s personal collection.)

A profile of her by Dave Collingwood that appeared in Rowing magazine just before the 1976 Olympics included the bizarre, but also pretty much spot-on conclusion that, “Her impact on women’s rowing has been similar to that of yeast in a beer vat.” He stretched the analogy further – possibly too far, although he was at least seeking to be complimentary – continuing, “The [squad] is not yet CAMRA standard but it’s becoming palatable.”

Other GB coaching

After the 1976 Olympics, Penny stopped being Women’s Chief Coach and took on the management of the Junior Men instead. Her decision to move away from running the women’s squad was deliberate because she felt that the women’s squad had enough of a struggle to get what it needed without it’s chief advocate also having to overcome hurdles because she was a woman. With a man in charge, she explained, at least he would only be fighting on one front not two.

On returning from a short holiday following the Junior World Championships in 1978, Penny got what she describes as her “big break.” Jim Clark and John Roberts, who had been silver medalists in the GB men’s coxless pair in 1977, were struggling to get selected for 1978, and at that point had no coach after a winter of preparation marred by injury and changes of coach. Penny had been coaching Lin Clark and Beryl Mitchell in the women’s pair but they were not selected that year and Lin had suggested to her husband Jim that they should try her out since she was a good coach and available at that time.

Penny described the period she spent coaching them through to the Worlds in Karapiro, New Zealand in November 1978, as the best of her whole coaching career, as she was able to concentrate on coaching without having to “charge round the country” doing Coaching Award Scheme work or produce education materials like her popular National Coaching Journal. “It was absolutely great,” she remembers, smiling, “And I was free from the pressure of ARA politics.”

Having made some fundamental changes to their technique by moving them away from the extreme leg compression the rest of the men’s squad was using at the time and adding more body swing forwards – fundamentally what’s considered ‘standard’ today – they went on to win another silver. At around 23’30” into the coverage of the Roberts/Clark pair’s final the Kiwi commentator remarks that, “A new coach this year they’ve got, and she’s a woman too!” which seems to today’s listener just to be a stereotypical example of antipodean sexism but, although the guy might have put it better, he was also only following good journalistic practice in highlighting the unusual – this was, in fact, the first time a women had coached a senior men’s crew at a World Championships.

What comes over as utterly patronising to the 21st century audience was also commonplace at the time too; an article in the Daily Mail at the time by Roy Moore was headlined “Penny’s in charge as Clark battles for gold” and included the extraordinary lines, “Jim Clark and John Roberts have a woman to thank for giving them the chance of a gold for Britain in the coxless pairs at the World Championships in New Zealand,” as well as, “And much of the credit goes to Penny Chuter, a 36-year old blonde from Surrey.”

John Roberts (left), Penny Chuter and Jim Clark celebrate their silver medal at the World Rowing Championships 1978. (Photo © Don Somner.)

With her ability to coach men proven, Penny was then appointed Senior National Coach with responsibility for the GB men’s squad and was able to hand over much of her coach education work although she still had to still lecture at coaching courses.

Two critical technical changes

One of her main aims in this role was to move the whole squad away from the “extreme” version of Karl Adam compressed technique which Bob Janousek had taught, and which Penny believed led to too much lactic acid build up which had a negative effect on performance over the last part of a 2,000m race. “You could see it in the TV coverage of the final in Montreal in 1976,” she explains. “They were so compressed that the stern edge of their seats were cutting into their calves at the catch – no forward reach at all.” She’s quick to emphasise, however, that she never sought to undermine him on this point and publicly, as part of the coach education programme, always supported this technique.

Working with Bob Janousek

Penny and Bob Janousek had great mutual respect although they didn’t work particularly closely together in the three years they overlapped at the ARA because that wasn’t in their remits. As a paid coach, Bob found himself struggling against some of the structures of the time where he was answerable to or at least meant to work with volunteer committees, some of whose members were perceived to feel that they were highly important just because they were on a committee, and also could do what they wanted because, as volunteers, they couldn’t be ‘sacked’.

As Penny remembers, Bob said to her when she started, “‘Look, I’ve got my own problems as a Czech but I will never stand in your way and I will always support you.’ However, in practical terms, although he was a mentor in many respects but I didn’t necessarily see a lot of him.”

Bob Janousek left the ARA to start his boatbuilding business after the Montreal Olympics in 1976.

As an alternative to extreme compressed technique, “I introduced something that I called the ‘reach technique’ because you get your body over,” she explains. “But I was finding even by the time I left [in 1994] that there were still people who had gone through the Coaching Award Scheme still teaching it – in public schools mainly, schoolmasters who’d been there for whatever years, still coaching this complete extreme.”

Her other major technical innovation was to standardise how Britain sculled in terms of which hand led, so that all scullers presenting for trials had the same lead hand. Despite being a straight two-way choice it was not made by the flip of a coin, but was based both on research and sound logic. In the Autumn of 1976 she went to as many sculling heads as she could and noted the numbers of scullers leading with each hand. To this she added the fact that she felt the ‘underneath’ hand has a more technically difficult job drawing up at the finish of the drive phase, and as more people are right handed, she considered it would be beneficial if the hand that was more dexterous for the majority took this role. And that’s how Britain took to sculling left in front of right – even though our top sculling crew at the time – Mike Hart and Chris Baillieu – sculled right in front of left.

Penny’s third silver

In 1981 Penny ‘got’ yet another silver medal to add to her own European Championships one in 1962 and the one that she had coached John Roberts and Jim Clark to in 1978, this time with the men’s eight.

What’s in a name?

During the 1981 season Penny was often referred to jokingly as ‘Rigger Mortis’ by the men’s squad because, “I seemed to do more rigging that anyone else,” she remembers, but adds that there were two reasons for this. “I was fascinated by rigging because I believe rigging is there to support the individual athletes and the crew overall. I [always] set up every single rigger for lateral pitch and stern pitch – I think it’s lazy not to use both because you can use less pitch if you use a combination, and pitch is inefficient so the less pitch you can encourage a rower to row with the better. But the name was also because in 1981 when I was coaching the men’s eight, we had a training camp in Varese where it was stinking hot and our Carbocraft eight’s riggers had black plastic clamps to support the pin angle adjustment. As they were black and plastic they absorbed the heat and softened in the sun and wouldn’t hold the pin at the angle set. We were doing ‘fine tuning’ which involved quite a lot of flat out speed bursts at rate 40. After only a couple of these we’d have to return to the landing stage and I’d have to reset them all again. I spent the whole of that pre-World Championship training camp rigging that eight – thank goodness it was cooler when we got to the Championships in Munich!”

Penny in 1980 at Thorpe Park. (Photo © John Shore.)

Penny would sometimes solve rigging issues by getting in the boat when she was coaching the men’s squad. “Often athletes complain that something is wrong but can’t identify what. If I couldn’t see a problem, then I would just get into the boat to ‘feel it’ for myself and could then often identify the issue.”

Further coaching appointments

After that, though, as most good managers know, you often need to resist ‘doing’ when you should be ‘managing’, and so when Penny became Director of Coaching for all the GB rowing teams in 1982 – the first woman to hold that position in any national rowing federation – she no longer took personal responsibility for the coaching of specific crews, although she regularly joined each senior squad coach to monitor their crew’s progress. She admitted to Christopher Dodd in an article for the October 1989 issue of Regatta magazine that this made her feel thoroughly “jealous” as she gave Chief Coach Mike Spracklen “everything I wanted to give myself” in terms of the pick of the best athletes to coach for the Olympics in 1984 and 1988, but there couldn’t be a better proof that she was always trying to do the best thing for the team’s results rather than pleasing herself, a point which some athletes didn’t – and possibly still don’t – appreciate or believe.

Penny (left) and Mike Spracklen coaching before the Seoul Olympics. (Photo © Fiona Johnston.)

She was appointed Director of International Rowing in 1986, with responsibility for management and finance as well as the selection and all performance aspects of all squads, which she did until 1990 when she was moved back into coach education as Principle National Coach, a change she ‘was told was a ‘sideways’ move although this was an interpretations she didn’t at all share.

After 20 years at the ARA and, in her own words, “burnt out” by the volume and stress of work, she left in 1994 to become the Chief Coach/Development Coach for Oxford University Boat Club. In 1997 she went to work for Sport England where she remained until she retired in 2002 at the early age of 60.

Successes and challenges in Penny’s management years

British rowing turned a corner at the 1984 Olympics when the men’s coxed four won GB’s first Olympic rowing gold medal in 36 years. Yet despite many successes, her time as Director of Coaching and then Director of International Rowing was dogged with three major challenges: a lack of money, a massive workload and various controversies about the changes she was seeking to implement with regards the GB squads’ structure, management, training and selection procedures. All three were, of course, closely interlinked.

Like many similar sports – especially those that can’t get revenues from entry fees to a stadium – the ARA has struggled for money for much of its existence. However, it had several particular financial crises which are documented in its own Almanack, often exacerbated by changes in the amounts and ways that external funding bodies allocated grants. One of these led to a lot of the squad’s boats being sold off after the 1984 Olympics to plug a desperate financial hole.

Penny describes the situation that prevailed throughout most of the 1980s:

The squad system was so weak because of lack of money, lack of facilities, lack of boats. The funding system with the Sports Council changed after 1988… and there was just less and less money, and when it was going to arrive and if it was going to arrive was less and less predictable so you couldn’t plan. I was a forward planner, although I say it myself, one of my strengths was that I was a planner down to every detail, but you can’t plan if you don’t have the money or know how much it’s going to be or when you’re going to get it. And if the funding starts on 1 April by which time you’ve already started that year’s programme the previous September and you’re having to decide what regattas you’re going to go to, book accommodation, book flights, and you haven’t got any money… it was just non-viable… In the end, if you want to criticise me, I’d created a system for the 21st Century but we didn’t have the funding to run it.

Throughout her time as Director of International Rowing she made sure that the women’s squad got a fair deal compared to the men and that all of the women’s Sport England grants were spent exclusively on the women.

One of her major changes during this time was to the way selection was done, finally moving GB rowing away from having Selection Boards who passed judgement on whether an individual crew (albeit one formed from members of the national squad) would be sent to a Championships.

There were two main reasons why the Selection Board approach was no longer appropriate. First, she says, “In the small rowing community it was becoming impossible to find people who had the knowledge and experience required to be Selectors and yet weren’t biased due to having relatives being selected or athletes from their clubs for selection.”

Second, the whole concept was increasingly unnecessary. “Once you have a group of coaches with a chief coach running a recruitment, preparation, training and assessment system then the actual selection of who’s in the boat and if the boat should go is just the end of that natural process. The input of the coaches throughout the process is extremely important and even if some of them are biased, if you’ve got three or four of them working together under a Director of International Rowing who’s chairing the meeting, the biases of one coach are generally balanced by those of another.”

While this all sounds fine in theory, the practicalities of disbanding the Selection Boards proved harder. “They wouldn’t accepted it,” Penny explains. “Selection boards are very important, powerful people, so it’s not easy to sack them! The compromise for the 1984 Olympics was a combined Selection Board and that was more of a disaster because – I think – there were seven of them and when they were talking about the men’s team, there was perhaps two who knew about the men’s team and five who knew about the juniors or the women, and so… the majority of the panel was not an expert on the particular squad that was being selected. So that didn’t work at all.”

“After all that in 1985 or 1986 I became the chief selector which in effect… I tried to operate it so that I would sit with the junior coaches or the men’s coaches or the women’s coaches and we’d reach decisions. But the bottom line was that because it wasn’t a panel, the outcomes were published my name so I was seen as the ‘big baddie’, which in retrospect probably wasn’t a good idea because it wasn’t just me making the decisions.”

The mountain of admin involved in running the squad included obvious things like arranging all the trips abroad to regattas and training camps for which the details may be mundane but are nevertheless essential – for example, Penny remembers arriving at an airport one with a group, only to find that there had been no transport booked to get them to their ultimate destination. Sports Aid Foundation grant applications had to be made for all athletes, and the simple number of these increased when the women’s lightweight squad was added from 1985 too.

She is in no doubt about the link between structure, management, training methodology, selection procedures and success, though – the 1984 Olympic gold was a result, she says, of, “A system that at last enabled us to put all (without exception) of our best athletes in one boat.”

The structures Penny implemented were certainly unpopular with some at the time, but when National Lottery funding was first made available in 1997, rowing was one of the first sports to get it because of the governance that was already in place. “We didn’t have to jump through many hoops [compared with other sports],” Penny explains. “As soon as you had funding and you could pay full time coaches and you could offer boats and facilities and not have to ask the athletes to make a contribution to every international regatta they went to.”

A two-page interview with her that was published in the November 1989 issue of Rowing, shortly before she left the British International Rowing Office, describes in agonising detail why the system was failing for lack of money – how coaches wouldn’t work in the squad because there was no one to do the admin and logistics work and how tasks that used to be done by volunteers no longer were because volunteers understandably didn’t have time for increasingly onerous roles – but ends with the plea to the ARA, “Keep this most successful system going.” Fortunately, it did.

Colour coding

From rigging to grant applications to travel arrangements, it’s clear that Penny was a details and this is possibly never better demonstrated than in the colour coding system which she introduced for the different squads that covered both paperwork and riggers (which were marked with tape).

Women – pink paper, red tape

Men – blue

Juniors – green

Lightweight men – yellow

Lightweight women – orangeSimple, but you can see how much confusion it avoided!

Changing things at FISA

In 1983 Penny joined the women’s commission of international rowing’s governing body and played a key role in the distance for international senior women’s rowing being extended from 1,000m to 2,000m and for junior women from 1,000m to 1,500m, quads moving from coxed to coxless, and events being introduced for women’s lightweights at their current weight limits in 1985.

She presented a substantial paper to the FISA Coaches’ Conference in October 1983 that pulled together scientific research which supported moving both junior and senior women away from 1,000m racing. As she explained in its introduction:

The introduction of events for women over 1,000m and junior boys over 1,500m [which they did until 1989] was clearly influenced by one basic misconception – that is, that racing over a shorter distances is easier and less stressful and that therefore women – being the weaker sex – and juniors – being immature adults – should therefore race over shorter, ‘easier’ distances than the men.

However, “current knowledge” at the time had revealed that races of about three to four minutes are actually, “The most stressful upon the human organism,” and can be classified as requiring “maximal performance”, predominantly using the lactic acid anaerobic energy system. She went on, “Since maximal performance cannot be endured for long, the body is forced to moderate to a sub-maximal intensity for the longer time periods, such that longer distances are less stressful on the heart muscle… It seems we have chosen [for women] a maximal performance distance which is the most demanding physiologically.”

She added that “The very high performance intensity [involved in 1,000m racing] also requires a high level of explosive strength and power, together with a physique capable of generating such power.” What goes with this is that anyone taking anabolic steroids would have a disproportionate advantage in a 1,000m rowing race compared with a 2,000m race that required strength endurance.

Her paper concludes by observing that changing the race distance would lead to training programmes being adapted accordingly with the result that would be no physiological reason why women and juniors would not be eminently capable of racing longer distances.

Penny moved to FISA’s Competition Commission in 1985 – yet another female first for her as this was the first time a woman was appointed to a FISA Commission other than the Women’s Commission. She served on it till 2006 in various roles including as a member of the new Seeding Panel for World Championships and Olympic Games and the new Fairness Panel which started to operate at all World Cup and World Championships events to guide FISA as to when conditions were unfair and/or unrowable, a subject close to her heart as a lack of these almost certainly cost her medals when she was competing as a single sculler.

Awards and recognition

Penny was awarded the OBE in 1989 for services to British rowing after nomination by members of the GB rowing team who were unimpressed that the heads of other successful sports had received honours after the 1988 Seoul Olympics but the Director of International Rowing hadn’t and yet our team had got their second consecutive gold medal.

She was given the ARA Medal of Honour in 2006 when she also received a Distinguished Service Medal from FISA, as well as numerous other less high-profile awards.

Retirement

Penny retired to live in Cornwall where she actively pursues her love of sailing and has also returned to her fixed seat roots by taking up Cornish pilot gig rowing as well. She finally given up competing in these 2014 due to a bad back caused by a weight lifting injury sustained in 1964. She now coaches at Flushing and Mylor Pilot Gig Club and her women’s crew won a silver medal [another one! – Ed.] at the World Pilot Gig Championships in 2016. She maintains her links to the river which so defined her life in the name she has given her house – Thames Cottage.

In 2022, aged 80, Penny added another type of international rowing representation to her lengthy palmares; coxing! This was at the World Rowing Coastal Championships (for club crews) in Pembrokeshire, where she coxed the Carrick RC women’s quad she’d been coaching to a respectable 13th place overall.

© Helena Smalman-Smith, 2017.