| Years | 1986 World Championships (4+ 8th, 8o 6th) 1987 World Championships (8o 9th) 1988 Olympic Games (4+ 6th) 1989 World Championships (4- 8th) 1990 World Championships (2- 5th) 1992 Olympic Games (8o 7th) |

| Clubs | Trinity Hall BC, Cambridge University Women’s BC, Thames RC, Tideway Scullers’ School, Norwich RC |

| Height | 5’11¼” or 181cm |

| Racing weight | 10 stone 1 lb or 64kg |

| Born | 1959 |

The photo at the top of this page shows Kate at 2 (second from the left) training in the GB coxed four shortly before the 1988 Olympic Games, and is from Fiona Johnston’s personal collection.

Getting into rowing

Kate took up rowing in 1978 when she was in her second year at Cambridge but for quite a long time her interest in it exceeded the sport’s enthusiasm for her. “I was a VERY slow learner,” she remembers. “In fact, my college boat club asked me if I wouldn’t mind giving up because I was so bad. I was pretty un-coordinated so I couldn’t keep in time, and I had – I still have, actually – a very strange style, but nowadays at least the bit in the water is a lot better than the bit you can see!”

Kate rowing at bow for her college four. (Photo: Kate Grose’s personal collection.)

After rowing for her college as an undergraduate, Kate was selected for the Blue Boat in 1984 when she was doing a postgraduate architecture diploma following a year working abroad. But right up until the Boat Race itself her place remained in question because of her technique. When international coach Mike Spracklen came to coach the crew for the final two weeks, Kate remembers him telling Nonie Ray, the CUWBC President, “You’ve got to drop her, I know it’s only 10 days to the boat race but she’s an accident waiting to happen. She WILL catch a crab and ruin it for everyone,” but Nonie’s reply was, “We’ve tried really hard to drop her, we’ve seat raced her to within an inch of her life, so it’s not going to happen.” “Mike said to me, ‘I’ve never seen anyone row that badly at that level,'” she recalls. “He wasn’t being nasty, he was just worried for the crew. And then when I was rowing at Lucerne in 1986, my first international year, he came up to me again and said, “You HAVE improved a bit – not much, but a bit!’

For the record, Cambridge won, and no crabs were caught.

Kate at 2 in the 1984 Cambridge Women’s Blue Boat. (Photo© John Shore.)

That summer, Kate rowed in a similar CUWBC crew which won the gold medal at the National Championships, setting an ‘unbeatable’ record in the process because that was the only year when the women’s events were raced over 1,500m as a transition from the old international distance of 1,000m to 2,000m which was used from 1985 onwards.

International career

Kate moved to London after completing her studies at Cambridge in the summer of 1984 with no intention of ever rowing again. “As far as I was concerned it was a great thing to have done at university but then you move on,” she says. Despite this she agreed to go along to Thames RC for an outing with a Cambridge friend who was rowing there, “But it took me so long to get there from where I was working, I thought ‘Never again!’,” she remembers. However, she was lured back by other Cambridge friends in early 1985. “We thought that Thames would be welcoming because we’d showed we were quite good at Nat Champs, but they were unbelievably unwelcoming apart from Pauline Rayner, who had been an international in 1960, and thought we were the best thing – she was LOVELY to us. In retrospect, I think the other girls thought we might grab their seats, so we were stuck in a four and nobody would row with us, but then Pauline Rayner and three of her veteran friends asked us if we would jump into an eight with them for the Women’ Head, and we beat the Thames first eight by four seconds. They were SO cross! So instead of making us popular it made us even more unpopular.”

After a successful summer racing with her four, she rang the Amateur Rowing Association in early 1986 and asked if she could take part in the next squad trials. It turned out, however, that her reputation for having an unusual technique preceded her. “They asked me my name and when I told them, said, ‘No, we know all about you, no hope,'” she remembers. “I had very definitely been blackballed, so I didn’t go but my housemate Debbie Flewin did go and after the first day she came home and said that someone had got injured so she’d told the coaches that she had a friend who could come to make up the numbers but didn’t tell them my name because she knew I wouldn’t be allowed to go. So I just turned up and nobody knew who I was and for the first time ever I raced in a pair. We raced up and down at Thorpe Park in pairs all day and at the end of it the Director of Coaching, Penny Chuter, said, ‘You can stay on if you like, but I don’t know your name. I think you’re either Debbie Flewin or you might be Kate Grose but I find it hard to believe you’re Kate Grose so I think you must be Debbie Flewin!’ Anyway, I got to stay on to do the next round, but if that hadn’t happened I never would have got in.”

“I generally always did well at seat racing, partly because nobody expected me to and actually seat racing is one of those things where if you have a psychological advantage you can do well,” she reflects. “And I loved seat racing because it was the only way I ever got selected for anything. I was always dropped from the coaching launch.”

She was initially selected for the eight, which was a doubled up crew comprising the coxed four, the pair and two others (of whom she was one), and raced at the Commonwealth Games. After this she was given a place in the four as well, and raced in both crews at the World Championships.

Kate left Thames after the 1986 Worlds. “The rest of the squad tehre had given us a pretty low-class welcome, but more importantly I’d realised that Beryl Crockford and Lin Clark, who had won gold in the lightweight double scull in 1985, having previously raced openweight [prior to the introduction of lightweight events that year], were so much better than us openweights, and I was embarrassed that I didn’t know how to scull when all the continentals I was racing did, so I thought I’ve got to learn. So I tootled along to Tideway Scullers and asked Alec Hodges to teach me to scull and then Bill Barry took me on. I really loved sculling and although I was never a good sculler, I was a jolly good basher. I could bash with the best of them!”

She went on to represent GB in the eight in 1987, and the coxed four in 1988 which pulled out a stupendous performance in the repechage to become the first GB women’s crew to race into an Olympic final ‘when everyone was there’ (there had been boycotts at the two previous Olympic Games, by the Eastern bloc in in 1984 and by the USA and Canada in 1980 when GB crews had been in finals, and neither British women’s crew made the final at the first Olympics to include women’s events in 1976).

In 1989 the same crew raced at the World Championships (although coxless, following a change in the roster of events), but did less well than they had the previous year. In 1990, Kate rowed in the pair with Jo Gough. “We were the second boat, I think,” she says. “But it just clicked.” Their fifth place that year was not only the openweight team’s highest placing at those Championships but her best ever international result.

Kate and Jo continued rowing together in the 1991 season, but did so outside the squad which, she says, “In retrospect, was a really foolish thing to do, and it didn’t make us popular [with the chief coach] but, to be honest, I was fed up with the squad system by then.” In the end the issue became moot as she developed a glandular fever-like illness and was told by the British Olympic Medical Centre doctor to stop rowing for the rest of the season.

She was fully recovered for 1992 and won a place in the eight which raced throughout the early season regattas. This was the third of the three GB crews, behind the pair and the four, and Kate’s memory is that Chief Coach Bob Michaels made it “as clear as he possibly could” that the eight was unlikely to be selected to go to the Games. But, she says, “The eight flew. It absolutely flew. Not to begin with because we all sort of turned up and looked at each other and it was little and large and was a joke really. We all kind of giggled about it because we knew that we’d virtually been told, ‘You know you can keep training if you like, girls, pat on the back, but frankly you’re a bunch of has-beens or people who are too young to even consider,’ but the eight just got better and better and better.”

After achieving an excellent fourth place at Lucerne regatta, the last event before the Olympic Games in Barcelona, the three crews were rearranged, partly to accommodate the fact that Fiona Freckleton, who had been in the pair, had been diagnosed with glandular fever, but also because the eight had proved to be competitive whilst the four’s results had not been as good. Kate remained in the eight, but four other members of it were changed. She was furious, and the new crew did not gel at all, eventually failing to make the final by four seconds. “It was just humiliating, the most humiliating experience of my life because everybody expected us to be quite good and we were absolute rubbish,” she says.

Full accounts of Kate’s years in the GB squad can be read here:

1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1992

Following her experience in 1992, Kate decided to stop rowing internationally. “[Before the crew changes happened] I had thought that I would try and do another Olympiad. I’d have been 37 and I figured that would just about be doable, particularly for women. I was still pretty much top of the ergo pile, despite being quite light and I’d never had any injuries. Then after Barcelona my first reaction was that I wasn’t going to go through four years more of training to be messed about at the last minute to this extent, which was so beyond our control, although when Bob resigned I did waver, and nearly changed my mind when Bill Mason was put in charge as I thought he was a really good coach, but actually I’m glad I didn’t because Atlanta was another disaster in a different way.”

Kate at the opening ceremony for the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul. (Photo © Fiona Land.)

Kate qualified for the first open Women’s Single Sculls event at Henley Royal Regatta in 1993, but lost in the first round.

In 1994 Kate agreed to do a pair for the summer with Tish Reid, who was trying to make a comeback after a dreadful back injury. “I wasn’t interested in making a comeback,” Kate says, “But we’d done a successful pair back in 1986 so we gave it a go and we were having a lot of fun, really enjoying it, pairing out of Lea RC, although we weren’t getting out very much, to be honest, and she was training harder than I was.”

They raced and won at one of the various events which took place at Docklands back then, after which they were told that the regatta had been the Commonwealth selection regattta, which they hadn’t known, and as they’d won, would they like to do it as the main GB squad wasn’t going to be sent.

“Our initial response was, ‘No thanks, we’ve already done a Commonwealth Games,'” Kate explains, “But then they said, ‘Oh go on,’ and we said, ‘No,’ again, And then Eddie, Tish’s coach, said ‘Well, why not because it would be another race for you and you could have quite a fun season?,’ so we said, ‘Yes please.’ Then they told us that we’d have to pay £1,000 each because it was in Canada, and we said, ‘Oh, no, we’ve gone off that idea.’ But we had a few weeks so Eddie encouraged us to see if we could get some sponsorship and we managed to raise the money quite easily, or we were getting there, so we rang the ARA up and said, ‘Yes, we would like to do it,’ because they’d given us a bit of time before they’d go back to the second-placed crew, but it had been quite a long behind so they weren’t desperately keen on that option. At this point it all got just hilariously ridiculous because we were then told, ‘We’ve discovered that at the selection regatta you didn’t realise it was the selection regatta, so you weren’t under as much psychological pressure as the others so you’ve got to race them pair again.’ We politely pointed out how far behind us they’d been but were told that had nothing to do with it because they were so nervous and it was so important to them. We said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding,’ and they said, ‘No, that’s what you’ve got to do.’ And again Eddie said, ‘More racing, great, go out and do it!'”

“So we turned up at the docks on a very, very, windy day, massive cross wind,” she continues. “There were just the two of us to race this other poor pair, and I said to Tish, ‘What do you think about these conditions?,’ and she said, ‘Same as you, they’re not going to call us back!’ So we sat on the start and they couldn’t get us straight, but we were doing a much better job of getting straight than the other pair because we had about a zillion times more experience, and we did jump it and they didn’t call us back. We beat them by a load more than we had the first time, and felt really quite guilty afterwards.”

They then went to Paris regatta for some extra practice. “I think we were actually level with Miriam Batten and Jo Turvey [the GB pair at the Worlds that year] to half way!”

They won the silver medal at the Commonwealth Games, behind Australia. “It was a straight final and we didn’t race as well as we could have done. We felt that we could have been a bit closer. I don’t think we could have won but we could have got a bit closer but it was quite a nice end, because after Barcelona which was awful, it left us with a much better feel good factor about the whole thing.”

Later rowing

After 1994 Kate only sculled in her single for the next few years, particularly as she was mainly based in Norfolk, working from offices there and in London. In 1999 she brought her boat back to Tideway Scullers and realised that their women’s squad was going through rather a slump so decided to join in with them to see if she could help by sharing her experience. She competed three times at Henley Royal Regatta in TSS eights.

-

A contemporary-style portrait which perfectly captures Kate, painted by her artist crewmate Flo in 2019. (© Fiona Land.)

She continues to race regularly, often showing much, much younger crews a thing or two at the Head of the River Fours because it really is just about what the blade does in the water.

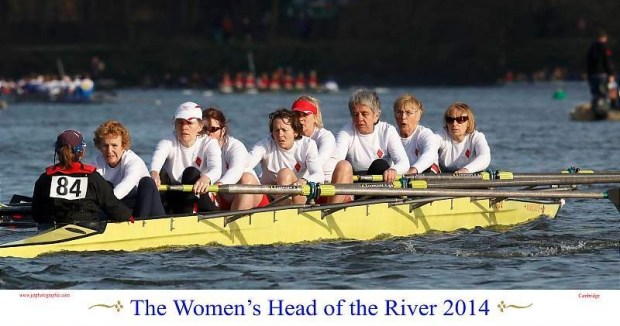

In 2014, she raced with Pauline Rayner again at the Women’s Head of the River Race, celebrating Pauline’s 60th anniversary of first competing in the event in 1954.

Kate at 5 racing with Pauline Rayner at 2. The author is coxing. (Photo © JET Photographic.)

© Helena Smalman-Smith, 2019.