Rowing at the 1992 Olympic Games took place at Banyoles, about 100km from the main venues in Barcelona, from 27 July to 2 August. At this the fifth Games to include women’s events there were 67 women’s entries from 25 countries.

This was by far the highest entry in an Olympic regatta to date, and was typical of these Games as a whole, which reeled under far more entries than had been expected (approximately 18,000 athletes compared with a planned 10,000), possibly partly because they were the first in Europe for 20 years – with the result that rowing, like other sports, was given a quota of participants for 1996 onwards, meaning that countries nowadays have to qualify boats before they can take part.

With the break-up of the Soviet Union ongoing, most athletes who would previously have competed for the USSR represented a ‘Unified Team’, which paraded under the Olympic flag, although Unified Team rowing crews still had the red strip and blades that the USSR had always used. Latvia and Lithuania competed as themselves for the first time in women’s rowing.

The World Rowing Championships for the lightweight events took place in Montreal, Canada from 12-16 August in a combined regatta with the World Rowing Junior Championships. 35 women’s lightweight crews competed from 23 countries, which was one down on the number of crews that raced the previous year but still extremely healthy given that the event was in North America.

Coaching and squad formation

Bob Michaels was in charge of the openweight women for the third year in a row which was unusual continuity for the women’s squad where chief coaches mostly only stayed for a year or occasionally two. While this was a plus point in some ways, many of the squad didn’t feel that it turned out well. His mantra for the year was “Building on Vienna”, referring to the fact that the coxless pair of Miriam Batten and Fiona Freckleton had won the first British women’s openweight sweep world medal at the World Championships in Vienna the previous year, and the coxless four had come fifth – the best placing for a British women’s openweight four since women’s events were first included in the Worlds in 1974. Although there was great respect for the achievements of these six women, at least some of those who were not part of this group felt that these six were protected in a two-tier ‘them and us’ system, and took to referring to them with some envy as the ‘kebabs d’or’, a phrase reflecting their perceived status as ‘golden girls’ that also referenced Bob’s Greek nationality (‘Bob Michaels’ being an anglicised version of his name). Another point of view is that the Vienna six had proved themselves on the World stage. Either way, though, this set the squad up in such a way that it was almost impossible to combine the two groups when Bob eventually decided that they should form an eight together.

Other coaches who worked with the openweight women included Pete Proudley, who had coached Miriam Batten on and off since she was a student at Southampton University; CD Riches (Bob’s boss at Westminster School BC); Ron Needs, who coached the ‘private army’ double of Ali Gill and Annabel Eyres; Jon Tompkins, who had coached the late-formed GB four in 1990; and Eddie Wells, who was single sculler Tish Reid’s personal coach at Lea RC.

The December 1991 issue of Rowing magazine reported that, “Michaels believes that squad oarswomen in the past have been let down by their coaches who were either good coaches who failed to function or second-rate coaches who shouldn’t have been there in the first place,” [not that there was ever another option when this was the case – Ed.]. The piece also explained that, “Michaels has already earmarked the pair and the coxless four as his top boats. He also hopes to produce a medal class eight but is not sure there will be enough depth in the squad to prevent doubling up.” The eight in 1991 had been doubled up, which Bob described as “a qualified success” in his 1992 strategy document, adding “The issue of doubling up will be considered after the formation of the small boats which will have priority.”

The main openweight squad trained in Hammersmith during the week and Henley at weekends. Looking back on the year afterwards, many felt that the benefit of good water at Henley was offset by the amount of travelling, boat loading and rigging involved, although they pointed out that the latter could have been reduced by leaving the small boats in London and basing the eight and fours boats at Henley.

Another criticism of this squad’s organisation made in the post-season wash up report was that different combinations were not experimented with in training, which made it harder to put new crews together at the last minute when late changes were made.

Bill Mason became Chief Coach for the lightweight women, replacing David Lister who had moved to the openweight men’s coaching team. Bill’s ‘day job’ was running Imperial College’s rowing. He coached the four, assisted by Tony Reynolds who had also supported David in 1991. Rosie Mayglothling coached the double of Helen Mangan and Trisha Corless, and single sculler Sue Key, who often trained with the openweight double, was coached by Ron Needs.

In contrast with Bob Michael’s approach of “building on Vienna,” Bill put all of the contenders back into the melting pot. “We were very clearly told that just because you’ve been successful, you’re not on a pedestal, you’ve got to prove your worth again,” 1991 silver medallist Alison ‘Wilma’ Brownless remembers.

Funding

In addition to Sports Council funding for all the British International Rowing schemes, Hill Samuel bank sponsored the women’s squad to the tune of £18,000, and Miriam Batten’s employer, Debenhams, made a small financial contribution towards her costs. Sue Key received some support from the Thames [RC] Charitable Trust.

The squad strategy document for the Olympic group that year stated, “It is unlikely that athletes still being considered after January 1992 will be able to earn their living for longer than a part-time basis (10am-4pm) and it is likely even that will have to stop after March 1992. This, of course, meant that there was a hidden cost to the rowers in terms of loss of earnings.

SAF grants of £5,000 a year were awarded to the top athletes who were continuing from the previous year. To put this amount into context, a teacher’s starting salary at this time was £11,184 before tax, while unemployment benefit was approximately £2,241 a year. While the logic of only funding the top, proven athletes is understandable, it also contributed to the two-tier setup.

As the sweep squad members were expected to train in Hammersmith, they all needed to live at least within reach of central London, and they also had to pay contributions towards the cost of various training camps and regattas amounting to £480. Everyone had a different way of balancing the competing demands of needing to work to support themselves and pay for their rowing whilst also having enough time to do the volume of training required to be competitive at this level. These necessarily individual arrangements meant that some people could train during the day but others couldn’t, which probably didn’t help the squad to feel like a single, cohesive group. Debenhams allowed Miriam to go part time; Hillier Parker for whom Tish Reid worked full time as a chartered surveyor gave her extended leave to compete at the Games and also bought her the Empacher boat she raced in; Annabel Eyres and Ali Gill had started the rowing t-shirt company Rock the Boat to support themselves while they trained full time; and Kate Grose, who is an architect, was also working for herself, thinking that this would give her flexibility in her schedule, although she had rapidly found out that this meant she was actually busier than if she had ‘just’ been an employee. Katie Brownlow was holding off from getting a ‘career’ job and was temping to accommodate her rowing. “We were all juggling huge commitments work-wise,” Tish Reid reflects, which put everyone under a lot of stress even before the pressures of racing at international level.

Winter racing and trials

GB-France international match (28 September 1991)

But first, some of the squad had a bit of fun at this ‘jolly’ in Paris which was organised and paid for by the French, and took place on the Seine near Notre Dame. Five GB men’s crews and the 1991 GB women’s eight (with Ali Gill instead of Sue Smith) competed. They were given white lycra to wear and it rained. You work it out. A lot of wine was involved, apparently – quite a lot of it BEFORE racing. It was televised and didn’t happen again (despite the transparent wet lycra), facts which may have been related. Only the men’s eight won. Zut alors!

Training started officially on 1 October, 10 months before the Olympic finals which were scheduled to take place on 1 and 2 August 1992.

BOA camp (11-15 October 1991)

This British Olympic Association camp was at the National Water Sports Centre (NWSC) in Nottingham but incorporated athletes from cycling, canoeing and taekwando as well as rowing (although unfortunately the martial arts experts heard two days into the camp that their sport was no longer an Olympic discipline). As well as some on-water training in which the forward-facing canoists and backwards-facing rowers mixed somewhat perilously, the programme comprised workshops, presentations and discussion sessions run by a range of professionals including doctors, psychologists, biomechanicians, conditioning advisers, exercise physiologists, physiotherapists, podiatrists, nutritionists and even a lifestyle advisor and a homeopathist.

Towards the end of the week there was a publicity session involving many of the athletes rafting down the white water canoe course next to the rowing lake at the NWSC for the benefit of press photographers. Unfortunately, Fiona Freckleton and several others seem to have picked up a bug from ingesting water during this.

Head of the River Fours (2 November 1991)

Ali Gill, Annabel Eyres (the 1991 double), lightweight international Vikki Filsell and the American, Thames Tradesmen-based sculler and Olympic medallist Anne Marden won the quads. Despite the bugs, Fiona Freckleton, Miriam Batten, Philippa Cross (three of the Vienna six) and Caroline Christie won the coxless fours.

Tiffin Small Boats Head (23 November 1991)

As was by now the established pattern, trials began with all squad hopefuls being encouraged to race at Tiffin SBH in singles and pairs (if trialling for the sweep group).

Note: Those who had already competed for GB at a World Championships or Olympics are in italics, and those who went on to do so in 1992 are in bold.

Singles

27 raced including both openweights and lightweights. As it was Olympic year, a number of athletes who had previously raced lightweight had switched to openweight because there were no lightweight events at the Games at this point, including Gill Hodges and Jo Toch who had both raced at the Olympics in 1980 and 1984, Rachel Hirst and Sue Key. At some point around this time Bob Michaels asked Katie Brownlow, who had stroked the lightweight four to two silver medals over the previous four years, to join the openweight squad, which she did.

- Anne Marden (not eligible for the GB team)

- Tish Reid

- Ali Gill

- Annabel Eyres

- Sue Appelboom (trialling for the lightweight squad)

- Sue Key

- Kate Miller

- Sue Smith

- Helen Mangan (lightweight)

- Kate Grose

Pairs (from different divisions)

- Philippa Cross/Kareen Marwick

- Philippa Cross/Caroline Christie

- Fiona Freckleton/Miriam Batten

- Sue Smith/Jo Gough

- Kate Grose/Suzanne Kirk

First 2,500m ergo test (late October 1991)

- Ali Gill

- Kate Grose

- Annabel Eyres

- Philippa Cross

- Fiona Freckleton

Based on her time to 2,000m, Miriam Batten would have been fifth but did not finish the piece.

British Indoor Rowing Championships (8 December 1991)

Tish Reid won the 2,500m women’s openweight event ahead of Anne Marden, finishing five seconds faster than Ali Gill. Annabel Eyres was the third British woman, nine seconds behind Ali but eight seconds in front of Miriam Batten.

Annamarie Dryden was the fastest lightweight woman, beating second-placed Ruth Rudkin comfortably. Astrid Huelin took the Under-23 event in a time that was two seconds slower than Annamarie’s.

From left, Katie Brownlow, Caroline Christie, Miriam Batten and Dot Blackie training at Henley in January 1992. (Photo: Miriam Luke’s personal collection.)

Second openweight erg test (January 1992)

- Jo Turvey

- Annabel Eyres

- Astrid Huelin

- Miriam Batten

- Flo Johnston

Fiona Freckleton, Ali Gill, Katie Brownlow, Kate Grose and Gill Hodges missed this test through illness or injury. Aggie Barnett and Tish Reid also did not do it for reasons not recorded.

Second open assessment (1-2 February 1992)

This took place at Henley and involved a lot of 3,000m pieces downstream.

Openweights

Session 1: Pairs

- Rachel Hirst/Jo Turvey

- Philippa Cross/Kareen Marwick

- Sue Smith/Suzanne Kirk

Session 1: Singles

- Anne Marden

- Annabel Eyres

- Kate Miller

Session 2: Fours

- Miriam Batten/Dot Blackie/Sue Smith/Kate Grose

- Gill Hodges/Suzanne Kirk/Sarah Merryman/Jo Toch

- Philippa Cross/Flo Johnston/Astrid Huelin/Kareen Marwick

Session 3: Fours

- Philippa Cross/Caroline Christie/Astrid Huelin (run 1) and then Sue Smith (run 2)/Kareen Marwick (results were from a double run)

- Miriam Batten/Suzanne Kirk/Sue Smith (run 1) and then Astrid Huelin (run 2)/Kate Grose

- Gill Hodges/Dot Blackie/Sarah Merryman and then Aggie Barnett/Jo Toch

Session 4: Fours

- Philippa Cross/Jo Turvey/Rachel Hirst/Kareen Marwick

- Miriam Batten/Caroline Christie/Sue Smith/Kate Grose

- Gill Hodges/Dot Blackie/Sarah Merryman and then Aggie Barnett/Jo Toch

Fiona Freckleton was not present.

Lightweights

Session 1: Pairs

- Tonia Williams/Annamarie Dryden

- Alison Staite/Alison Brownless

- Martha Sweeney/Vikki Filsell

Session 1: Singles

- Sue Appelboom

- Nicky Dale

- Trisha Corless

- Helen Mangan

Session 2: Pairs

- Tonia Williams/Annamarie Dryden

- Martha Sweeney/Vikki Filsell

- Sue Walker/Christine Brown

The Alisons did not take part in this one.

Session 2: Singles

- Trisha Corless

- Nicky Dale

- Sue Appelboom

- Helen Mangan

Sessions 3 and 4: Fours and doubles

Alison Staite/Annamarie Dryden/Tonia Williams/Alison Brownless were fastest both times. The other fours that took part were all club crews. Helen Mangan/Trisha Corless were the fastest double; Nicky and Sue apparently didn’t do these sessions.

Third openweight ergo test (mid-February 1992)

- Jo Turvey

- Fiona Freckleton

- Astrid Huelin

- Kate Grose

- Gillian Lindsay

CRASH-B World Indoor Rowing Championships: Boston, USA (16 February 1992)

Annamarie Dryden won the lightweight title, breaking the existing record by 14 seconds, and Tish Reid also competed, apparently making the final. The organisers paid their travel and accommodation expenses as British champions.

The squad didn’t enter a crew at the Women’s Head on 14 March, but the athletes were released to row with their clubs. The Tideway Scullers crew that won by eight seconds from Thames contained seven current GB squad members: Kate Grose, Annabel Eyres, Kareen Marwick, Suzanne Kirk, Kate Miller, Jo Toch and Gill Hodges.

Third open assessment (21-22 March 1992)

Again, this involved 3,000m downstream pieces at Henley, but was mainly for lightweights with only a few openweight pairs and singles taking part.

Session 1: Openweight pairs

- Rachel Hirst/Jo Turvey

- Kate Grose/Dot Blackie

- Sue Smith/Suzanne Kirk

Session 1: Openweight singles

- Tish Reid

- Annabel Eyres

- Kate Miller

Session 1: Lightweight pairs

- Tegwen Rooks/Claire Davies

- Tracy Bennett/Vikki Filsell

- Tonia Williams/Annamarie Dryden

Session 1: Lightweight singles

- Helen Mangan

- Sue Appelboom

- Trisha Corless

Session 2: Lightweight doubles

This was won by Helen Mangan/Nicky Dale with the other three crews were quite a long way behind them.

Session 2: Lightweight pairs run 1

- Annamarie Dryden/Vikki Filsell

- Tonia Williams/Tracy Bennett tied with Tegwen Rooks/Jane Hall

Session 2: Lightweight pairs run 2

- Annamarie Dryden/Vikki Filsell

- Claire Davies/Tegwen Rooks

Trisha Corless was the fastest of the small number of lightweight single scullers who raced in Session 2.

Session 3: Lightweight pairs

- Annamarie Dryden/Vikki Filsell

- Tegwen Rooks/Tonia Williams

- Jane Hall/Tracy Bennett

Interlude: Fiona Freckleton’s health

Readers may have noticed that Fiona missed the second ergo test and the second open assessment because she was ill. These incidents eventually turned out to be more than mere colds, as she explains.

“The 1991/1992 year started well. We were absolutely determined after our medal in Vienna. We had lots of confidence and we just threw ourselves into training. I remember we were doing things like two hours on the ergo with 2’00″/500m splits, so it was proper, hard training. It wasn’t very low intensity. We’d both been ill before Christmas, and we basically needed a rest. [Although Fiona, who was a teacher at Westminster School, had generously been given a much reduced timetable for the first two terms of the academic year, she stresses that she didn’t miss a lesson even when she was ill – Ed.]

“Every so often we’d go out and we’d perform. Whenever there was something like an ergo test we’d be alright, but I was very up and down. I had a reasonably good January, but we were all given flu jabs by the squad doctor around then and though I wouldn’t blame him for it, from that moment onwards I was in trouble. I remember turning up to training and Pete Proudley just looked at me and said, ‘Go home because you look awful.’ I’d had a really bad sort throat and I didn’t go to the doctor, but I got the school nurse to give me some antibiotics, which was probably the worst thing because I actually had glandular fever and they don’t work on that and they also suppress your immune system, I think.

“I was sent off to the British Olympic Medical Centre for a blood test but as I understand it the doctor never sent it off [and had it been sent off she would surely have been given the results –Ed.]. So I basically trained from early February through to the middle of April with glandular fever without knowing that’s what I’d got. On top of that, the doctor had this big thing that the reason I sometimes did really badly against the others because was we’d won a medal and couldn’t cope with the pressure.

“Whenever I got to the point where I’d just basically fail, the coaches would say, ‘Well have some time off,’ and so I’d have a day off but then I’d think, ‘Oh, I feel a bit better,’ so I’d go for a bike ride or a run or do heavy weights on my own without them knowing because I didn’t want to fall behind, and anyway I was being told there wasn’t actually anything wrong with me, it was all in the mind.”

FISA camp (22 March-12 April 1992)

FISA, the governing body of world rowing, had organised an altitude training camp in Mexico City (at 2,250m above sea level) run by the coaching guru Thor Nielsen at which each national federation was offered two places. Fiona Freckleton and Miriam Batten were chosen to go. “I think Bob thought that it would be good for us because we could go away and train away from the team and be with someone who is really eminent, and there would be good medical support,” Fiona Freckleton says, adding, “We had a really useful three weeks there. It was great.” Miriam remembers that she was coming back from having had a bad back for a while at that point.

World Cup I: San Diego (4-5 April 1992)

Single sculler Tish Reid was the fastest qualifier for the small final.

Scullers’ Head (11 April 1992)

Anne Marden won the women’s pennant with Tish Reid the fastest British woman in second place, and Helen Mangan third, 0.3 seconds ahead of Trisha Corless. Sue Appelboom was next, a further 5.6 seconds down and Kate Miller after that, but it was not an event that was part of the openweight squad’s schedule that year, not least because their crew formation trials began the next day.

Selection camp and trials (12-16 April 1992)

The trials involved 2k pieces in Nottingham in singles, pairs, doubles and fours, but bad weather meant that they were done in a head race format because of unfair lanes. 20 athletes and one cox were selected to attend although two of the athletes are unnamed in the information document issued on 29 March. As well as the 17 athletes who eventually raced, the group included Sue Key and the perennial sub Kate Miller. The two un-named women are most likely to have been Caroline Christie and Gill Hodges. Suzanne Kirk remembers that she and Sue Smith tied for first place with the pair of Dot Blackie and Kate Grose.

Fiona Freckleton and Miriam Batten only joined the camp from 15 April after they returned from Mexico. Some of the other women felt that they were at an advantage for the final trials because they’d been at altitude, while they counter that the long journey back was detrimental. Both seem likely to have been true to a greater or lesser extent and so largely cancel each other out, “But that obviously really upset people,” Fiona says, “And I can see why. I really understand that.”

Rowing magazine reported that the women’s team trials were inconclusive [in terms of the sweep boats] and that decisions were deferred until further seat racing was conducted at the team camp which followed immediately.

Ali Gill rowed at the trials in a double with Tish Reid because Annabel Eyres was out with a back injury, which has more significance than it sounds as the squad management had been pressurising Tish to get into a crew boat for a long time. At Lucerne regatta in 1991 the Director of International Rowing Mark Lees had unexpectedly told Ali Gill and Annabel Eyres, immediately after they had come an impressive fifth there, that Ali was to scull with Tish instead, despite not having consulted either Ali or Tish first, and despite there only being just over a month left until the World Championships, during which time there were no more regattas at which to try a new combination. Ali was against the idea for a number of reasons, and Tish was against it primarily because she was committed to single sculling following disappointing experiences in crew boats in the past, and as she had proved herself to be the fastest British single sculler, was providing her own equipment, using her club’s training facilities and working with her own coach, felt it unreasonable for the management to tell her what she should do. “Having also gone part-time at work, I didn’t want to be making all those financial sacrifices to be forced into a crew again,” she says.

As she was clearly a fast sculler, the whole matter didn’t go away, and had flared up again at a squad training weekend in January 1992 which Tish felt forced to leave when she was told to scull in a double.

Thinking back on this time now, Tish says she can’t remember how the rift with Bob Michaels was repaired (which it was by then as she attended the squad camp in Banyoles following the Nottingham camp), but agreeing to double with Ali at the trials as a one-off may have been part of it, perhaps to record some times in that boat type as a baseline. “There was never any question I would be in that boat, though,” she says.

Olympic team camp (19-28 April 1992)

18 rowers/scullers and cox Ali Patterson attended this camp in Banyoles including former lightweight Katie Brownlow who had had a back operation in January and been out since then. Tish Reid didn’t attend because her coach had been excluded.

After some seat racing, Bob announced the sweep crews. The double, pair, and four were kept as they had been in 1991. The eight was a standalone crew with no one doubling up in it from the four or pair.

Eight

B: Kim Thomas

2: Aggie Barnett

3: Dot Blackie

4: Gillian Lindsay

5: Kate Grose

6: Sue Smith

7: Suzanne Kirk

S: Katie Brownlow

Cox: Ali Paterson

Coxless four

B: Kareen Marwick

2: Rachel Hirst

3: Jo Turvey

S: Philippa Cross

Coxless pair

B: Fiona Freckleton

S: Miriam Batten

All but Gillian Lindsay and Dot Blackie had previous senior international experience; Gillian, who would still only be 18 at the time of the Games in 1992, had been in the GB junior team for the previous two years. Kate, Sue and Kim had all raced at the previous Olympic Games in 1988, as had Ali Gill.

Sue Key was dropped from the team after trials at the camp against Caroline Christie, who became the named ‘spare’.

The wash up report compiled by the team after the Olympics noted that not enough training was done at the Banyoles because of the need to wind down for Cologne regatta, and felt that either they should have targeted another regatta [although there wasn’t one – Ed.] or the camp should have been held earlier.

Quite a few unhappy faces at the end of the camp.

Back (from left): Jo Turvey, Ali Gill, Dot Blackie, Sue Smith, Katie Brownlow, Caroline Christie, Suzanne Kirk, Kim Thomas, Miriam Batten.

Middle: Philippa Cross, Kareen Marwick, Sue Key, Kate Grose, Ann Redgrave (team doctor), Gill Hodges, Rachel Stanhope, Aggie Barnett, Fiona Freckleton, Bob Michaels.

Front: Pete Proudley, Ali Paterson, Natalie Redgrave (baby), Wendy Green (team physio), Ron Needs.

(Photo: Dorothy Roberts’ personal collection.)

For the openweights there would be just three regattas at which to prove themselves. The pair and the double only raced at two of these, which isn’t a lot of data points in an outdoor sport where times are heavily affected by wind. Kate Grose’s memory is that from the outset, “The eight was very obviously the ‘bucket’ boat and Bob made it as clear as he possibly could that we were not going to be selected,” although Sue Smith doesn’t remember Bob even paying them enough attention to say that.

Interlude: Fiona Freckleton’s health – update

“After we’d got back from the Banyoles camp, I finally got to see a specialist who had done a lot of research into over-training and things like that, and he’d developed what he called a complete illness screen, which involved him load of blood samples,” Fiona explains. “I remember him ringing up and him saying, ‘Well, you’re almost better now but you have had glandular fever, there’s no doubt about that because you’ve got the antibodies and you’ve still got signs of the virus.’

“The implication was that although I’d been ill I was now basically almost better, so in a way that was good news because it explained it all after months of not knowing where we were but I was also concerned because I didn’t really know what that meant. I didn’t know when I was going to get better.”

The Almanack report on the year, written some time after the Olympics, says, “Looking back now, it’s clear that a decision should have been made much earlier to drop Fiona from the pair.” Looking back at it now, more than 25 years later, Fiona reflects, “I think Bob probably was wrong but I know what he was hanging on for, I know that he really believed that Miriam and I as a pair had it in us. The first two pieces we did in Banyoles once we’d acclimatised, we flew, we beat all the other pairs, and that gave us and Bob the idea that we were alright.”

She adds, however, that while she, Miriam and Bob knew that she was meant to be getting better, she appreciates that the rest of the squad probably didn’t know this and so understands that they felt she should be dropped. “It was really difficult for the others, I know it was. I think they just felt that we were protected, which we were, but it was because Bob knew that we still had the potential.”

Lightweight training camp in Amsterdam (Easter 1992)

The lightweight four was named as Alison Brownless, Claire Davies and Annamarie Dryden who had been in the crew the previous year, and all lived in London, with Tonia Williams, who had been in the lightweight double in 1991 and was based in Nottingham.

Bill Mason wrote later, “From the physiology side it had good potential but still needed considerable improvement in technique and compatibility.” This may have been him putting it politely: all four members of the the crew admit that it was very much three plus one, the one being Tonia. This was true in terms of the ‘three’ having raced together the year before, of geography, and of style, and with Tonia in the stroke seat, the other three all needed to adapt.

One way that this was supported was through rigging: Tonia had a long body swing although like Wilma at bow tended to over-reach, whilst Annamarie at three had a shorter upper body and, “Had difficulty pivoting fully from the hips”, according to Bill. As a result, to bring everyone more together, he changed Annamarie’s span and the inboard on her blade, although her blade length remained the same overall (this was before the days of adjustable-length blades), and had new stretchers made at a sharper rake to discourage over-reaching at the catch. ” There’s usually a lot of sneaky measuring of equipment that goes on at international regattas,” Tonia says, “And our rig really flummoxed everybody!”

Cologne (2-3 May 1992)

The racing season got off to a bad start when the GB trailer with the women’s boats on was involved in an accident on the way to Cologne. Dot Blackie remembers that they’d just got a brand new Sims eight (on the top in the photo below) which they therefore never even raced. The one they finished up using was warped, Suzanne Kirk recalls, which led to many arguments about balance and as to whether this was why it wasn’t running straight. “Ali Paterson was saying that bowside weren’t pulling,” she explains, “But I knew that wasn’t the case. The boat was down in the stern on bowside but the bows were saying that it was down on strokeside, and it was horrible because it was twisted. Bob wouldn’t check it, even though in our Sims it had been fine, so it was a bit of a fiasco.”

Disaster. (Photo: Dorothy Robert’s personal collection.)

Tish Reid won the small final of the single scull in what was another round of the World Cup series in a time that was less than two second slower than that of the bronze medallist, albeit in a race rowed at a different time. Rowing commented, “The arguments over whether she has enough class to be selected in the single scull must now be won in her favour. Provided she can maintain or even improve on this result at Essen and more importantly Lucerne.”

The coxless four came second on both days behind Germany, a little over three seconds down each time.

The GB openweight 4- (nearer the camera) racing with conventional macon blades (more on this below). From left: Philippa Cross, Jo Turvey, Rachel Hirst, Kareen Marwick. (Photo © Maggie Phillips.)

The eight was third on the Saturday, nearly 11 seconds off gold, but only two lengths [six seconds] down on the second day. A major reason for the turnaround was that Suzanne Kirk, who was still in the seven seat, was suffering from such terrible abdominal cramps on the Saturday that she couldn’t stand up straight, but coach Jon Tompkins had told her that she had to race because there wasn’t a sub. She took what she describes as “too much ibuprufen” in an unsuccessful attempt to reduce the pain, leaving her altogether in an unfit state to row. Not surprisingly, “I rowed really badly,” she says. By the Sunday she was feeling fine, “But the eight had done very, very badly and Bob then swapped everyone in the eight around and I ended up at two, and he told me my rowing had been short and stabby.”

Ali Gill and Annabel were entered in their double and in singles as well but don’t seem to have raced, at least partly due to the trailer accident. The pair didn’t go either.

Big blades

Cologne Regatta 1992 hit the headlines throughout the rowing world because it was the first international event that saw a sizeable number of crews (although not any of the GB boats – men’s or women’s) racing with the new ‘hatchet’, ‘meat cleaver’ or simply just ‘big’ blades rather than the macon shape which had become the norm in the late 1960s (when, ironically, they were often referred to as ‘big blades’ compared with the ‘needle’ shape which had been used since the nineteenth century). Although various asymmetric blades had appeared from time to time in the 1970s and 1980s, none had caught on. This time the new design, first raced with in October 1991 and backed by the marketing savvy of the US producer Concept 2, was taken much more seriously.

Bill Mason noted, in relation to lightweight sculler Sue Key (but the point applies generally), that they were particularly advantageous off the start, although making the most of them in that part of the race required additional strength.

One of the issues with the new ‘big blades’ was that they were about more than just spoon shape: the innovation opened up the whole question of how best to rig a boat. It was generally understood that they needed to be shorted than macons, but how much shorter? And should the span be made narrower too? No one really knew, and there was precious little time before the Olympics and World Championships to start testing, which is practically impossible to do scientifically in rowing anyway. Quite how non-fine the tuning was is revealed in notes Bill Mason made about the lightweight four’s blade which he shortened by a whopping 1.5cm on their pre-Championships training camp.

Interestingly, the Norwegian men’s quad which won the silver medal at the Olympics used wooden macons and a wooden boat.

Ghent (9-10 May 1992)

Lightweight Trisha Corless won openweight singles comfortably, while the eventual under-23 double of Caroline Dring and Adrienne Seaman took bronze in the open event at Ghent where almost all entries were from top club crews rather then international squads.

Essen (16-17 May 1992)

Essen was one of the major early season regattas and a lot of countries were there including loads of Germans, of course, but also the Canadians, French, Chinese, Dutch, Czechs and Romanians. There were no American, Australian or Russian crews, though.

The GB women’ team’s accommodation was above a petrol station, which was apparently not salubrious. The men’s team were elsewhere.

Miriam and Fiona in the pair planned only to race on the Saturday and qualified for the final by coming second in their heat where they recorded the third-fastest time out of the 13 crews in the event, which was promising. In the final, though, they finished sixth, over nine seconds off the bronze medal, beaten by two Canadian, two German crews and a French one. However, Fiona Freckleton remembers, they should have finished fourth or fifth but unfortunately, “Miriam managed to think that the 100m to go marker was the finish line and we stopped rowing. But we were in the race and given where we’d been [performance-wise], we thought that this was another indication that we could do it, although it was tricky for poor old Bob.”

The challenge for Bob was that, having not raced at Cologne, and only done one of the days at Essen where their actual placing was almost certainly adversely affected by the confusion about where the finish line was, he only had a single, imperfect piece of information to use as the basis for deciding whether to persevere with the pair or not. In favour of keeping them together, along with the moderately positive indicator that their Essen result represented, was the fact that there were still over two months until the Olympics started. On the other hand, they actually only had one more regatta to race at before then, so if things turned out badly there, there would be no further opportunities for a new combination to race against real opposition.

Annabel Eyres and Ali Gill, now fully fit after their consecutive back injuries, hit the ground running in their double. They decided they would only race on the Sunday, and won. But, Annabel remembers, they had been given some of the new big blades to use, “So that put a bit of a question mark on our performance. We were quite shocked that we’d won after so much time off, and the crew that we beat were saying, ‘It’s those blades, it’s got to be those blades!'”

The eight and four both raced on both days. On the first day, after winning their heat, the eight came fourth in the final, 10.55 seconds behind the winners, while the four was fifth, 7.91 sec off the gold medallists but “in the pack” according to Regatta. Both crews got the same results on the second day but the eight, which on that occasion had Miriam Batten and Ali Gill on board instead of Aggie Barnett and Gillian Lindsay, halved the distance they were off the Romanian winners to five seconds.

Kate Grose says, “After the Saturday final we all realised that we could have done better but we’d had our confidence fairly badly knocked by being told how bad we were and Bob suddenly noticed that the eight was actually not quite as bad as he’d expected. He came to talk to us on the Saturday evening and said, ‘Tell me what you’re going to do tomorrow,’ and I said, because I really, truly believed it, ‘I think we can go nearly two lengths faster if we actually believe we can build on today because what we did today was good, it was so much better than we thought we could do, and people won’t see us coming.’ And Bob said, ‘Hmm, two lengths is an awful lot in an eight,’ but I said I thought that was what we can do. And the next day we went out and went faster.”

While not disagreeing with Kate, Suzanne Kirk adds, “We all knew that Miriam and Ali were good but they didn’t on their own make the boat go five seconds faster. But what they did do was bring a feeling to the boat that actually we’re good, and I can’t speak for anybody else but I feel it’s nice rowing with people that are really good and really successful, and it makes you as an individual raise your game because you want to be that good, and so they made us all row better and that was also a factor in us going that much quicker.”

The four also did a little better, coming second in their heat but fifth in the final where all three crews which had qualified from the other heat – in slower times than the British – took the medals. The GB crew was six seconds off first place.

The journalist Chris Dodd wrote that, “The eight had an impressive row,” and “The four were also well up with the pack.”

Two GB lightweight fours finished first and third on the Saturday, 14 seconds apart. The top boat scratched on the second day as Annamarie Dryden had gone down with a cold, and the second crew came sixth.

Sue Appelboom won the lightweight singles on the Saturday with Trisha Corless third, six seconds behind her, and Helen Mangan fourth, just 0.33 seconds further back. On the Sunday Sue was second, just over four seconds ahead of third-placed Helen Mangan.

Living apart but rowing together: the geographical challenge for the lightweight four and double

What do you do when the best rowers live over a hundred miles apart? This is the conundrum which has faced national squad crews (and, indeed, other national team sports) forever, and although it’s largely ‘solved’ today by having a national training base at Caversham and funded athletes who therefore have to live there, it certainly wasn’t practical when international rowers had jobs.

Tonia Williams, the commuter in the lightweight four took inspiration from Rachel Hirst, who had rowed in the London-based crew in 1989 and 1990 when she too lived in Nottingham. Although the London contingent did travel north sometimes, it was mostly Tonia who spent time driving up and down the M1. “Ann Redgrave, who was team doctor, told me that every long journey I did was as tough on you as a training session because you’re concentrating and you’re sitting in the car, so your load mentally and physically is increased because of the commuting. But though I was thrilled to have the opportunity, it did mean that life was in limbo because you were separated from your friends and your contacts and everything you did socially in Nottingham, and you didn’t really fit in with the London thing either,” she reflects.

After Essen, Trisha Corless, who lives in Staines, Surrey was teamed up with Helen Mangan, who was a member of Runcorn RC in Cheshire, in the lightweight double. They were only able to train together at weekends, and usually did so in Runcorn, as Helen’s coach Rosie had international experience, and as Helen had a young son.

The cut to 20 for the Olympic squad (21 May 1992)

Following the April selection camp and Cologne and Essen regattas, a list of 20 names was issued (19 athletes and cox Ali Patterson) from whom the Olympic crews would be selected. It stated that “The list is now ‘closed’ and only in the event of an injury, or an athlete failing to comply with either the Amateur Rowing Association or BOA selection criteria, will any other athlete be considered for the Olympic team.

The 19 did not include Astrid Huelin who was eventually named as an official sub, but did include Gill Hodges who was not selected in the end.

Kate Grose remembers, “We had thought at that point that changes might be made to the eight, and although in a way we didn’t want changes because we were having fun, we actually sort of hoped there might be. But we were told that there were no further changes going to be made and so we went off to Lucerne.”

Paris regatta (30-31 May 1992)

Only the lightweights and a few openweights who were no longer in the main squad raced at Paris where the weather was very hot and the boats arrived late.

On the Saturday, Sue Key finished seven seconds ahead of Sue Appelboom in the lightweight single sculls with Nicky Dale third, 16 seconds further back, and Phoebe White another six seconds back. The next day Sue Key beat Sue Appelboom again but only by 0.4 seconds this time. Phoebe White came third and Nicky Dale fourth, one second apart but a long way back again.

7 seconds vs 0.4 seconds?

The reason for the two very different margins between Sue and Sue was that Sue Appelboom caught a monster crab off the start on the first day. Mike Rosewell summed this up in an unidentified newspaper clipping, saying, “The Paris racing did little to clarify women’s lightweight selection. Sue Appelboom, the 1991 GB lightweight sculler, was beaten on both days by Sue Key who has shed almost two pounds since being dropped from the GB [openweight] squad almost three weeks ago.” Although Sue Appelboom entirely accepts that catching a crab was her fault, she did point out to the squad management that the result wasn’t indicative of their comparable racing speed.

Kate Miller was fourth in openweight singles.

As there was no event for lightweight fours the GB lightweights raced in openweight coxless four where they came were fourth on the Saturday and third on the Sunday, despite their being a strong headwind which favoured heavier crews. In the openweight doubles, lightweights Helen Mangan and Trisha Corless (who’d had their first outing as a crew a week earlier) were second on the Saturday, three seconds behind the Romanian winners, with Caroline Dring and Adrienne Seaman fifth, quite a long way further back. Dring and Seaman were also fifth in openweight doubles on Sunday when Mangan and Corless came second in lightweight doubles.

Lucerne (12-14 June 1992)

And so to the final international regatta before the Olympic Games, which was held considerably earlier than usual to fit in with them.

Simple stuff and good news first [readers can see some excellent photos by Peter Spurrier by clicking each crew name]: Helen Mangan and Trisha Corless got the silver medal in the lightweight double, finishing 3.95 seconds down on the winners despite being having been in sixth place after the first 500m. Trisha says, “I remember racing down the course and nearly at the end Helen shouting, ‘We’re second!’ It was quite a big thing.”

The lightweight coxless four, which had won its heat, and lightweight single sculler Sue Key both took bronze. The four had actually been in second place for most of the race but was rowed down in the last 300m. In Sue’s case the two scullers who beat her were both Danish, which boded well for the World Championships where only one of them could race, while the outlook for the four was similar as the two crews which beat them were both American, although some of their expected challengers were not there. Chief Coach Bill Mason described their achievements as “magnificent,” and the journalist Mike Rosewell quoted him as saying that, with a new boat about to be delivered for the four, “They have a lot to come.”

The journalist Chris Dodd wrote in the Guardian, “Sue Key probably ended the selection challenge from Sue Appelboom by finishing third. Appelboom, laid low with a virus, has lost to Key three times recently.” It’s not clear what the third occasion was (two of the occasions having been the two separate finals at Paris regatta), unless he means a heat at Paris, and Sue Appelboom doesn’t particularly remember a virus keeping her away from Lucerne. Rather, she says, she had understood that she would not be selected ahead of Sue Key so had elected not to race at Lucerne as, at that time, lightweights had to pay the entire – considerable – cost themselves.

The openweight double also did really, really well, winning the bronze medal. Dan Topolski wrote in the Observer, “Ali Gill and Annabel Eyres have moved up a class since last year and a first British Olympic meal for women is now on the cards,” while Geoffrey Page added that they “excelled” in finishing behind “two top class former comprised of former East German gold medallists,” and Mike Rosewell said that they, “Are beginning to look like medal prospects for the women in Barcelona.”

“That was about the most brilliant race I ever had,” Annabel remembers. “On the morning of the final we walked together from the hotel in perfect time all the way and it was like we were just completely a unit and it felt like that when we started the race. It felt easy. It was the most amazing feeling and you could see these East Germans thinking what the heck are these Brits doing there?!”

Tish Reid came ninth in the single sculls which, as Mike Rosewell put it is a marginal selection decision, but three Germans were ahead of her and only one will attend the Olympics.”

The eight, which Hugh Matheson described as coming “a sparky third” in its heat, finished fourth in the final, just one length behind third-placed USA, nine seconds off gold, a performance which Rosewell called “creditable”. After they’d crossed the finish line, Suzanne Kirk says, “And once I’d got past that ‘Crikey, am I going to die?’ bit, I turned round and the Canadian women, who’d got the silver, were looking at us with respect. They were impressed. And I remember thinking, ‘This is it, we’ve arrived, going into the Olympics this eight is in touch. It was brilliant! It was just the most magnificent feeling, we were rowing really well.” She adds, “We’d become a crew. Jon Tompkins was a brilliant coach and he had this fantastic spiel that he’d done with us where he went through everybody’s strengths to say, ‘This is why you’re in this crew,’ letting everybody know how good everybody else was at something, and it was fabulous, and we were a very, very tight knit, very effective crew.”

Jon briefing the eight in Lucerne. (Photo: Dorothy Roberts’ personal collection.)

Like the eight the coxless four was also nine seconds off gold but they were in seventh place and it was placings that mattered. Dan Topolski described them as having “failed to find their form” compared with their fifth place at the World Championships the previous year.

The GB four (third from the camera) off the start in Lucerne. (Photo: copyright owner unknown)

Worse still, the pair had to withdraw before the final. “We rowed our heat on the Friday and came last but for the first 1,000m we were up on the French and the Romanians,” Fiona says, looking back at her training diary. “And then I’ve just put, ‘The lights went out.’ We just had no power and we were eight seconds behind the next boat at the end. We obviously just ran out of steam, and I think exactly think happened in the rep. We actually led the rep, we were in front as we went through half way in perfect conditions. We were with the Germans, we were definitely in front of the Romanians, but I just couldn’t do the second 1,000m. I just wasn’t there. I was dizzy, I wasn’t on the same planet. I simply didn’t have it in me. We scrambled to the line and I spent the rest of the day asleep. I was beside myself because I knew it was the end. I knew that it was now too late.”

She adds, “I’d always done quite badly at Lucerne because it was at the end of the school year and teachers are always exhausted by then, but I perked up during the summer holidays before the World Championships. So there was part of me that said, ‘This is just Lucerne.’ But school had given me a sabbatical from Easter onwards so when I bombed out at Lucerne in 1992, it wasn’t because of school, it was because I was unwell, or actually that I had been unwell because by then I was getting better and though I didn’t feel fine, I didn’t feel as bad as I had done.”

The pair hadn’t actually complete a competition that year to their satisfaction: after missing Cologne, they had done just one of the days at Essen where they wound down by mistake for a few stroke 100m before the finish line, and then withdrawn before the final at Lucerne.

Kate Grose’s recollection of the targets the sweep group were told they had to achieve at Lucerne in order to be selected to go to the Olympics were that the pair had to make the semi-final because that event had quite a big entry; the four had to make the final because there was a smaller entry in that; and the eight had to win a medal because there were even fewer eights. Although this seems plausible and was the type of target often set, others don’t remember this; Suzannne Kirk recalls how delighted the eight all were with their performance in the final, and points out that they wouldn’t have been so happy had they known at that point that not medalling meant they wouldn’t be selected.

So, what next?

The problems were clear. The main one was that, at that point, Fiona Freckleton was not up to racing and no one knew how her recovery would progress in the five to six weeks between then and the Olympic Games. At the same time, whether because more countries had put out top coxless fours than they had the previous year, and/or whether the British crew hadn’t progressed as much as other nations in the past ten months, the GB four, which was meant to be one of the two priority sweep boats, looked like it might well not even make the Olympic final never mind be in contention for a medal. Alongside this, the eight, made up of the ‘second tier’ athletes, had increasingly shown itself to be competitive.

Yet while the analysis was simple, the solution wasn’t. Mike Rosewell wrote after Lucerne that, “There may be a case for reshuffling the women’s pack to strengthen the eight.” After some thought, Miriam now thinks that the pair should probably have been abandoned and she should have been put into the eight. However, Bob may have been keen to keep the pair to ‘get one over’ on Director of International owing Mark Lees, with whom he didn’t get on at all, and who had initially refused to select the pair of Miriam and Fiona the previous year. Fiona suggests that the Bob should have left all the crews alone. “I think we might still have made the final, although I don’t think we would have medalled,” she says.

Fiona remembers, “Bob had a chat with Miriam and me, but as he often did, he didn’t say exactly what he meant but worded it as a riddle. He admitted that it was his fault that he’d pushed me when I was ill, but then he said that he expected that on the third of August I’d still be a very happy person. That would be the day after the Olympic finals, and this shows how much he believed in the new eight because what he was saying is that he thought the eight would medal.” But, she adds, “It was the wrong thing to do [to change all three crews], and with hindsight he should have changed the crews much earlier.”

The crews were called to a meeting at the ARA and Bob announced completely rearranged crews. Jo Turvey, who had previously been in the four and was established as the top bowsider, was put in the pair with Miriam. The prioritisation of the eight and four was swapped so that the four was now the third boat. Four women who had been in the eight became the new four, and the three that were left from the old four were put into the eight along with Fiona. To outside observers and some of the eight, it was hard to see why Fiona was in the eight if she wasn’t well enough to race in the pair: his thinking was, however, that she would be well enough but, by putting her in the eight, she could be replaced at the last minute if she became ill again without affecting the crew much, whereas changing one person was much more disruptive in a smaller boat.

When the GB team was announced, Geoffrey Page wrote that the “reinforced eight… could be an exciting prospect”, while Hugh Matheson’s prediction for the new pair was that, “Bob Michaels has cause to hope that Batten’s racing nous and Turvey’s strength may produce another medal in an event which is not as daunting a in many past years” [a comment presumably based on the quality of the crews which had been racing so far that season; no one yet knew how many pairs there would be – in fact it was a new high of 13 – because the entries had not yet closed.]

Laying aside the lack of opportunity to race in the new lineup, the eight did have quite a lot going for it on paper. In reality, though, it had been set up to fail in terms of working together as a team.

Kate Grose remembers, “We were devastated when we were told that four of our eight would be taken out and that all three remaining people from the four would be in the crew instead. As far as we were concerned, they had been told all year by Bob that they were the golden girls; nothing they did was wrong and we were deeply resentful. They’d been told that we were rubbish and wouldn’t get selected, although by then we’d proved we actually weren’t rubbish. But it all meant that they didn’t want to row with us and we didn’t want to row with them,” a conclusion with which Sue Smith agrees.

“If you put basically a whole crew into another crew, it’s too much,” Kate continues. “We’d been a crew that was better than the sum of its parts, and I don’t think Bob or any of us recognised that. I felt Bob was desperate to protect his ‘kebabs d’or’ and to keep them happy, and that’s why he put the four into the eight, and he didn’t consider the effect this would have. A bit later when it was all starting to go horrendously wrong, our coach, Jon Tompkins sat us all down and asked us all to say why we thought the boat had started going worse than it had up to Lucerne when it should have been better.” Dot Blackie, who was new to the squad, remembers being surprised at the amount of unhelpful personal ‘history’ between various members of the crew. “Almost everybody was resentful about something that had happened,” Kate concludes. One of the others who wasn’t resentful was stroke of the eight, Katie Brownlow who, perhaps alone of the Olympic team, doesn’t actually think she should have been in it at all. “When I look back on it now I think it was ridiculous that I was in it. I’m not particularly tall and I’m not particularly muscular, and I’d had a back operation in January,” she says.

Even after the seismic rearrangement of the crews, the new four was faced with further uncertainty, Suzanne remembers, “Because Bob announced that it was going to be me, Aggie, Kim Thomas and Gillian Lindsay from the eight, but Caroline Christie as well. After he read that out at the meeting I asked, ‘Which of us are going to row in the boat for the first outing?’ He asked what I meant and I said, ‘Well, we can’t all five of us row in it,’ which got a laugh from the rest of the room, and he looked a bit flustered and said that I would be in it for the first outing but I was racing Caroline Christie for my place.” In the end, she stayed in the boat, though she doesn’t recall a formal trial. She adds, “There was a massive amount of fear in the squad because Bob had made it very clear that if we complained about the crews we weren’t going to the Olympics. We were told that if we went to the papers or lodged an appeal, which people were talking about, we’d be dropped and wouldn’t go to the Games.”

Final selection for the Olympic team

Eight

B: Kareen Marwick (Tideway Scullers’ School)

2: Philippa Cross (Thames RC)

3: Fiona Freckleton (Westminster School BC)

4: Rachel Hirst (Nottinghamshire County RA)

5: Dot Blackie (Thames RC)

6: Sue Smith (Tideway Scullers’ School)

7: Kate Grose (Norwich RC)

S: Katie Brownlow (Thames RC)

Cox: Ali Paterson (University of London WBC)

Coach: Jon Tompkins

Coxless four

B: Aggie Barnett (Kingston RC)

2: Susanne Kirk (Tideway Scullers’ School)

3: Gillian Lindsay (Clydesdale ARC)

S: Kim Thomas (Weybridge RC)

Coach: CD Riches

Double scull

B: Annabel Eyres (Tideway Scullers School)

S: Ali Gill (Upper Thames RC)

Coach: Ron Needs

Coxless pair

B: Jo Turvey (Putney Town RC)

S: Miriam Batten (Thames RC)

Coaches: Bob Michaels and Pete Proudley

Single scull

Tish Reid (Lea RC)

Coach: Eddie Wells

Reserves

Caroline Christie (Thames RC)

Astrid Huelin (Thames RC)

The team was announced at a press conference in Henley where the photographer Peter Spurrier took some excellent pictures of the crews training:

Coxless four | Coxless pair | Eight

Smiles at a team press launch at sponsor Minet Insurance’s offices on 18 June don’t reflect everyone’s true emotions. (Photo: Annabel Eyres’ personal collection.)

Although there were five crews and the team was permitted to have five coaches accredited, the final frustration for Tish Reid, after what Rowing magazine described as “a long battle with the Chief Coach”, was that her coach Eddie Wells was not selected. “Bless David Tanner’s cotton socks, he made Ed the second trailer driver and that got him accreditation but he was never a part of the Olympic team, didn’t get the kit. It was one of those things I just couldn’t believe,” she explains. Looking at it more dispassionately, it may have more been a case of the management not considering her important than deliberately trying to ‘have the last laugh’: as the pair, which had long been Bob’s top crew, had two coaches, another boat’s coach ‘had’ to be omitted.

Amsterdam regatta (28-28 June 1992)

The lightweight four competed here, primarily so they had an opportunity to race their new boat which had been delivered a week earlier. They won, beating the Canadians by two seconds, a similar margin to the one they’d had over them in Lucerne.

National Championships (17-19 July 1992)

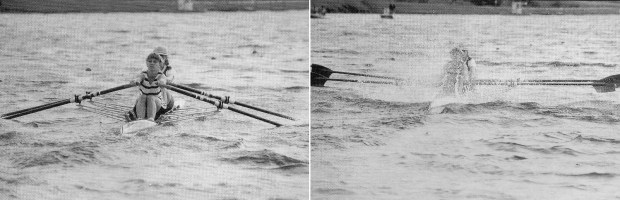

The only GB women’s squad boat at the National Championships was the lightweight double of Helen Mangan and Trisha Corless, who won both the lightweight and openweight events, finishing 21 seconds ahead on each occasion. The conditions were awful and Regatta magazine carried this striking pair of photos opportunely snapped by John Shore, captioned, “Now you see them, now you don’t,” taken during one race.

Photo © John Shore.

On the plus side, as Bill Mason wrote later, this allowed them to prove to themselves that they could cope with using the new big blades even in the worst of wind and waves.

The lightweight four had actually intended to race – again, so they could try out their new hatchet blades – but couldn’t as it was realised at the last minute that someone’s Amateur Rowing Association registration had lapsed. Instead they did a private trial against the GB junior squad in Nottingham, from which, Bill said, they concluded, “The crew had improved and the blades suited them.” Although Claire Davies took part in this race, she hadn’t trained in the boat between Amsterdam and Nat Champs because she was recovering from a rib injury she’d sustained after Lucerne. Jane Hall subbed in training.

Olympic training camps in St Moritz and Varese

With the decisions made, the team had about a week in Britain before heading to Switzerland and Italy for back-to-back training camps which were scheduled for 22 June-11 July and 14-23 July. For the first time the squad didn’t take part in Henley Women’s Regatta which was now run over two days on 20-21 June.

The aim of the St Moritz camp was to give the team an opportunity to train (and more importantly recover) at altitude. It has widely, and accurately been described as “a disaster,” for reasons that should have been within the management’s control as well as because of bad weather – which wasn’t anyone’s fault, but there also didn’t appear to be any contingency plans to cover this. Several of the team have questioned the very concept of sending them to altitude, and also criticised the location for only just high enough and that “the venue wasn’t properly researched”. This isn’t entirely accurate: the FISA coaching guru Thor Nielsen had run camps there for many years, and GB lightweight women had been going there successfully since 1985 (the lack of integration between the squads at the time explains why the openweight women were unaware of this). Whilst it was true that none of the 1992 squad had experience of training at altitude, which is often considered important to maximise the benefit from it, the decision to go there was also made against the background of justifiable complaints by the women’s team for some years that the men’s team was given opportunities that the women weren’t. The men were going to altitude at Silvretta in Austria.

Problems with the camp included the fact that the weather was unseasonably cold (and no one had enough kit for the conditions) and but more importantly it was so windy that it was frequently too rough to row on the lake except very early in the morning; Bob Michaels and CD Riches weren’t there for the first part of it because they had to be at Henley to look after their Westminster School crews (a consequence of only appointing a Chief Coach on a part time basis) and in those days before mobile phones this meant that Bob couldn’t even be contacted and therefore no one was really in charge; and there was no doctor present. Aggie Barnett suffered from an adverse reaction to being altitude (something that would have been known had it not been the first time the group had done altitude training) and went back to Lucerne to train on her own, which further limited the new four’s time to get together. “We were already fed up as the four,” Suzanne says. “We were really hurt about being dropped from the eight, because none of us could understand why. We were trying to adjust from being in a heavier boat where you’ve got a cox telling you stuff to a much lighter boat where you’re doing it all yourself, and then our coach wasn’t there and we didn’t even have the full crew. When Bob arrived I had a complete meltdown and asked if we could at least all go to Lucerne so we could train together. We wouldn’t get coached but we weren’t getting coached in St Moritz anyway. But he told me there was no money for that. It was such a fiasco, and there we were, moments away from the Olympics.”

On one day when it was too windy to row, Fiona Freckleton, who was a keen hill walker, let an ‘expedition’ up to a mountain hut. “But it poured with rain and those rowing waterproofs were pretty flimsy, so Sue Smith got a cold and was ill for the rest of the camp, and she wasn’t the only one. Rachel Hirst had quite a chronic back issue and she was normally alright but if she couldn’t warm up properly it bothered her, and it was really hard to warm up when we were that cold. Sarah Merryman [who had been dropped earlier on] flew out as a spare because official sub Astrid Huelin was at the Under-23 Championships. Other people were ill too.” On some of the days the walks in the mountains were in more pleasant, albeit windy, weather, but the feeling was one of being on holiday not preparing for the Olympics. The athletes’ washup report at the end of the season cited the camp as, “One of the single most obvious reasons for the team’s underperformance at the the Olympic Games.”

The plan for the final day was for every crew to do a 2,000m piece. The rain turned to sleet.

Tish felt that she was going ten seconds slower over 2,000m once she got to the Olympics as a result of missing training at such an important time by being in St Moritz.

Lost, in more ways than one? Kareen, Kim and Kate walk in the mountains when they can’t train. (Photo: Annabel Eyres’ personal collection.)

Kate Grose (left), Sue Smith and Kareen Marwick find alternative altitude training when rowing proves impossible. (Photo: Fiona Watson’s personal collection.)

The group then moved to Varese for heat acclimatisation, where some felt that things started to improve although it was too little too late, but others, according to the group’s washup report, “felt crew cohesion deteriorating”. Katie Brownlow remembers that Bob”washed his hands of the crew” after one outing. “He came up to me and said, ‘Kate, it is up to you, I cannot do anything with this crew, it is all in your hands now,’ and I remember that because I asked the team psychologist, ‘Can he do this? Is it my responsibility, is it all up to me whether or not this crew goes forwards or not?,’ and he said it wasn’t which I was very relieved about because that was not fair.”

Miriam, however, enjoyed rowing in the pair with Jo Turvey. “When I got in the pair with Jo it did go very, very well,” she recalls. “It was a good pair. So powerful.”

The four training in Varese but with Astrid Huelin subbing for Aggie at bow. (Photo: Suzanne Kirk’s personal collection.)

A press release must have been issued around this time as several newspapers printed Olympic preview stories within a couple of days of each other, all offering the same positive messages, though these seem to have been based more on hope than reality. Chris Dodd wrote in the Guardian, “There is quiet confidence abroad in both the men’s and women’s teams… The new pair have settled down, the women’s eight formed in mid-June is becoming a unit rather than rival factions.” He added that there are “medal prospects for at least three women’s crews” [presumably the double, pair and eight – Ed]. On 19 July Dan Topolski had reported in the Observer, “The women’s four and eight and Tish Reid in the single have still to find the speed that will win them places in the Olympic finals on 1 and 2 August,” but five days later he told the readers of the Evening Standard that, “The eight is beginning to click.”

The GB women’s rowing team at the end of the Varese camp. (Photo: Dorothy Roberts’ personal collection.)

At the Olympic Games

Opening ceremony

The rowing regatta always starts in the first week of competition at the Olympic Games, although not all boat types are scheduled on the first day of racing. As a result, many crews often don’t go to the opening ceremony, and even for those starting later it’s a tricky decision, particularly when the rowing venue – as it usually is – is away from the main stadium.

In the end the eight and Annabel Eyres went and but the others didn’t. “It was made very clear that everyone should make their own choice individually, not as a crew,” Ali Gill explains. “I was feeling ill and I’d also been to the opening ceremony in Seoul in 1988, but Annabel wanted to go. It didn’t cause friction between us and it is really hard because the Olympics are so amazing. You might never get to go again, and you just don’t know that.” Fiona Freckleton remembers the options being presented slightly differently. “We were all told we shouldn’t go to the opening ceremony, but we thought, ‘Actually, what are we here for? We talked about it as a crew and decided to go. But by the next day most of us were feeling queasy and I think we probably felt that we couldn’t really own up to that because everyone was going to say, ‘Oh you shouldn’t have gone should you?'” Kim Thomas remembers that the team were banned from eating Magnum ice creams which were free in the athletes’ village and also a novelty as the brand was new to the market then, after they’d had rather too many.

The eight and coach Jon Tompkins all dressed up to go to the Opening Ceremony. (Photo: Fiona Watson’s personal collection.)

1992 was the last time that live doves were released at an Olympic opening ceremony. Feathers and giant flaming cauldrons aren’t a good mix.

Racing results

Double scull (5th out of 13)

The entry of thirteen crews meant that the doubles would all have a first round heat, followed by a possible repechage, and then a semi-final and final.

“We had a disastrous first round,” Annabel Eyres remembers. They were fourth out of four with three to qualify directly for the semi-final, finishing seven seconds down on the third crew. Ali, however, was still ill and had lost a lot of weight, but had recovered considerably by the repechage two days later. With three crews having qualified for the semis from each of the three heats, the rep comprised four boats from which only one would be eliminated. The GB double won by a comfortable two seconds, watched by the Princess Royal.

The stakes in the six-boat semis the next day, of course, were much, much higher. Three would get through to the main final from each race, and the others would be relegated to the B final.

A photo of them going off the start in the semi-final (nearest the camera) can be seen here. Check out the bend on those blades!

After 500m they were fifth. And at half way, and at 1,500m. Then, as Annabel explains, “We charged. We had this brilliant Mike Spracklen-inspired finish which I think we had done the year before as well which is basically 80 strokes, 20-20-20-20, and you just build and build and build and that’s what we did.” After a photo finish, they were overjoyed when it was announced that they had got through, by 0.13 seconds. “We’d been way back, absolutely without a hope, and Ron Needs had apparently been watching on the monitor crying,” she adds.

This is what 0.13 seconds looks like. GB is at the bottom of the picture. (Photo: Annabel Eyres’ personal collection.)

The Chinese winners of their semi set a new Olympic best time in that race.

Two days later, they came fifth in the final, three seconds clear of the sixth placed Unified Team, although well behind the first four boats. The Germans won, lowering the Olympic best time by another nine seconds. Ali says, “I think we thought we had a really good race in the final. I came off the water thinking we’d rowed as hard as we could, but upset not to get a medal.”

Two days later, they came fifth in the final, three seconds clear of the sixth placed Unified Team, although well behind the first four boats. The Germans won, lowering the Olympic best time by another nine seconds. Ali says, “I think we thought we had a really good race in the final. I came off the water thinking we’d rowed as hard as we could, but upset not to get a medal.”

Coxless pair (5th out of 13)

The pair faced the same draw structure as the double, but unlike them avoided the repechage by coming second in their first round heat of five crews, finishing a comfortable nine seconds ahead of third place.

In the semi-final they jumped start and were called back. “Then, after the re-start they… remained in touch [with Canada in the next lane] for 1,000m until the Canadians powered away to leave the British pair four seconds adrift in second place,” the journalist Chris Dodd claimed, rather strangely implying with the word “adrift” that coming second was some sort of failure, when actually they only needed to finish in the first three. Mike Rosewell, interpreted their race quite differently, observing that they, “Achieved a better rhythm than in their heat, letting the Canadian World Champions lead the race and sitting on a length over the [Bulgarians].”

They finished fifth in the final, after holding that position throughout the race, crossing the line nine seconds behind the bronze medallists.

Pictures of them taken in Banyoles by Peter Spurrier can be seen here. They also raced with cleaver blades.

In the video below the GB pair is in lane 5, second from top of the screen.

Eight (7th out of 8)

The eights started with two heats of four crews from which one would progress straight to the final whilst the others would go to the repechage.

The GB eight came last in their heat, nearly fifteen seconds behind the next crew. The effects of the stomach bug were still lingering, particularly for Philippa Cross, although their result cannot be purely put down to this.

With two clear days until their crucial repechage, they had some time for more training but, Fiona Freckleton noted in her training diary, Philippa was too ill to row, and Bob Michaels decided to rearrange bowside. Kareen Marwick was moved from bow to seven, Kate Grose was put back from seven to five, Dot Blackie from five to three, and Fiona went from three to bow. Fiona says, “I think it was Bob making a change because if you make a change sometimes you get a result, and the heat hadn’t gone well.” Kate, however, felt that she was being blamed by Bob for how the crew had gone in the heat, and Dot simply descries this swapping people around as “a shambles”. A photo of the crew in its new lineup can be seen here.

The repechage was scheduled, Fiona remembers, for 8.50am. “But it was foggy and we actually ended up doing it once the sun had come out at 12.40pm when it was really hot.” She wrote afterwards in her training diary that they we rowed reasonably well until the third 500m section. They finished four seconds down on the last qualifying crew. Fiona passed out after they’d crossed the finish line. “I think it was as much the heat as anything and I wasn’t the only person – they were wheeling people off from a number of crews,” she says; it was reported in the Independent, that Tim Foster, one of the GB men’s eight, whose race was similarly delayed, “Was lifted out of the boat at the finish and held at the medical centre for over an hour.”

The women’s eight was the only GB women’s crew not to have the new big blades; the GB men’s eight switched to them between the heat and the semi-final. (Photo © Maggie Phillips.)

They won the two boat small final by 1.44 seconds from a Czech crew which contained five of their junior team and had been sent to the Olympics for experience. The previous version of the GB eight had been considerably ahead of the Czechs at Lucerne.

Dot Blackie remembers that that they were told that they hadn’t tried hard enough. “I was completely gobsmacked and totally distraught by the whole aftermath while we were still in the village. That was a shock because I couldn’t imagine why anyone would go to the Olympics and not try hard. We might have been a bit rubbish, but I didn’t think anyone in the boat was not pulling, so I found that quite hard to deal with.”

The eight was the only British women’s crew not to use the new cleaver blades at the Olympic games although they had used them at Lucerne. Sue Smith remembers that trying find out how best to row with them was another complication while also adjusting to the new crew line-up, and this may be why they didn’t use them in the end.

Coxless four (8th out of 9)

The four finished last by quite a long way in their first round heat in which the winners, Canada, set a new Olympic best time. They were also last in their four-boat repechage, crossing the line 5.59 seconds behind the second of the two crews which qualified.

In the B final they came second, giving them an overall placing of eighth.

They also used cleaver blades.

From left: Kim Thomas, Gillian Lindsay, Suzanne Kirk and Aggie Barnett. (Photo © Maggie Phillips.)

A photo of them racing, taken by Peter Spurrier, can be seen here.

Single scull (9th out of 15)

Tish’s Olympic regatta started with a first round heat of five scullers in which she finished fourth and so progressed to the repechage the next day. There she came a confident second, which put her into the semi-finals. It was reported in the Independent that, “Reid, who established an advantage soon after the start, appeared to ease up after passing the 1,000m, perhaps mindful of the task ahead.”

Sadly, this didn’t prove enough to help; in the semi-final two days later she crossed the line last, although less than five seconds off qualifying and in a time faster than all three of the non-qualifiers in the other semi.

Third place in the B final put her ninth overall.

Tish after racing. (Photo © Maggie Phillips.)

An excellent photo by Peter Spurrier of Tish racing can be seen here.

Washup

Two fifth places actually at least equalled British women’s best results at the Olympics: the eight and single sculler Beryl Mitchell had also both come fifth in Moscow in 1980, although those Games were boycotted by the USA and Canada, but they were also so much less than everyone had reasonably hoped just a few months earlier. As well, their success and Tish Reid’s solid ninth place out of 15 was despite the squad system rather than because of it; the double and single sculls trained outside the squad system for the whole year, and the pair (when it was Miriam and Fiona) had done that to an extent at least for most of the winter. And as it was the three smallest boats which did best, only these five members of the 19-strong GB women’s team felt that their results were reasonable.