| Years | 2002 World Championships (Lt 2- 1st) |

| Clubs | Southampton University BC, Runcorn RC, Mortlake Anglian and Alpha BC, Upper Thames RC |

| Height | 5’6.5″ or 169cm |

| Born | 1968 |

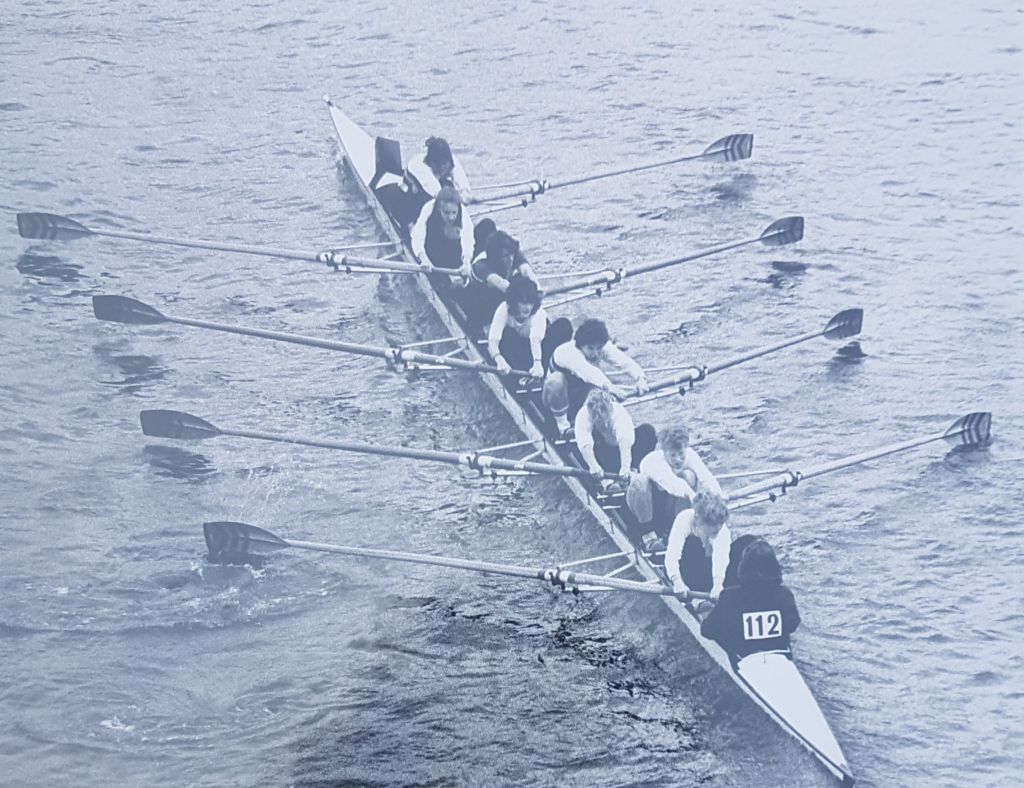

The photo at the top of this page shows Naomi winning the lightweight single sculls at the National Championships in 1995. (Photo: Naomi Ashcroft’s personal collection.)

Getting into rowing

Despite not being allowed to take part in a junior school sports day school because she ‘wasn’t good enough,’ Naomi became an athletic and competitive teenager. Somewhat unusually amongst rowers, she was good at ball games, and particularly enjoyed hockey (playing at club and county level at senior school, and returning to the sport in 2012), netball and rounders. The theme here, she says, is that she liked team sports, a point that will become relevant much later.

Having been inspired by watching the Boat Race on Grandstand, she took up rowing when she went to Southampton University in 1986. Although she chose Southampton for its civil engineering course, she admits that she did check it had a boat club before applying.

Her very first contact with the boat club was a bit inauspicious, though. “I turned up at their stand at the freshers fair, and announced I’d like to join,” she remembers. “The person at the stand replied, ‘What, to cox?’ I put them right on that straight away!” [Note: Despite later becoming an expert bow steers and remaining slim, she has rarely been known to cox since her student days – Ed.]

Naomi describes the first 15 years of her rowing career as a rollercoaster ride with plenty of memorable highs interspersed with equally memorable lows. “Whilst ‘training to win’ fits my competitive nature, on reflection, I certainly learnt more from the harsh lessons of failure, to put it bluntly,” she says. “But thanks to support from coaches and crew mates alike I always managed to bounce back stronger. It was all part of what turned out to be quite a long ‘journey’!”

Her rowing career certainly didn’t get off to the most auspicious start and she recalls that her novice coxed four (which included future Olympic silver medallist Guin Batten) lost all of their races in her first year. “The only race we did win, at Reading Amateur Regatta, we were promptly disqualified from for our steering. Guin and I still have a laugh about this now. Regardless, I’d caught the ‘rowing bug’ and thrived on the team training environment and the early morning outings on the River Itchen.”

Meanwhile, Naomi looked on as the University’s top women’s crew (which included Guin’s sister Miriam Batten, then in her final year) achieved much success under Pete Proudley . “Pete was only allocated to coaching the top women’s crew, but all the senior rowers left in the summer of 1987 so the four remaining novices, of whom I was one, automatically became the first four that autumn. We were delighted, as this meant we started being coached by Pete.”

Her first win was one of the significant highs of her career; Women’s Novice Restricted at the Head of the River Fours in November 1987. Impressively, under Pete’s guidance, Southampton also won the Novice event at the Women’s Eights Head of the River the following spring in a crew that combined Naomi’s four with four freshers who had only been rowing for a few months.

“A combination of Pete’s coaching prowess, passion and our raw talent and enthusiasm (mostly enthusiasm) launched not only my rowing career but many others,” Naomi reflects. “He taught us how hard we could push ourselves and gave us the ability to realise our rowing potential. Pete opened doors for me and introduced me to other very talented coaches including Rosie Mayglothling and Mike Jones. He supported me throughout my rowing career.”

Naomi went on to enjoy a string of wins at University, in both ‘fine’ racing boats and coastal fours. “Pete was instrumental in arranging for the university to race on the coast, and it was great fun,” she remembers. They won the coastal event at the National Championships in 1990, in what remains one of her closest and most exciting races. “We won by just 33/100ths of a second from Shanklin RC.” Although all of her university rowing was done in sweep boats, Pete Proudley wisely advised her that she should learn to scull before she left if she wanted to take her rowing further, and taught her to do so in her final year at Southampton.

The long, long journey to GB selection

Having secured her first job as a civil engineer in Cambridge, where she found sculling challenging because of the narrowness and bendiness of the river and the density of student crews on it, Naomi’s rowing received an apparently improbable boost when she was seconded to work in Liverpool at the start of 1991. She joined Runcorn Rowing Club where the facilities were basic but, crucially, she found the perfect training partner in lightweight international Helen Mangan, and excellent coaching from Mike Jones. “Moving up to Runcorn was the best thing I could have done because I suddenly had Helen to aspire to. Mike took me under his wing and coached me from a novice to a reasonably accomplished single sculler. It did mean that I spent the next seven years being washed down by Helen though,” she reflects. It was here that Naomi met Rosie Mayglothling, a former international who was now working in a development role in Sheffield, and had also coached Helen’s crew lightweight double at the 1990 World Championships. “Rosie brought together a whole group of us from different various rowing clubs in the north west to combine and develop potential, and to challenge the bigger rowing clubs in the south. That’s how I met Juliet Machan from Chester for the first time, and Sophie Clift (Hollingworth Lake), Mandy Calvert from Agecroft, and Janet Vickers, Ali Sanders and others from Sheffield. It was a fantastic training and competitive environment.”

Aware that two Southampton alumna had gone on to row for Great Britain including Miriam Batten, in the summer of 1990, and before that Katie Brownlow, Naomi had already decided that she wanted to take her rowing at least to the level of winning at the National Championships in a ‘fine’ boat, and had aspirations for the GB team.

Naomi’s rowing career followed a lot of ups and downs over the next 12 years as she pursued those goals. Focusing on her single out of necessity, she notched up a string of wins over the next couple of years, of which the most notable was the Senior 1 pennant at the Scullers’ Head in 1992. Although this is one of the achievemets she’s proudest of, in fact, she explains, it was actually the outcome of a significant setback. “I’d not been selected for the North West eight for the Women’s Head,” she explains, “So I decided to focus on the Scullers’ Head which was the next big race – it was in the spring back then.” That summer, she finished fourth in lightweight single sculls at the National Championships, which was an excellent result from a field of 22 entries. That autumn she won the Head of the River Fours in a lightweight quad with Helen Mangan, Trisha Corless and Janet Vickers.

The following year, 1993, she was the second woman at the Scullers’ Head (although she attributes this at least partly to having a late start number, sticking to the stream, and benefiting from the appalling conditions having calmed down somewhat by then) and won at the National Championships. This was enough for her to be selected as the England lightweight sculler for the Home Countries match, which she also won. She went to GB trials for the first time, too, and although not in contention for the team, raced at Duisburg in her single (largely thanks, she feels, to the fact that Helen Mangan was racing there in a double, coached by Rosie Mayglothling, so she was ‘allowed’ to enter too), and also at Paris where she came third. While that regatta wasn’t a first class international event, this was nevertheless one of her best results until that point.

Her rowing career moved on again in 1994 when she finished sixth in the lightweight sculls at GB final trials and, after winning lightweight doubles with Mandy Calvert at Ghent (as well as coming second in open doubles) and Henley Women’s Regatta, where they also won open quads with Janet Vickers and Ali Sanders, was selected to race in the open quads for England at the Commonwealth Regatta in London, Ontario.

Not even this selection went smoothly; Naomi’s ‘selected’ Commonwealth quad was narrowly beaten at the National Championship’s by a composite crew of Juliet Machan, Nikki Dale, Lisa Eyre and Hellen Newport, before flying out to Canada. “Oh, and that composite quad held the course record for several years, as Juliet often reminds me,” she says wryly.

Naomi and Mandy’s lightweight double did, however, remain unbeaten at the Nationals.

Having once again not quite made the GB squad in 1995 – finishing seventh at final trials – Naomi’s biggest win of that year was beating Mandy by what she remembers as a length but the records show as 0.37 seconds at the National Championships. Once again, this selected her as the England lightweight sculler for Home Countries, where she secured her second win.

The top GB women’s lightweight crew, both then and now, is the double scull, because it’s the only Olympic-class boat. So, while GB trials were initially in singles, the coaches also needed to identify the fastest combinations in doubles. Team-player Naomi (remember that early preference?) says, “My problem was that I could make doubles go fast, but I couldn’t make my single fast enough to put me into a position where I was invited to seat race for the double or even the quad, or at least seat race against the fastest lightweights.” So near, but yet so far.

Naomi was actually invited to take part in some doubles seat racing in late 1995, and recorded in her training diary that these were close, but her results weren’t enough for her to be invited to subsequent trials and her rowing took somewhat of a back seat for the remainder of that season as she focused on her chartered engineering exams. In the end, the selected GB lightweight women’s double didn’t qualify for the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta.

Realising that she had progressed as far in rowing as she was likely to while still based in the north west, in the late summer of 1997 Naomi got a new job in London and joined Mortlake Anglian and Alpha BC, which was then the most popular club for women’s lightweights on the Tideway.

Deciding that the Tideway was not the best water to train on, in 1998 she moved to Henley and joined Upper Thames RC where she had a thoroughly enjoyable and successful season. “There was a really good group of lightweight there, coached by James McLean with assistance from Tony Reynolds. I won lightweight doubles at Henley Women’s and the National Championships with Becks Ingledew, and we also won the lightweight quads at Henley Women’s with Vic Wood and Clare Broome. By this point, aged 30, she reflects that she still wanted to row for Great Britain although admits that her ambition “wasn’t burning quite so bright”.

The next year, 1999, after not quite making the cut again at GB trials, she more or less repeated these results, but with Helen Casey replacing Clare in the quad, which was then selected as the England crew for Naomi’s second Commonwealth Regatta in Canada. Their last race before leaving the UK was the National Championships where, embarrassingly, they were once again pipped to the gold medal. “Because you’re the selected crewc you become the target. We were also in the middle of a heavy training programme, focused on the Commonwealth Regatta so didn’t wind down fully,” she explains, adding, “But our boat was already on the way to Canada by then, so we got away with it.” After invaluable coaching input from Rosie Mayglothling, they were happy to finish only four seconds behind Canada and to win the silver medal.

Naomi continued to trial unsuccessfully for GB for the next two years while enjoying considerable success at top domestic events with Upper Thames. Notable achievements included qualifying for the first open women’s eights event at Henley Royal Regatta in 2000 (where she beat the author’s crew in the first round, in the rain, very early on the Saturday morning); winning the gold medal at the National Championships with the same crew; and winning lightweight quads again at Henley Women’s Regatta in 2001.

International rowing career

In the autumn of 2001, aged 33, she realised that she needed to change something or she was never going to make the GB team. Key to this was Filipe Salbany, who had recently started coaching at Upper Thames. “He agreed to take me on,” Naomi explains. “He changed my training programme a bit, but the main difference was technical. I can remember him telling me that I’d probably go slower to start with before I became faster because we completely broke my stroke down and started from scratch.”

She also sought psychological input from Kirsten Barnes, a former Canadian Olympic champion who was then based in Henley. “I used to become so nervoud when I was competing,” she says, “So Kirsten taught me just to focus on the process itself and the first time that really worked was at the British Indoor Championships in November, which were a breakthrough for me both physically and mentally. Filipe’s coaching supplemented by Kirsten’s support gave me the confidence to achieve a PB [personal best] and beat both Jo Nitsch and Tracy Langlands (two of the top GB lightweights) in the process. I was actually so focused on my PB and my time, beating them was almost incidental, but very satisfying!” Naomi’s time was 7.11.

She made the most of her new mastery of the rowing machine by travelling to Boston, USA to compete at the ‘CRASH-B’ World Indoor Rowing Championships the next February where her time of 7.15 placed her second in the masters openweight category and won her one of the event’s famous hammer trophies as fastest masters lightweight. Only a very few will appreciate why it’s worth travelling over 3,000 miles to spend less than eight minutes on a rowing machine to win a shiny household tool.

Despite this considerable transformation, Naomi’s year plunged downhill again when she failed to be selected for any of the seven sculling places on offer. “But I’d done enough to start pairing with Ali Eastman, with the expectation that we might be the GB lightweight pair,” she remembers. [Note: the pair was considered the least prestigious of the four international women’s lightweight events behind the quad, double and single sculls because there were no sweep events for lightweight women in the Olympic programme – Ed].

Alongside this, Naomi was determined to race her single at Henley Women’s Regatta to show the squad coaches that she could be competitive. She duly won the event, which had attracted a massive entry of 26. “If my season had finished at that point, I would have been ecstatic really. I love Henley Women’s Regatta and to win the lightweight single with my family and many friends there supporting me was very special, especially as I’d beaten Helen Mangan in the third round, so the tables had finally turned there,” she laughs now.

But the rollercoaster was about to hurtle headlong into yet another trough. After Henley Women’s, Ali and Naomi focused on their pair for four weeks before racing at the National Championships as the GB crew-elect. Being beaten by 0.69 seconds was not part of the plan, though. As their boat wasn’t already en route to the event on this occasion, fresh seat racing was arranged at Dorney with Jo Ganley and Leonie Barron, the Thames RC crew who had got the better of them. As they were trialling for a sweep boat, and each woman only rowed on one side, this pitched Ali against Leonie and Naomi against Jo. “I remember receiving a stern talking-to from Juliet Machan the day before, who convinced me I was good enough in a pair to do what I had to do,” Naomi recalls. Juliet was right. “I won on bowside by nine seconds, and Leonie beat Ali,” she adds.

The new combination then raced at teh World Cup III regatta in Munich a week later, where they won comfortably in a straight final against three other crews from Hungary, Spain and China. “It was hilarious because we weren’t at all good when we were paddling, but so long as we were going firm and rating about 34, we were fine,” she remembers. “I knew we were fast as soon as I got into the boat with Leonie and we did some race pace pieces. It flew.”

After that, as the World Championships weren’t until the second half of September (to avoid the worst of the summer heat in Seville), they had a little more time to blend as a unit, training at Dorney and then at the pre-Worlds training camp in Varese with coach Pete Sudbury, about whom she says, “Managing two lightweight women going to their first World Championships was quite a feat, particularly in a pair which is a technically demanding boat to row. We spent a lot of time workin on technique in an indoor rowing tank, which did pay dividends.” So far so good, but was it going to be a straight run up to the top of the ride from here?

There were only four entries in the women’s lightweight pairs that year, which meant their race would be a straight final, and without even a race for lanes, it was decided, quite reasonably, that they should do a full dress-rehearsal on the course (in GB race kit) during a practice session between blocks of racing. During these, a ‘circulation pattern’ is set out which is designed to group boats of similar speeds into different lanes to avoid overtaking. This means that eights can only use one lane, fours and quads another, pairs and doubles another, and singles another.

So that was the situation, and here’s what happened. “I was steering and I was worried about going in the lane for pairs and doubles, in case a men’s double came up behind us,” Naomi explains. “When we got to the start, there weren’t any scullers in the singles’ lane, so I decided I’d use that because we wouldn’t be in anyone’s way and there was less chance of us having to stop if we were being overtaken. So we went for it, but after about 750m, a safety marshal came alongside in his launch and said, ‘Great Britain move lanes, Great Britain move lanes.’ I thought that they might award us a false start if I didn’t move, so I crossed through the buoy line but Leonie’s blade caught a buoy and then we found ourselves upside down in the middle of the lake with various pairs and doubles bearing down on us. Thankfully, the original safety marshal was there to rescue us! We had to go back and complete our 2k piece in the evening.”

Their race was scheduled for the final day of the World Championships, which left plenty of time for nerves to build. “I’d always envisaged that if I were to get selected, I’d be in a crew with some experienced GB athletes and, of course, neither of us were – we were very much novices at this international level,” she recalls.

Both Naomi and Leonie were so far from being full-time athletes that they were just taking annual leave from their day jobs to compete. “I was working in Flood Risk Management at the Environment Agency at the time but thankfully I had a very supportive team, who were almost as excited as me, that I had finally been selected.”

“I found waiting for the final excruciating. A combination of winding down, the race build up and generally feeling terrified resulted in my body feeling like it wanted to shut down, as opposed to that ‘raring to race’ feeling”. I found myself quite emotional when I thought about the race and the enormity of it for me personally, particularly as we were going in as favourites after our Munich result.”

However, Naomi drew on what she’d learned from Kirsten, focused on the process, and together Naomi and Leonie found the rhythm that Pete Sudbury had drilled into their rowing to duly deliver the gold medal that the GB team so needed, winning by 11.2 seconds. “We did 7.25 in our practice row, and 7.29 in the final,” Naomi notes, “Because that’s all we needed to do to win. There was certainly no need to take any risks with the lead we had and I definitely didn’t want to be hitting any buoys. As I said after the race, that win was the ‘gold at the end of the rainbow’. It was the culmination of many years of training, trialling and heartache, not just for me, but for all my coaches, rowing friends and family. I wrote ‘Very VERY relieved’ in my training diary.”

A full account of the GB women’s rowing team’s 2002 season can be read here.

Naomi and Leonie trialled again in 2003 with the aim of being selected in the pair again, but were beaten at final trials by another crew put together by the GB coaches. “We raced at Henley Women’s in openweight pairs but Leonie was ill and we lost in the final,” she says. Neither rowed for GB again, each retiring with an unbeaten World Cup and World Championships record, the only British women to achieve this distinction.

Later rowing

Naomi’s rowing career is symmetrical in that the length of her run up to brief but glorious international representation has been matched by a long, ongoing and very successful time rowing since then.

She reached the semi-finals of the Princess Royal Challenge Cup at Henley Royal Regatta in 2003. “That performance stemed from the single sculling that I’d started with Filipe the year before. And that was a massive achievement for me because I was beating openweights,” she reflects. “I remember being down off the start in both the heat and the quarter final, which is what I expected as a lightweight, but then I’d drop the rate to 33, find some free speed, and scull through my opposition whilst under-rating them. I don’t think I’ve ever gone as fast in my single since!”

Naomi also won lightweight doubles at the National Championships with Becks Ingledew again two weeks later. They went on to win the lightweight pairs at Henley Women’s in 2006. Coached by Guin Batten, she feels this is one of their greatest achievements as they took on the challenge of racing a pair and coming back from earlier defeats in the season to a younger Scottish composite pair whom they beat in the final. They then won the lightweight doubles in 2007, coached by Clare Broome and Helen Mangan. These victories along with a win in Elite (Openweight) Quads in a composite crew in 2005 brought her total haul of Henley Women’s medals to 11, all of them from Championship events. This puts her equal with Sue Appelboom (who won the women’s lightweight single sculls for ten consecutive years) as the most decorated Henley Women’s medallists.

Impressively, Naomi has continued to race at the regatta, most recently in the lightweight doubles with Becks (now Sadler) in 2019, some 30 years after her first appearance there. Her final appearance at Henley Royal Regatta was in 2008 when her largely lightweight quad reached the final of the Prince Grace Challenge Cup in torrential rain; although they didn’t win, they had become the first Upper Thames crew to reach a Henley Royal final.

Naomi puts some of her rowing “longevity” down to her special rowing and sculling partnership with Becks from 1998, during which time they have won seven Henley Women’s titles and two National Championships gold medals, and continue to race successfully at Masters level, now in their 25th season together.

“We are both passionate about wanting to make the boat go faster, but often have different opinions as to how to achieve this which livens up the partnership. Becks sets a great rhythm to allow us to apply our power (what’s left) together and alongside our competitive nature, trust in each other and ability to perform under pressure we have enjoyed, quite simply, a precious harmony on the water.”

In 2016 Naomi and five other largely lightweight women (including the author), broke the Guinness World Record for the greatest distance rowed in 24 hours by a women’s team. That same year she won the bronze medal in Women’s Grand Master’s Eights at the Head of the Charles regatta against stiff opposition, and in 2017 her Upper Thames group won the Victrix Ludorum trophy at the World Masters Regatta in Bled.

“After all these years I still believe that rowing is the ultimate team sport and I love the feeling when crews come together to achieve much more than just the sum of the individual parts,” she concludes.

Off the water, she has been been Secretary and Safety Officer to the Upper Thames RC committee. She served as Secretary of Henley Women’s Regatta till 2011 and was Head of Ceremonies for 15 years till 2022. Retirement from the committee proved short-lived, though, when she took on the Chairmanship in late 2023 after the post became unexpectedly vacant.

Away from rowing she has cycled from Lands End to John O’Groats, completed the Raid Pyreneen, several stages of the Tour de France (finishing with an ascent of Mont Ventoux), the Henley Challenge Ironman triathlon (just), run three London Marathons, taken part in the Henley Swim, and been top goal-scorer for her local hockey team for several seasons.

Many of her friends consider her as exhausting as she is impressive.

© Helena Smalman-Smith, 2023.