FISA

Le Fédération Internationale des Sociétés d’Aviron or FISA (the governing body of international rowing) passed its first resolution regarding women’s international regattas at its Ordinary Congress on 30 August 1950.

In a masterful example of the “listening but ignoring” approach, FISA President Gaston Mullegg noted the objections from some countries (Switzerland was against women sculling in anything other than a single, and Italy was against them racing in anything at all), and dismissed suggestions that women’s international competition should involve a mix of racing and style competitions on the grounds that women wouldn’t find this acceptable.

He then swiftly moved the agenda on to practical details where the congress could more easily make decisions, which they duly did, voting accepting a proposal that women should race in singles, doubles, coxed fours and eights, and that the distance should be 1,000m. Exasperatingly, the reasons for this unanimous choice of distance were not recorded.

The following year, on the eve of the first FISA-approved international women’s regatta (so, prior to this demonstrating that women’ rowing was actually worthy of being taken seriously), The FISA Centenary Book records, “Congress, by an overwhelming majority, agreed that international regattas for women should be held each year under the auspices of FISA, if possible as part of the European championships, either on the day before them or after them [they were never actually held after], but on no account during the actual championships.”

FISA clearly wanted women’s international rowing to work and the running of international regattas in conjunction with European Championships could only mean that it expected there to be full Women’s European Championships in due course, but as with almost all its events and innovations, it took the perfectly reasonable approach of establishing unofficially that the idea was definitely viable before it was adopted. This should not be interpreted as ‘sexism’ but as the type of due diligence that is proper for a world governing body: the same happened with introduction of Championships for juniors and lightweights.

Three international regattas – which might today be described as test events – were run to prove the concept. These took place in Macon (1951), Amsterdam (1952) and Copenhagen (1953).

In a further indication that FISA was entirely behind women’s rowing, and again before the last of the test events took place, FISA accepted a proposal by France and Holland at an Extraordinary Congress on 27-30 May 1953 to run Women’s European Rowing Championships starting in 1954.

The FISA Centenary Book adds that, “These championships would not necessarily be organised by the country that was organising the men’s championships,” although there were only actually two occasions in the twenty-year life of the Women’s European Championships when the men’s event took place somewhere different from the women’s. On both of these, the women’s championships were in Eastern bloc strongholds of women’s rowing (Romania in 1955 while the men were in Belgium and the USSR in 1963 when the men were in Denmark), suggesting that the reason for having them in different countries was more to do with the enthusiasm of Romania and the USSR to run women’s showcase events than any disinclination by the countries hosting the men’s events to incorporate women’s racing. That said, one of the women in the GB team in the 1960s remembers a rumour that undefined “poor behaviour” by some of the Dutch women at the 1953 regatta in Copenhagen had led the Danish federation to refuse to host women’s events again.

Macon 1951

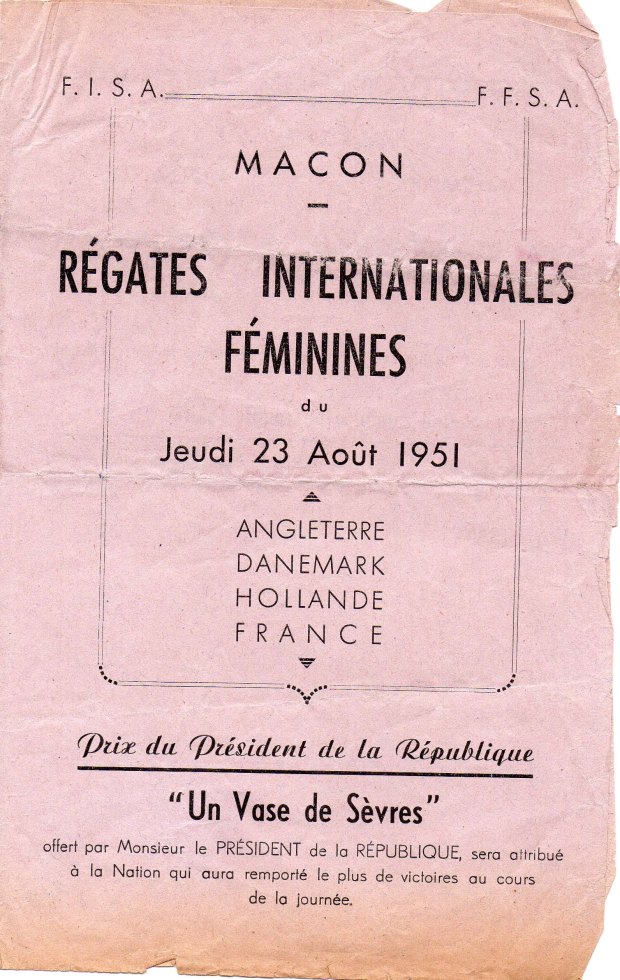

The first FISA event for women was held at Macon on 23 August 1951, the day before the men’s European Rowing Championships began. It was organised by the Federation Francaise de Societés d’Aviron and, as the Women’s Amateur Rowing Association reported in the British Rowing Almanack, “In promoting this regatta, the primary aim of the FFSA was to help the fight for the inclusion of women’s events in the European Championships,” although the minutes of FISA Congresses recorded in The FISA Centenary Book suggest that a “fight” wasn’t needed at all, just an evidence-based proposal.

The FFSA and the WARA – which had developed a close relationship because one of the leading lights of the FFSA, Suzanne Caverhill, was a Frenchwoman married to a Scotsman – had probably been the most active national federations in lobbying FISA about running international women’s events. The fact that the Championships were taking place in France anyway gave the FFSA the perfect opportunity “to give proof of the standard of women’s rowing in Europe and show the strength of their claims for the inclusion of women’s events,” as Hazel Freestone, the WARA’s Secretary, put it in Rowing magazine.

The event offered just four events – eights, coxed fours, double sculls and single sculls – and attracted entries from just four countries – France, Great Britain, Holland (as Brits called it at the time) and Denmark (no Eastern bloc countries, you note). The Women’s Amateur Rowing Association decided to support the event by entering every category, and went through a relatively rigorous procedure to choose the crews.

Eight

The four WARA Selectors (Amy Gentry, Eleanor Lester, Margaret Barff and Gladys Barnes) watched five different eights races and came to the conclusion that:

- The best club crew was the University of London Women’s BC.

- A ‘representative’ crew made up of the best club oarswomen might be faster.

Given that the GB men’s team was invariably made up of club crews at this time, this was actually quite radical thinking.

As the ULWBC eight wanted to stay together, the selectors held trials on 3 June (ironically, at the UL boathouse) and picked the following eight which trained together and then beat the ULWBC crew decisively in a trial on 29 June:

B: Shirley Radley (Borough of Hackney Ladies RC)

2: Pauline Grudgings (Civil Service HQ Ladies RC)

3: Jane Barlow (Civil Service HQ Ladies RC)

4: Ann Hewitt (Borough of Hackney Ladies RC)

5: Grace Harvey (Alpha Women’s RC) – Captain

6: Eve Bailey (St George’s Ladies RC)

7: Julie Johnson (St George’s Ladies RC)

S: Eileen McNally (United Universities Women’s BC)

Cox: Barbara Bagwell (United Universities Women’s BC)

This was the first women’s eight from Britain to compete abroad.

Note the Tudor roses on the crew’s shirts. (Photo: British Rowing archive.)

Coxed four

This was put together from those who had not made it into the eight, plus others who had not been able to attend those trials. For the record, the selectors recognised that there was a particularly promising Edinburgh University crew, which had done well at the University Women’s Rowing Association regatta, but transport logistics mean that this group was unable to get involved. Given that the crews actually raced as ‘England’ and not Great Britain (with red roses on their shirts not Union Jacks), this conveniently avoided what might otherwise have been a constitutional difficulty.

B: Joyce Carter (Weybridge Ladies ARC)

2: Sylvia Harper (Weybridge Ladies ARC)

3: Ada Marsh (Stuart Ladies BC)

S: Joyce Townsend (Stuart Ladies BC)

Cox: Barbara Bagwell (United Universities Women’s BC)

The crew used new oars – costing £7 each – that belonged to Weybridge Ladies and had been financed by a loan from another member of the club.

Double scull

The double scull of Irene Helps and Pam Body from Alpha Women’s ARC was selected as crew and were coached by Irene’s father, Jack, a notable sculler.

Pam and Irene in Macon with Irene’s father Jack Helps. (Photo: Christina Forey’s personal collection.)

Single scull

Marjorie Townsend from Stuart Ladies BC was the single sculler, although her selection came quite late because the Selectors couldn’t decide between her and fellow River Lea sculler Betty Clark of Borough of Hackney LRC. Betty eventually withdrew because of back trouble, making the issue moot.

Marjorie Townsend sculling in 1951 although not actually at the Macon event. (Photo: Barbara Kaye’s personal collection.)

The Stuart Ladies members had done well to get back to training at this level after a tragic accident in April when a drifting barge had crushed their eight whilst they were out training, killing one of their crew, Jean Walton, despite the best efforts of Marjorie’s fiancé, Ronnie Lutz, a well known oarsman, who was coxing them at the time.

Getting there

At the planning stage, it was estimated that attending the regatta would cost the WARA at least £50, which they didn’t have. An appeal was made – understandably unsuccessfully – to the 30 or so affiliated clubs, for funds. In the end, the FFSE paid for competitors’ travel from the French coast, and an anonymous donor gave the WARA a cheque (which actually meant she or he wasn’t truly anonymous, but credit to Amy Gentry for not spilling the beans – the Association’s President, Lady Desborough, is a likely candidate though) which enabled the team to fly to Paris, saving them a draining overnight train-boat-train journey, and for their blades and Marjorie Townsend’s scull to be sent to Macon.

At the Championships

After arriving on the Wednesday morning, the British crews quickly got to grips with the boats they were lent. With men afloat too – practicing for the European Championships – the women enjoyed being “in this centre of bustling rowing activity” as Irene Helps put it later in Rowing.

The England women’s team at Macon. (Photo: Rowing magazine.)

All of the English entries came third in the races on the Thursday afternoon. In the case of the double, this also meant last, but the other three events each had four entries. The eight had apparently gone off rating 42, which was exceptionally high for the time.

Amy Gentry, Chairman of the WARA, was the British delegate at the regatta and reported in The Oarswoman how impressed she was with the “outstanding” Dutch eight who had apparently been training for the race for two years. But she added that she had heard at the regatta that thousands of women were rowing in both Denmark and Holland compared with the 400 or so oarswomen in Britain (although it’s possible that the type of rowing these thousands engaged in might not have been exclusively ‘fine’ racing boats).

With a Sèvres vase on offer to the nation with the greatest number of wins, this was arguably the best-rewarded women’ regatta ever. It’s unclear whether the French managed to keep their piece of porcelain or whether the Dutch took it home as both countries scored two wins across the four events.

The crews all stayed on to watch the men’s Championships, making the most of the French hospitality and having a grand time getting to know the other women competitors. Wine was involved.

Amsterdam 1952

As in 1951, the Women’s International Rowing Events in 1952 were only contested by Britain, France, Holland and Denmark.

After the decision in 1951 to produce a ‘representative’ eight and four from the best available British oarswomen, the WARA’s selection policy swung back towards club crews (a pattern to be repeated again and again in British international rowing, really until the National Lottery funding arrived in 1997) because “the difficulties of trying to build a composite crew were too numerous” (The Oarswoman). As Amy Gentry had observed in a retrospective on the 1951 Macon regatta in Rowing, the major advantages of selecting club crews – in addition to basic training venue convenience – were that there should be more uniformity of style (this was a time when different clubs had very different techniques) and that clubs’ own programmes would not be disrupted. Her vision was that the whole standard of British women’s club rowing be raised so that the best club crews would be competitive internationally. This was a perfectly reasonable strategy when racing Western European countries which also fielded club crews, but it would prove totally inappropriate later when Eastern bloc countries were involved, with their state-sponsored rowing programmes, of course. But that’s a matter for later.

Back to the point, in 1952 Stuart Ladies BC were selected in the eight (shown in the photo at the top of this page), and Reading University in the coxed four:

| Eight | Coxed Four | ||

| Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

Doris Williams Barbara Benzing Ada Marsh Rene Plumer Bette Shubrook Ann Hewitt Marjorie Townsend Joyce Townsend Doreen Cann |

Bow 2 3 Stroke Cox |

Shirley Campbell Margaret Peach Pamela Arman Marie Lakeman Maureen Bywaters |

Four members of the eight – Ada, Ann, Joyce and Marjorie – had also competed at the international regatta in Macon in 1951.

We didn’t send a double or single sculler this time.

A rare colour photo of the Stuart Ladies crew. Their pale blue shorts had white and navy stripes down the side – their club colours. (Photo: Barbara Kaye’s personal collection.)

Results

After a strong row and a superbly timed finishing ‘spurt’ (as it was always called in those days), the Stuart Ladies eight won by second from the Leiden University crew representing Holland. The French were considerably further back in this three-boat race. As Barbara Benzing remembers it, the British crew were in a heavy, borrowed, clinker boat whilst the Dutch had their own racing shell, making the victory all the more impressive.

The Stuart Ladies eight wins for Britain by one second from Leiden (foreground). The cones and balls overhead indicate the lanes (which were not then marked by buoy lines), which probably explains why the two crews are so far apart sideways in a three-boat race. (Photo: Barbara Kaye’s personal collection.)

The Reading University coxed four came fourth out of four.

Winning crews were presented with bouquets of flowers straight after the race, and later with medals.

The winning Stuart Ladies eight with their coach Ronnie Lutz. Although all crews at the regatta were club crews, the British team were the only ones who did not wear a national emblem. According to the Reading University cox, “It was felt that this should be arranged.” (Photo: Barbara Kaye’s personal collection.)

In terms of convincing FISA that women’s racing merited a European Championships, it was looking good, or as Barbara Benzing put it, “That’s how they allowed us to get in – because we showed that it was possible.”

With wonderful optimism, Maureen Bywaters, the Reading University cox, wrote in The Oarswoman that, “The next FISA meeting is at Copenhagen in 1953 and as it will then have been in France, Holland and Denmark, there is always the possibility of an international regatta in England in 1954. We must not lose sight of this, and everyone must aim for better international standards so that the Cinderella of women’s sports, namely rowing, will be included in the Olympics of 1956.” Only 20 years too early, but ‘daring to believe’ like this was an important element in finally bringing women’s rowing to the Olympics in 1976.

Copenhagen 1953

Judith Franklin’s pin from the Copenhagen Championships.

This took place on 13 August 1953 and attracted entries from Norway, Finland, Austria, (West) Germany and Poland as well as the usual four of Great Britain, France, Holland and Denmark.

Although the WARA Selectors had announced in the April 1953 issue of The Oarswoman that “in all probability the best club eight and four will be chosen”, in the end, only an eight – from the University of London Women’s BC – was sent:

B: Mavis Hammond

2: Barbara Philipson

3: Gill Perry

4: Mary Canvin

5: Alfreda Dannell

6: Frances Bigg

7: Judith Franklin

S: Shirley Bull

Cox: Sheila Allison

UL’s selection followed a less-than-impressive start to their season when they could only manage third place in the 12-boat Women’s Head of the River Race behind Stuart Ladies and Alpha. However, their result was badly impacted by having done too much training in the week running up to the event as Frances Bigg noted:

[The race] was on the first Saturday of term so we came back a few days early. We did courses on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday with Mike Paye [a coach from Vesta RC] – Wednesday’s was quite good – and then courses on Thursday and Friday with Dicky [Franckeiss].

When Saturday came we felt leaden! We were jolly lucky to stay third.

By the time the Women’s ARA Eights regatta came around two weeks later on 9 May, they’d got their training periodicity sorted and beat Stuart Ladies “for the first time,” Frances noted, adding that her crew rated “28 to their 40 all the way.”

As exams prevented the students from competing at the Coronation Cup the following weekend or the Borne Cup Eights the weekend after that, the Selectors quite reasonably announced that selection trials needed to be help.

UL, Alpha and St George’s all put themselves forward for these trials, which took place on the fairly straight 1,000m Desborough Cup in Weybridge on the first Saturday in July. Rather charmingly, Frances recorded that the course was from, “The chestnut to the bridge,” before describing the results:

We won the first from Alpha with St George’s trailing.

We won the second by a length from Alpha and a few feet from St George’s who we had not seen (except bow and two) creeping up at the end – bow and two nearly pulled the bows off the boat.

As this was the required two thirds wins we did not have to race again.

At some point after their selection they were visited by a reporter whose piece on them in an unidentified newspaper was typical of the times, including as it does several lines that younger readers should note, just so they are aware that when they see relevant fact-based articles about women’s sport today, it wasn’t always this way:

Eight trim, white-clad London girl students had a final rowing practice on the Thames today. They are to represent Britain in the Women’s International Regatta on a lake near Copenhagen next Thursday.

The girls, forming the University of London women’s eights crew will be Britain’s only crew in the Regatta.

Training has been strict culminating with two practice spins a day this week.

The rules have been stringent too – no smoking, no drinking, early nights, muscle-building food with a strict limit on cream buns and cups of tea. Boy friends? “We haven’t got time for them anyway,” say the crew.

To give the article the briefest of analyses, it describes women as ‘girls,’ their body-shape and clothing are among the first things it mentions, and it also covers boyfriends. It’s surely unlikely that even then that an article about an equivalent men’s crew would have covered comparable topics or described the oarsmen as ‘boys’.

Getting to Denmark

The journey to the Championships was also not at all how things are today, as Frances recorded with stoical calm:

The selectors had done no booking and passages were almost impossible to get so we had to split. Three of us left 24 hours before the others.

Although we were on the train from Calais (late evening) till Copenhagen (next evening) there was no restaurant car. We had only taken food for the first day so we got hungry. We only had Danish money so we couldn’t buy anything at the stations till we crossed into Denmark (about noon on Saturday) when we bought chocolate and pop.

“Copenhagen here we come! and with high hopes of victory.” From left: Judith Franklin, Frances Bigg, Alfreda Dannell at Victoria station. (Photo: News Chronicle, 8 August 1953 from Judith Costley’s personal collection.)

Other members of the 1953 GB women’s VIII in their formal, travelling outfits including ULWBC blazers. (Photo: Frances Bigg’s personal collection.)

The race

Frances’s calm acceptance non-ideal situations continued into the rowing itself. “The boat we borrowed was very old (though originally good, no doubt) and creaked a lot and needed leather washers to steady the stretcher,” she wrote, adding that “It was choppy on the day of the race.”

They had some opportunity to practice beforehand, and Mike Paye came out and coached them. Interestingly, they were the only crew in the whole regatta to have brought a male coach.

After all of this preparation, they only had a single, three-boat race:

After a tricky start (language trouble) we fought Holland all the way – neither crew rowing frightfully well (splashy) – but they just pipped us on the post, with Denmark easily last. We nearly forgot to collect our silver medals too, which were presented by Princess Louise.

The official verdict was that the British crew were second by 1.4 seconds behind the Dutch but 5.4 seconds ahead of the Danes.

GB come second in the eights at the 1953 International Women’s Regatta in Copenhagen. (Photo: Frances Bigg’s personal collection.)

Judith Franklin’s silver medal. The engraving ‘Otter’ on the bottom of it means ‘Eights’.

The 1953 GB women’s eight. Note that, as did the 1951 crew, they have Tudor roses on their shirts rather than Union Jacks. This photo was taken while they were waiting to be presented with their medals. (Photo: Frances Bigg’s personal collection.)

Judith Franklin’s UL full colours scarf with the England rose for competing at Copenhagen. (Photo © Judith Costley.)

Writing in The Oarswoman soon afterwards, Amy Gentry made balanced remarks about how the Dutch crew might have been slightly better than the one the Stuarts beat in 1952, and how the fact that this year both the Dutch and the British were in borrowed boats, putting them on more level terms equipment-wise.

It’s therefore rather baffling that in an article published in the 1970 British Rowing Almanack, a retrospective entitled ’50 Years in Women’s Rowing,’ she said of the 1953 Copenhagen event, “I would prefer to draw a veil over the race where conditions and officials combined to make a disastrous occasion which left the British party fuming but helpless.” Her veil-drawing was so entirely successful that I can’t find any trace of what she felt was so awful, although Lake Bagsvaerd in Copenhagen does have a dodgy reputation for strong cross-winds and unfair lanes caused by there being shelter on one side of the course. Although she was only 67 when the article was published, and is likely still to have been in full possession of her formidable faculties, she was writing more than 25 years after the event, and memory is a funny old thing.

GB women’s rowing and FISA

In the early 1950s, the Women’s Amateur Rowing Association in Britain was a separate organisation from the Amateur Rowing Association, the governing body with which FISA had hitherto dealt, and so FISA was understandably not keen on having to deal with two separate governing bodies for one country, which was a bit of an issue. However, a simple fudge was put in place in 1952: representatives of both the ARA and the WARA formed a Joint Advisory Committee for International Affairs which provided the single contact point for that FISA wanted, and the problem was solved. The first two delegates who represented women’s rowing on the Joint Advisory Committee were Amy Gentry and Eleanor Lester.