The eleventh Women’s European Rowing Championships took place on the purpose-built Bosbaan course in Amsterdam, as they had ten years earlier, from 31 July to 2 August, shortly before the men’s Championships on 6-9 August.

There were 35 entries from 12 countries which was three crews and one country up on the previous year.

Racing was over 1,000m, the distance set by FISA when it first introduced international women’s rowing in 1951.

A joint poster for the women’s and men’s Championships (from Ann Sayer’s personal collection).

These dates were unusually early for European Championships, but were chosen because of the lead time needed to ship the men’s boats to Tokyo for the Olympic regatta in mid-October (the men’s European Championships were only run in Olympic years when the Olympics were outside Europe).

Selection

The 1964 team had a major injection of new blood for the first time since 1960 in the form of a young four from the University of London Women’s BC.

The crew had a successful season, winning non-status eights at the Lady Fletcher Eights on 2 May, and then senior fours at the WARC Fours Regatta on 13 June, at the WARC Barnes and Mortlake Events on 20 June, and at Weybridge Ladies Regatta on 27 June.

The UL four at Weybridge Ladies Regatta. Note the lady in the dress in the bottom right with the cigarette in her mouth who is trying to hand the finish judge an ice cream just when she is judging a race (although to be fair, it’s not a close one). (Photo: Christine Davies’ personal collection.)

Their final test came at Bedford Ladies Regatta on 11 July where they beat four of the most experienced members of the United Universities group (the exact crew which had competed at the European Championships in 1961, in fact), although only just. UU member Ann Sayer recorded in her training diary that, “UU’s performance put selectors into quandary. UL were very much improved of late, in fact, not recognizable. UU gradually built up half length lead soon after start, hung onto this until c.750 metres then UL began to come back and there was nothing UU could do.” By the end of the day, she reported, the Selectors were still “undecided whether to send UL or not”.

However, one of the crew, Margaret Gladden, who was also Captain of ULWBC had got the support of Freddie Page, according to her crew mate Christine Davies, and she thinks he talked the selectors into giving them a chance, although after the Championships he admitted in the Almanack that the need to start developing new internationals was the only real justification for their selection. As an investment in the future, it paid off, as Margaret Gladden represented GB on five more occasions (including one year 1969 – when she was the entire team – the only time this has ever happened) and her crewmate Christine Davies did another three.

UL (left) draw level with UU at Bedford Ladies regatta. (Photo: Ann Sayer’s personal collection.)

A UU eight – by now described by Freddie Page as “those experienced but ever-eager veterans” – was also selected, despite half of them having been beaten by UL in the four. They had, however, won the WARC Head of the River Race for Eights (nowadays known as the Women’s Eights Head of the River) on 25 April, and non-status eights at the WARC Eights on 9 May, at Alpha WARC Regatta on 23 May and at Walton Regatta on 6 June (one of the first occasions when an event for women was included in an established Thames regatta), so their position as the fastest women’s eight in Britain was not in question.

The Zona Howard/Vivien Roberts double was no longer in training. “I think Viv had had enough, probably,” explains Zona, “She wanted to do other things but I wasn’t quite certain whether I wanted to do other things. I can’t remember why we didn’t go on. I think we’d given it a good shot – three years – in the double and we were still behind and we couldn’t get any coaching and so I think she thought she’d get on [with her career] – she was quite ambitious teaching. But I just wanted to keep up the rowing because I enjoyed it. I don’t think I was finished.” So Zona went back into the eight, replacing Frances Bigg who had stopped rowing seriously at the end of the 1963 season.

The final team was:

| Eight (United Universities) | Coxed Four (University of London) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox Reserve |

Marrian Yates Jill Ferguson Margaret Chinn Ann Sayer Zona Howard Daphne Lane Pauline Baillie Reynolds Barbara Philipson Margaret McKendrick Kathleen Henderson |

Bow 2 3 Stroke Cox Reserve |

Beryl Fox Christine Davies Bridget Pendered Margaret Gladden Mary Mee Sue Hart |

| SINGLE SCULL (LALEHAM SKIFF AND PUNTING CLUB) Penny Chuter |

|||

The eight and the four at the Championships. Back row from left: Marrian Yates, Marg Chinn, Pauline Baillie Reynolds, Ann Sayer, Daphne Lane, Bridget Pendered, Beryl Fox, Christine Davies. Front row from left: Jill Ferguson, Zona Howard, Barbara Philipson. Margaret McKendrick, Mary Mee, Margaret Gladden. (Photo: Christine Davies’ personal collection.)

Preparation

Weights

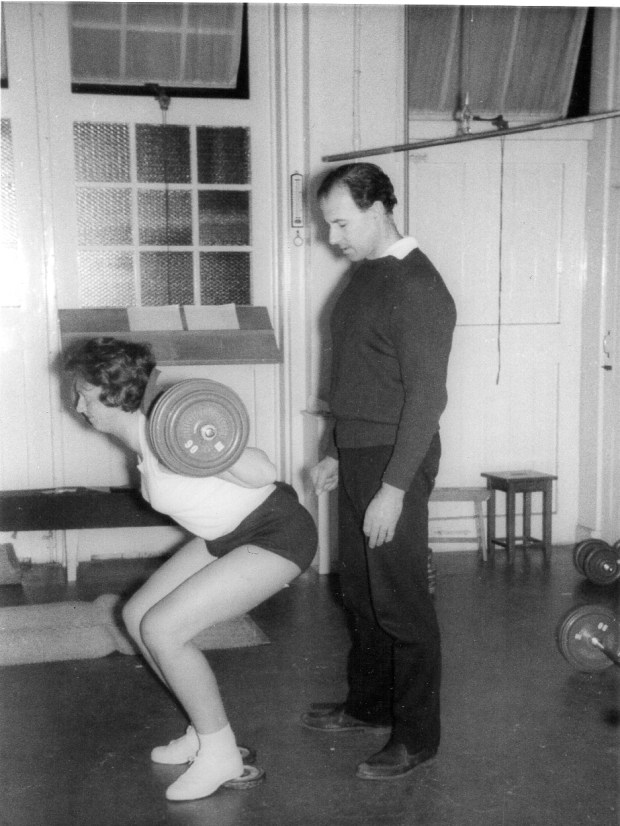

One of the most significant changes that Penny and the UU group made to their training in the winter of 1963/64 was that they started doing heavy weights regularly in addition to their usual circuit training, and based on the oft-proven maxim, “If you keep doing the same thing you’ll keep getting the same results,” this had the potential to be a game-changer.

Of course, this was only the rediscovery of what the Stuart Ladies group had been doing ten years earlier, but this time it stuck and GB women – in fact women rowers of almost all standards in Britain – have done heavy weights ever since. It is a strength endurance sport after all.

In 1963, Penny had been quoted in a Sunday Times article as recognising the need to do weights, but not being able to find suitable facilities anywhere. If this sounds extraordinary today, it’s worth bearing in mind that in 1963 the Amateur Rowing Association had recognised that the whole of Britain’s approach to training (not just in rowing, to be honest) was so out of date that it appointed a non-rowing Director of Training who spent the next several years publishing articles on why weight and circuit training were valuable, how to do them, and what equipment they required (as hardly any clubs had any), as well as visiting clubs to show the uninitiated (i.e. everyone, more or less) what they were.

Anyway, a London RC sculler with a couple of Henley medals to his name called Edward Sturges spotted the story in the paper, got Penny’s phone number from the ARA, and offered to help. After returning from active service in the Second World War, Edward had started a private gym (a revolutionary concept at the time) in Knightsbridge, providing a range of training including classes for children which were attended by the young Prince Charles and Princess Anne, whom Ann Sayer remembers seeing on one occasion leaving discretely with their nanny by the back entrance and weaving their way past the bins and the bike racks! Edward taught the women to lift weights and ran rowing-specific strength training sessions for them (as well as for various other groups of rowers over the years) twice a week in the evenings after his paying clients had left for the day (this was long before the days of ‘going to the gym after work’!).

“It was a very, very small gym,” Penny recalls but adds that, “It had more or less everything you needed,” which was a massive step forward.

Edward Sturges supervised Jill Ferguson doing squats. (Photo: Ann Sayer’s personal collection.)

Their first session was on a Thursday evening in late November 1963. Ann recorded in her training diary, “First gym session. Didn’t know what to expect – neither did Mr Sturges.” But they soon settled into a routine of Tuesday and Thursday weight training (with the UUs and Penny adding occasional tanking on Wednesdays and a run or circuit training on Mondays, Wednesdays or Fridays). Their last session was on 24 March, which shows that for all the recognition of the value of weight training, especially for women, it either wasn’t known or wasn’t acted up on that as women lose strength very quickly when they stop doing weights, this should have carried on for another three to four months.

From left: Ann Sayer on single bicep curls, Barbara Philipson on pull downs and Pauline Baillie Reynolds going for double bicep curls. (Photo: Ann Sayer’s personal collection.)

Still, the eight knew it was worth doing. Zona remembers, “I went up to it because it was in the evening and I was able to get up to it [from Caversham]. It was an awful way to go just for weight training. But we needed a lot more of that.” And whether from knowledge that this was what Penny had been doing all winter or just from observation of the effects, Freddie Page commented later in the Almanack that Penny, “Had gained a good deal of strength from hard winter work on water and land since last year.”

Ann Sayer spots for Daphne Lane on bench presses. (Photo: Ann Sayer’s personal collection.)

The ULWBC four also did weights because there were training facilities at ‘ULU’ the student union

Boats and blades

Both Penny and the UU eight had new boats for the 1964 Championships. After four seasons in a Frank Sims scull, Penny got a new Stampfli. Shortly before the Championships the eight decided to take up Quintin BC’s offer of their ‘schools’ boat ‘Tom Peters’ in preference to their own boat ‘Quarry’ (named as an elision of Quintin (their coach, Frank Harry’s club) and Harry). Although Quarry had served UU well, they were aware it was rather heavy and hadn’t used it at previous Championships either; in 1960 they’d used the Reading University new women’s eight, and in 1962 they’d borrowed ULWBC’s boat ‘Dick Franckeiss’.

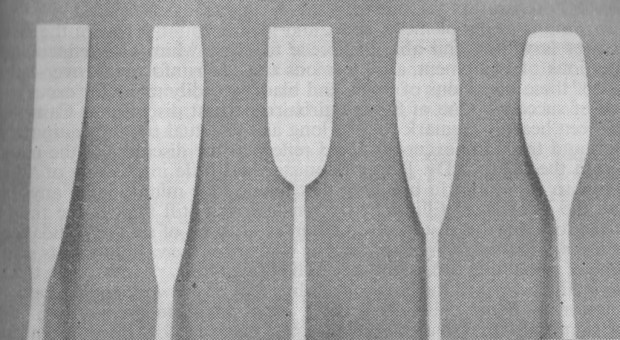

The eight’s big equipment innovation of 1964 was a new set of blades. Unlike Penny and the double, who had been using ‘macon’-shaped spoons which they had bought new with their boats (in 1960 in Penny’s case and in 1961 in the double’s), the eight were still using 1950s-style ‘pencil’ or ‘needle’ blades. The differences in shape can be seen clearly below.

Amusingly for those of us who remember ‘hatchets’ coming in around 1992 and referred to these as ‘big blades’ as their spoons were much larger than those of the the macons we’d been using in the 1970s and 1980s, some of the UU group nowadays refer to macons as ‘big blades’ which, to be fair, they were in comparison with the blades they had been using which they referred to informally as ‘toothpicks’ or ‘winklepickers’ (the height of fashion in ladies’ footwear at the time).

Spoon shape was actually a hot, hot topic throughout Europe around this time, so much so that a full three and a half pages were devoted to the subject in the 1964 edition of the Almanack in the form of an article by blade maker Peter Ayling which included this illustration:

Blade shapes from left: Conventional ‘straight’, Conventional ‘barrel’, Spade, Thames RC-type Spade, New design. (Photo: Aylings.)

The successful East Germans were some of the earliest experimenters with new blade types and ‘spade’ blades were first seen at Henley in 1960, having also been used in the Boat Race that year by the Oxford crew coached by Jumbo Edwards.

Being academic types, UU decided to carry out their own research on the subject before committing themselves to ordering new blades. Given that the whole area of blade shape and length was full of unknowns, with the most effective design for women being even more unknown, this was a wise move. On 14 March they tried Reading University Women’s RC’s Aylings spades on the Tideway for the first time, and liked them very much. Ann Sayer recorded in her training diary that, “For once we were able to work really hard. We haven’t been able to do so of late with our own set of small blades. Could really get onto the catch. Splendid blades in fast, following conditions. Not sure that would like such big bats in strong head wind on dead water. Unprecedented to rate 40 at this time of year.”

On 12 April they then tried Radley’s spades, with a more mixed response, “Bow pair liked them; rest of us not prepared to commit ourselves, but felt they were rather heavy inboard.”

After considering the measurements of the various options they decided on a compromise and created their own spoon design which was wider and shorter than the old ‘toothpicks’ but less so than the two sets of spades they’d tried. “We drew a few possible blade shapes. We didn’t know anything about hydraulics or mechanics,” Ann remembers. One was chosen (which was actually very similar to the Thames RC-style spades) and the order placed.

| Old UU blades | Reading spades Aylings | Radley Spades | New UU blades | |

| Length overall | 12’0″ | 11’11” | 12’0.5″ | 12’0″ |

| Length inboard | 3’8″ | 3’8″ | 3’8.5″ | 3’8″ |

| Width at tip | 5.25” | 7” | 7.25″ | 6” |

| Width 10” from tip (widest point) |

5.75” | 8” | 8.25″ | 7” |

| Length of spoon | 32.75” | 24.5” | 20.75″ | 26.5” |

| Area | 150 sq inches | 161 sq inches (7% larger) | 145.3 sq inches (3% smaller) | 154.6 sq inches (3% larger) |

On 20 June they had their first outing with the new ‘Sayer/Ayling’ shape. Ann noted in her diary, “Lost some sleep last night lest they turned out to be a failure. Relief that we all liked them – even Barbara (who had said they were ‘too small’).”

The UU eight training with their new blades at Weybridge just before the Championships in 1964. (Photo: Ann Sayer’s personal collection.)

Equipped with their new oars, they embarked on a three-day mini training camp in Weybridge where they tested another equipment innovation according to Anne’s diary:

Wednesday, 22 July: Tried out new Bakers aluminium gates on all riggers except mine because screw thread worn. But we will try new gates again tomorrow morning.

Thursday, 23 July: Put back old gates after one unsuccessful outing with aluminium gates.

The UU accounts show that they received an invoice in mid-August for £11.4.0 from Matt Wood for “swivels etc.” which presumably includes these unappreciated aluminium swivels. Frank Harry paid it himself.

Ann also noted, “Sir [the group’s name for Freddie Page] again trying to get uniformity of swing by constant reference to chalked marks on side of boat,” and that at the end of the camp he told them that, “We are the most hard-working crew and most technically proficient ever sent to Championships – he did not say to us that we were faster!”

The shortness of their training camp compared to previous years reflected the fact that as six of the crew were teachers or lecturers, they simply had very little time between the ends of their terms and the start of the Championships.

Frank Harry and the UU eight eating ice lollies during their Weybridge training campette. (Photo: Margaret McKendrick’s personal collection.)

The UL four also had a training camp in Weybridge where UL coach Dick Franckeiss had a hut in which they stayed. “We cooked on a primus stove and slept on mattresses on the floor which was terribly hard and I ended up with bruises on my hips,” remembers Christine Davies.

Beryl Fox (left), unidentified cat, unidentified small girl, and Christine Davies at their training camp in Weybridge. Note the Championships poster decorating the door. (Photo: Christine Davies’ personal collection.)

Christine recalls that Freddie Page continued to look after them, “[He] was quite a support, he actually invited us to [his home in Barnes] – it’s a house there with a turret overlooking the river and everything… but he invited us to a do there which was absolutely wonderful. Completely out of this world – people playing croquet by candle light! And that was probably the week before we went over to the Bosbaan.”

Other preparations – on and off the water

A few days after their new blades arrived the eight had raced at the Koninlijke Regatta on the Bosbaan, with Lesley Bourne from Civil Service Ladies HQ RC coxing instead of Margaret McKendrick. It didn’t go well although it was a sort of learning experience, as Ann wrote in her diary, “Disastrous weekend! We rowed chaotically and in rather panic-stricken manner. We have, in fact, become unused to racing beside other crews. In Britain, even if we row badly, we generally lose our opponents fairly quickly and then we settle down. An expensive way to find out that we must tidy ourselves up mentally and psychologically.”

Ann also noted that, during the summer, “Several interesting cine films were eventually taken (thanks to Penny Chuter) and the eight was grateful to discover that, rowing-wise, it looked a good deal tidier than it felt.”

The crew’s final ‘equipment’ innovation for 1964 was in the shorts department. Having liked the ‘gym knickers’-style continental women’s rowing shorts they’d bought in Berlin in 1962, which they couldn’t wear when racing as GB because they were black and GB kit at the time required white shorts, Zona Howard decided to knit some. Yes, knit. Albeit with a knitting machine. “It was just a case of going backwards and forwards on it and it was fairly easy to do,” she says, downplaying the amount of work this must have involved. “Of course they took a long time to dry because they were wool. But at any rate they were more comfortable to wear.” They had blue and red ribbons sewed down the sides in GB colours. Margaret McKendrick still has hers, although it’s some years since she last wore them.

A good luck card from the UUs to Penny, with some in-joke spelling.

Funding

Following the Women’s Amateur Rowing Association’s merger with the Amateur Rowing Association (previously men-only) at the beginning of the previous year, the coffers of the ARA’s International Fund were now available to cover the GB women’s team’s expenses for the Championships. Ann Sayer wrote in her training diary, “This year for the first time at the championships, a UU eight was able to benefit financially from the ARA/WARA merger… on this occasion the ARA kindly paid for our boat transport and accommodation in Amsterdam.” This amounted to £191.3.8.

Even the ARA’s finances were decidedly modest – there was no question of funding athletes, coaches or equipment, of course – but they were a step up from the Women’s ARA’s budget which was funded from coffee mornings, quizzes and the like, and the ARA made it possible to start sending crews to Championships again without ‘ability to self-pay’ being a necessary selection criterion.

At the Championships

All three crews traveled to the Championships in their own cars although in Penny’s case, she borrowed Jill Ferguson’s car because of a mildly complicated itinerary the details of which are not pertinent. However, when she came to loading her single on the departure day it rapidly became clear that her non-adjustable roof rack was too wide for Jill’s car. The only solution was to wind the front windows down slightly and clip it over the front doors, which worked but did mean that the doors couldn’t then be opened. Penny therefore had to climb in and out of the window every time she got in or out of the car, which, she recalls, “Amused many onlookers at the ferry terminals and on the ferry, and especially in the middle of Belgium where she stopped for petrol when an old petrol pump attendant couldn’t believe his eyes.”

Frances Bigg took the roles of Team Manager and coach of the four, and Frank Harry was able to accompany the eight for the first time since 1960 (as the intervening Championships had all been behind the Iron Curtain whence his wartime work for the Home Office precluded him from going). What this meant in practice on their first day in the Netherlands was that he went to the beach with them.

UU at the beach at Nordwijk with a slightly bored-looking Frank Harry. (Photo: Ann Sayer’s personal collection.)

When they did get round to rowing, everything seemed to be falling into place nicely, as Ann Sayer recorded in her training diary:

Monday, 27 July: Bosbaan. So pleasant to be on Dutch water in an English boat! [On the various occasions when they’d come over to compete at Dutch regattas before they’d always borrowed a boat.]

Wednesday, 29 July: Course in 3:26 – one of our best rows ever. Penny, who is really sculling well, did course in 3:48. We’re not in the same class!! But we were pleased.

Kathleen ‘Kay’ [Henderson, the reserve] – now nicknamed Tiger after her tiger-print bikini and digging habits on the beach [see photo above] – swapped in for Marg at three for a quick spin. [The UU group continue to call Kathleen ‘Tiger’ now.]

A development at the Bosbaan course since the Women’s European Rowing Championships had last been there in 1954 was that the lanes were now buoyed in the way we’re used to nowadays instead of whacking great big ones that could knock a sculler in if they clipped one (as had happened in Moscow the previous year), and no more having to wait till you go to one of the overhead lane markers to find out if you were in the right place. A step forwards in course arrangements.

Margaret McKendrick’s competitor’s badge.

Results

Penny Chuter (fourth out of seven)

On the first day, Penny was drawn against Alena Postlova of Czechoslovakia, who was the only sculler she had expected to beat her the previous year (although this had all come unstuck in rough conditions in the final which led to Postlova falling in and Penny hitting a buoy whilst the less-favoured Russian had a sheltered lane), and a new Dutch sculler called Meike De Vlas.

Only one sculler would progress straight through to the final, and although Postlova won by nearly two seconds after leading all the way, “Penny Chuter felt she could have beaten her if she had known she was so close,” according to a report in the October/November issue of Rowing magazine. De Vlas was nearly seven seconds further back, apparently playing a tactical game and not overdoing it.

The repechage proved to be almost a formality; with four scullers to qualify from five and the Belgian winding down very early on in the race. An unidentified newspaper reported that, “Miss Chuter, striking 28, strolled through today’s repechage,” coming second, which is exactly how you want to do it, of course, although Rowing suggested that, “Her victory would have sounded a warning note for the final.”

In the six-boat final, Penny finished fourth for the fourth time in five European Championships. Desmond Hill described her race in detail in The Telegraph:

Miss Chuter overhauled after grand start

Penny Chuter failed gallantly in the sculls, a disappointment which was all the more galling as she had raised our hopes in the early stages.

She started with 42 strokes in the minute and was at once in the lead, but, after 250m, Miss Konstantinova, the Russian, had inched past.

Miss Postlova (Czechoslovakia) had joined Miss Chuter at half way but a great effort took Miss Chuter away once more. She was just over a length behind the Russian and apparently gaining.

Suddenly, the unconsidered Dutch girl, Miss De Vlas, materialised in the shelter of Lane 6 to pass both Czechoslovakia and Britain [and snatch the silver medal]. Miss Konstantinova had less than a second to spare at the end.

Rowing‘s report tells a similar story; “Penny Chuter jumped the gun and was recalled. She then set off tremendously fast with a full 42 and was ahead by 250m. Konstantinova (USSR) and Postlova (CZE) had passed her at half way but she was back in second place and apparently gaining at 750m. De Vlas raced up late in the sheltered Lane 6 and many thought she had won. Less than five seconds covered the first four scullers.”

Penny in fourth place during the single sculls final. (Photo: Frances Bigg’s personal collection.)

Weather conditions

At this point it’s worth picking up on both these reporters’ brief mentions of ‘shelter’; Freddie Page’s report in the Almanack is clearer about the weather, saying that, “A strong following wind blew throughout the regatta,” and Penny and members of both the eight and the four all remember rough water caused by a tailwind at the Championships. Penny recalls it being, “Extremely rough and one side of the course was OK and the other side was not so good”. Similarly, Ann Sayer wrote in her diary at the time that, “Several of us had no nerves at all by time race arrived having seen three previous races in afternoon where high lane numbers patently had advantage over low ones. It made getting nervous seem a little pointless, when elements are not evenly distributed. Jill and I even shed a quiet tear when watching earlier racing.” Margaret McKendrick says, “I can remember it being so rough with a following wind. As we approached the landing stage, I was screaming ‘Somebody stop us because we can’t’ – you know, all the blades in the water wouldn’t stop us.” Zona agrees; “Oh, it was dreadful. The long rollers that make it so difficult.” And Christine Davies from the UL four also remembers it being, “Terribly rough. Terribly rough. We were going faster than we’d ever gone before but trying to keep control in these great big waves it really wasn’t nice.”

Furthermore the results in the Almanack indicate that there was a tailwind during Penny’s final of 5 m/s, which is the speed at which FISA would expect to have to start reviewing fairness and rowability on international courses nowadays.

In an Almanack report about men’s Championships that year, Freddie Page wrote with typical British stoicism, “Although it can not be truly said that stations on the Bosbaan are always equal, for when the wind is in certain directions it plays awkward tricks; but oarsmen know that this is the luck of the draw on any existing course and this at Amsterdam comes as near as possible to perfection (short of an entirely covered-in basin!).”

Penny is certainly pragmatic now about the fact she hadn’t rigged for even slightly rough conditions:

Because I didn’t have a coach to guide me, I had to make my own decisions. The closer closer athletes get to events, the more conservative they become and the less they are inclined to change anything. If I had known then what I know now I would have whacked up my riggers in those conditions quite considerably. You don’t have to change your rigger height very much these days because, particularly in sculling, we scull with higher riggers than in my day so it’s not as critical if you’ve got choppy water or a dead flat calm. But then they were so low that the slightest popple on the water you needed to lift them up. I just didn’t make that decision, whereas if I’d had a coach, they would have said, ‘Go on, riggers up,’ and I would have just got on with it. So I didn’t scull well in that final because my riggers were just too low for the rough conditions. This isn’t an excuse, it’s just a fact.

Back to Penny’s results

After coming fourth in her rookie year in 1960, then fourth again in Prague in 1961, second in 1962 in rough conditions, fourth in terrible conditions in Moscow in 1963 and then fourth again in Amsterdam in 1964 in more dreadful conditions, Penny says, “I thought ‘I’ve had three years running and I’m just not going to do this any more,'” although she admits, “But I had more or less decided [that this would be her last year] anyway because I’d already applied to go to PE College.”

Freddie Page said in the Almanack that, “Penny was not quite at her best and seemed to have lost some of her zest although her technique was judged to have improved,” which certainly doesn’t come over in Penny’s own memories of that year, and may have been written with the intention of suggesting that he believed her to be faster than the result indicated.

Eight (sixth out of six)

After ten straight years of winning the eight, the Russians were beaten by Germany. Romania were third, Holland fourth, Czechoslovakia fifth and GB sixth, almost five seconds down on the Czechs and over 20 seconds down on the Russians.

The start of the eights’ final. GB are in Lane 3 in white (Lane 6 is nearest the camera). Photo  GLW Oppenheim Amsterdam.

GLW Oppenheim Amsterdam.

Ann Sayer recorded her memories of the eight’s straight final in her training diary:

We set off at 42. It felt quite comfortable to me. Rest of course at 38.

Czechs should have beaten Dutch. If we had rowed an absolute blinder I think we could have beaten Czechs (in fair conditions).

The crew had been considerably better than previous UU crews until May, but it did not maintain its improvement until the big day. Was our disappointing performance due to the fact that the early date of the Championships gave us no time to recover from the usual spell of exhaustion at the end of the summer term? Or was it old age? We’ll never know.

A report in Rowing magazine added that, “United Universities rowed 42 for the first minute but were always trailing and might perhaps have done better with smaller blades.” As Rowing at the time was owned by Aylings the oar-makers, the comment about blade-size could be an indication that Aylings didn’t agree with the input UU had had to their blade design.

The effect of the strong tailwind can be seen if you look closely in the video below which shows all of the finals.

Coxed four (unplaced out of eight)

The UL four came third in their heat of four, beating Denmark by nearly six seconds, a feat which they repeated in the repechage, with the difference nearly seven seconds that time. They were 8.48 seconds off qualifying for the final, though.

The UL four going out to train (judging from the lack of flags or spectators about) on the Bosbaan in windy conditions. Why their cox is wearing a skirt is a mystery. (Photo: Ann Sayer’s personal collection.)

Or, as an unidentified newspaper clip put it, “The London University Four were eliminated in today’s repechage finishing fifth of six. They were above 40 at the quarter distance,” but as Rowing then explained, “The British four could not cope with the rough water and caught two crabs, the second of which destroyed all hope of their catching Hungary.”

The GB four (on the left) finishes behind Hungary but ahead of Denmark in their first round heat. (Photo: Frances Bigg’s personal collection.)

The wonderful video below of the team relaxing, training and racing was taken on Penny Chuter’s 8mm cine camera by her, by other members of the United Universities eight, and by Peter van Niftrik (in particular the sections taken on his bike while cycling alongside Penny doing practice starts) and his wife (who appears early in the film). Peter was President of the Koninkljke Regatta at that time, a coach at De Hoop rowing club in Amsterdam, and had also been involved in designing the Bosbaan course, and Penny had got to know the van Niftriks from competing at other events in the Netherlands earlier in her career.

This video is repreduced here with Penny’s kind permission.

Roundup and observations

“The results fell short of our expectations,” was Freddie Page’s concise summary of the team’s performance in the Almanack. Which is complimentary, in a way.

He added, “What a pity it is that we do not develop the attractive and exciting art of quadruple-sculling of which the Continental girls are such graceful and skilled exponents. There is probably no more suitable form of boatracing for women than this and double sculling, and how work in these boats would improve the rowing in eights and fours!” [Which indicates how eights and fours were considered THE important boats at the time, of course.]

Also writing in the Almanack, Grace Wilkinson, Vice-Chair of the Women’s Amateur Rowing Committee, observed that, “The standard at Amsterdam was almost terrifyingly high, and no oarswoman in this country except Penny Chuter ranks anywhere near the best of the European crews. This is due, at least in part, to our small number and lack of outside help, but it occasionally gives a slightly unrealistic appearance to domestic regatta results.” She also noted that, levels of entries at domestic regattas “were below the level which existed some years ago.”

Commemorative medallions were given to all members of the team. (Source: Frances Bigg’s personal collection.)

Around the Championships

This was the fifth Championships that the UU group had attended, in varying numbers, so they had got to know some of the other countries’ regulars. Margaret McKendrick remembers, “We all got on very well with the Russians. They had a little doctor with them, a female doctor. She caught me by the arm on one occasion, because I hadn’t got any shoes on. Of course, she spoke in Russian and I didn’t understand what she said. And I said to Marrian [Yates, who spoke Russian], ‘What did she say?’ And Marrian laughed and said, ‘She said, “Go and put your shoes on, you’re not a peasant girl!”’ And then of course I stubbed my toe and was limping the next time, I didn’t need to translate what she said – ‘Serves you right!'” Margaret adds, “Because they knew we never had anybody with us they always said, ‘We’ve got boatbuilders, we’ve got doctors if you need them.'”

She also remembers, “The East German double scullers came [to us] one day and said, ‘We know you’ve got your cars. We’ve never seen the sea. Could we go and look at the sea?’ So we packed them into the cars and took them off to one of those nice Dutch beaches and spent the afternoon building sandcastles. And of course East Germany was completely enclosed because they couldn’t get to the Baltic coast. It was all cut off. And so they had never seen the sea.”

Team Manager Frances Bigg (Photo: Frances Bigg’s personal collection.)

Christine Davies and the UL four were thoroughly enjoying themselves, which may have ruffled some UU feathers. “We thought it was a wonderful experience being there,” she remembers. “The hotel was on one side of Amsterdam. They’d have coaches taking us across and everyone used to sing. There’d be the Russian team there singing the Volga boat song or whatever it is and it was just a wonderful, wonderful atmosphere. Frances Bigg was team manager [and] had a quiet word with us because the UUs were getting upset because we seemed to be enjoying ourselves so much and they seemed to think we weren’t taking it seriously enough.”

Speaking from the UU point of view, Margaret McKendrick admits that having the UL four at the Championships changed the dynamics of the team, which was no longer just the close-knit ‘UU plus Penny’ group as it had been since 1961. “We had a reputation for never stopping talking but never listening to what was said!” she laughs. They all certainly enjoyed each other’s company; Daphne Lane remembers that, “During the week following the championship I chartered a sailing boat in Friesland [in north east Holland]. Penny Chuter joined me, along with a couple of other folk.”

The UU eight weren’t the only members of their GB team who liked sunbathing but at least these members of the UL four kept their hats on. This photo appeared in a Dutch newspaper captoned with the inevitable pun, “Warming up at the Bosbaan”. From left: Margaret Gladden, Beryl Fox, Christine Davies, Bridget Pendered. (Photo: Christine Davies’ personal collection.)

The men had started arriving at the Bosbaan by the time the women were racing, and there must have been a certain amount of mixing as Christine Davies remembers swapping her GB cap with the cox of the Russian men’s eight which had taken Henley by storm that year, not only winning the Grand but setting new course records in all three of their races.

Her crew-mate Margaret Gladden bought some traditional wooden Dutch clogs, and was pictured wearing them in The Times the next year along with the comment, “Just the thing for muddy towpaths!”

Margaret Gladden in her Dutch clogs, accessorised by a rudder.

Conclusion

By the end of the 1964 Championships, although the merger with the ARA had brought new funding into GB women’s international rowing, Penny Chuter had stopped and the UU group which had provided most of the team since 1960 had now competed at five Championships as well and clearly weren’t going to be around for much longer. If anything, women’s rowing at grass roots level was declining; a few months later Pauline Baillie Reynolds, Ann Sayer, Marg Chinn and Barbara Philipson, coxed by Jean Good, won the Women’s ARC Fours Head by 17 seconds despite not rowing at all well (although admittedly they were in a shell boat and all the other crews were in clinkers – itself a damning indictment of the state of equipment in British women’s clubs). As Ann noted in her training diary, it was an “appalling commentary on women’s rowing in this country when we, rowing as badly as we were, can win by that much – or even win at all!”

The future was not looking bright, and there wasn’t even a visible way forward.

GB men’s rowing hadn’t been exactly flourishing either although the number of men rowing at clubs was very much larger. However they had at least started to try and enter a new era; the Almanack reported that, “Our most important current development [in 1964] is the formation of a national team with a view to increasing the standard of our rowing… This scheme was put in hand at the wish of ARA clubs who have backed it by encouraging some of their more promising oarsmen to offer themselves for the national squad.”

← Back to 1963 | On to 1965 →

© 2017 Helena Smalman-Smith.