The 1985 World Rowing Championships took place at Hazewinkel in Belgium from 26 August to 1 September. They were the first World Championships to include events for women’s lightweights, and also the first at which women raced over 2,000m, the same distance as the men, rather than 1,000m as they had since FISA first sanctioned international women’s racing in 1951.

58 openweight and 32 lightweight women’s crews competed from 24 countries. This was the second lowest number of openweight crews to have competed at a World Championships since women’s events were first included in 1974, and the only time that there had been fewer was when they’d been in New Zealand which had inevitably limited ‘development’ entries from European crews on the grounds of cost. Looking at it another way though, the total number of women’s crews racing was actually the highest ever.

A third significant change to the racing programme at these Championships was that the women’s quads were now coxless.

Management and funding

The situation in 1985 was far from ideal in terms of squad management. Although Rosie Mayglothling was now in her second year as National Coach for Women’s Rowing, which included being GB squad co-ordinator, she also had considerable duties in developing rowing domestically.

As in 1984, there was a joint Selection Board for the 1985 season, formed from selectors associated with men’s, women’s junior men’s and junior women’s rowing. Women’s rowing was represented by former internationals Chris Aistrop and Christine Davies, both of whom had been Selectors before.

Funding

British international rowing had never been well-funded, but the budget for 1985 was much, much lower than before as the Amateur Rowing Association’s agreements with its two main sponsors (National Westminster Bank for the men and British Home Stores for the women) had ended after the 1984 Olympics. As a result, the plan for the year involved non-residential assessment weekends, and the summer racing programme was only expected to include a minimum of overseas events.

Objectives and plans

Rosie issued a policy for the women’s international rowing scheme in October 1984 which was explicit about being part of a longer-term plan and not only focused on that year. The objectives for 1985 were:

- To produce the strongest possible team for the 1985 World Championships.

- To produce the largest team possible of the required standard.

- To initiate a programme oriented towards identifying and developing younger talent, aiming for the 1988 Olympic Games.

The document also stated that, “To be selected, a crew should be the fastest in its category in the country. However, if there is no outstanding crew seeking selection in a particular event, selection may be made of a crew with younger members showing promise for future teams in preference to an older crew… even though the older crew may be faster.”

In contrast with previous years, squad land training in London was to take place at a number of venues, and water work was to be done in small boats (coxless not coxed fours, leaving potential squad coxes nothing to do initially) in locations to be decided once squad registrations had been received. These sessions were run by Mike Genchi, Noel Casey, Phil Tinsley, Michael Yetman and Doug Parnham, the National Coach for Junior Rowing.

Three assessments were planned for late November/early December in York, Walton on Thames and Chester, mid- to late January at the Docks or Thorpe Park near Heathrow, and April.

There would also be ergometer tests – using Concept 2 machines for the first time – in January (8 miles [! –Ed.]), March (6 miles) and April (4 miles) with pull up and bench pull tests and two mile runs on the same days as these too.

How all of this panned out was that for financial, practical, and ‘it just happened like that’ reasons, all seven of the boats which represented GB that year trained – and raced, even – in different places and were largely unaware of each other. Their identity as a national squad was decidedly nominal rather than practical.

The lightweights

The new women’s lightweight programme in the World Championships comprised three boat classes (although these weren’t confirmed until the international rowing federation, FISA, voted through the changes at its Extraordinary Congress in January 1985): coxless fours, double sculls and single sculls. Britain entered all three.

The coxless four

The coxless four was run as a formal squad by volunteer coach Mike Genchi of Lea RC. Mike had coached the lightweight women’s eight which had taken part in the trial women’s events at the FISA Championships for Lightweights in Montreal in 1984, which he’d been invited to do, as he remembers it, by Rosie Mayglothling or Penny Chuter, the Director of Coaching, who both knew him through his wife Jean, a GB openweight international.

The creation of the new lightweight squad and the introduction of lightweight events at the National Championships in 1984 led to selection being considerably more competitive in 1985 than it had been for the test events in 1984. In addition, of course, there were fewer seats available as there wasn’t an eight, and also the highly experienced openweight internationals Beryl Crockford and Lin Clark had dieted down and were the ‘no brainer’ choice for the double.

One of the eventual lightweight four, Melanie Holmes, had represented GB at openweight in 1982 and had been a GB junior before that, and Melanie and Sally-Ann Petrie had both been in the lightweight eight in 1984, but the other two crew members were new to international competition.

With the lightweight women’s squad being a new development, and all women’s openweight racing in four-person boats (fours or quads) having been coxed anyway, the Amateur Rowing Association (ARA) didn’t have a boat for the coxless four. As there was no budget either, Mike Genchi persuaded the London Docklands Corporation to pay for half of the cost of the boat, and funded the other half himself (money which he only eventually got back from the ARA, after considerable negotiation).

Although GB had had a men’s lightweight squad since 1974 when FISA first introduced the category, none of their experience in dieting to row lightweight was shared with the women. “We were competing against the Canadians, Americans and Australians who all had big domestic lightweight systems, but everything was such a new experience for us and we had no real information about weight loss,” Mike remembers.

The double scull

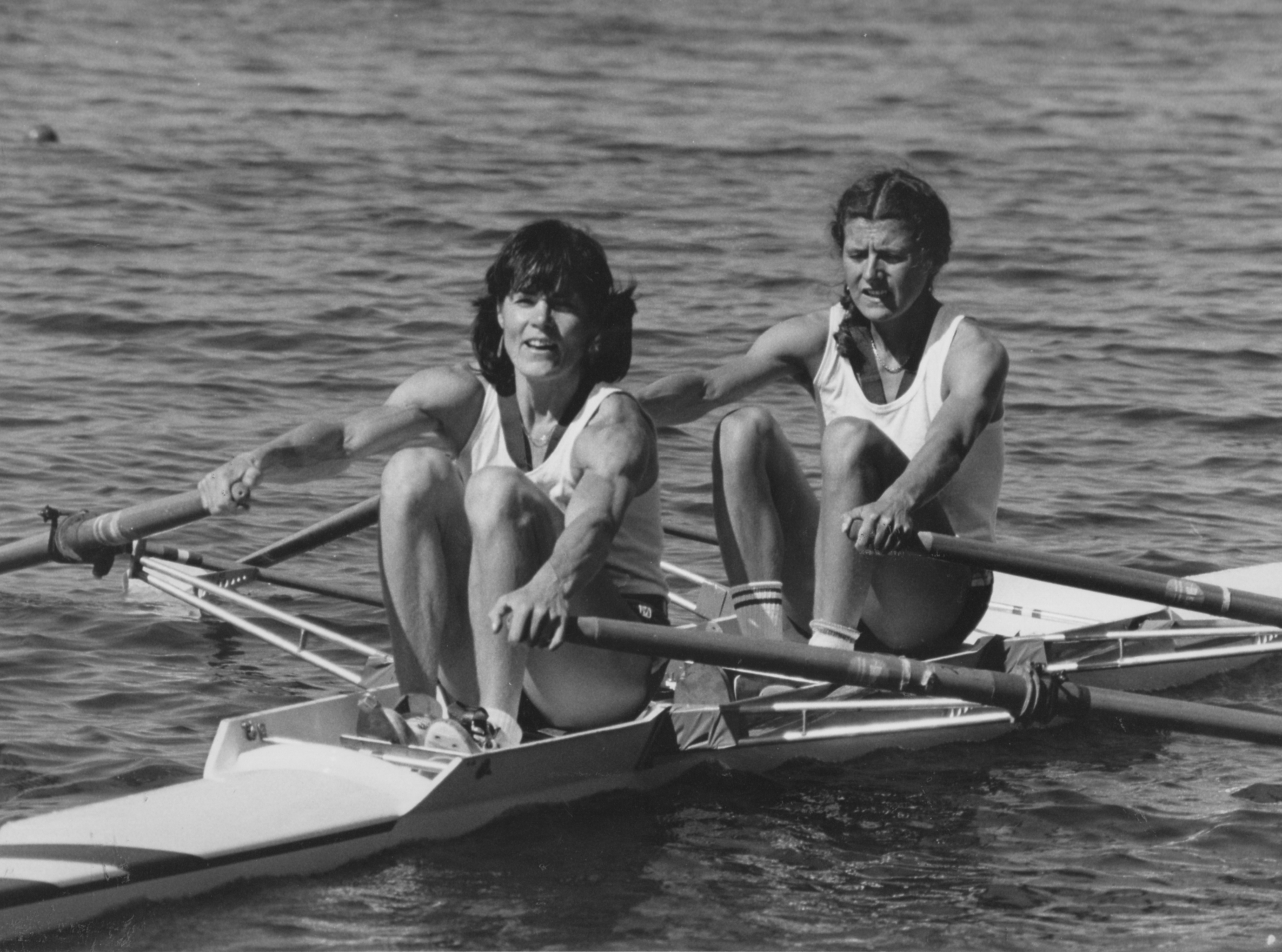

The highly experienced double of Beryl Crockford (formerly Mitchell, who changed her name during the year after marrying Duncan Crockford, then the Captain of Leander Club) and Lin Clark was a privately-organised, coached and funded crew. Both of them were 35 by the time of the Championships.

For the previous six years, Beryl had competed as an openweight single sculler, during which time she achieved a superb silver medal in 1981, but otherwise had not got the wins she sought. After seeing her long-time training partner and good friend Lin Clark do well at lightweight in the single scull at the test event for women at the FISA Championships for Lightweights in 1984, Beryl asked Lin if she would do a double with her.

In a piece she wrote in July 1985, Beryl explained the opportunity that the change from 1k to 2k racing and the creation of lightweight events provided, saying, “Up till now I have had to race against East Europeans and others who have been much taller and heavier. 1,000m takes three and a half to four minutes in a single scull depending on the conditions, and the emphasis is very much on explosive strength which is developed… with heavy weight lifting as well as circuit training, running and water work. 2,000m is much more an endurance race which actually suits women better and lightweights in particular. So, when the new lightweight category was announced I decided to take up the challenge which for me meant losing 1.5 stone.”

Having represented Thames Tradesmen’s RC for a long time, for the 1985 season both raced for the Hammersmith-based Sons of the Thames RC, which Lin had joined the previous year because the club offered her racking for her sculling boat.

For the first part of the season they used a Janousek boat but this was too heavy for them and for the World Championships rowed in a wooden Stampfli which Graham Wyatt kindly bought for them.

Coaching

The double was coached by Mark Hayter and by Lin’s husband Jim Clark. Mark had coached Beryl as a single sculler from 1980 to 1982, a period which included, of course, her historic openweight silver medal success at the World Championships in 1981. Jim had then coached Beryl in 1983 and 1984. From January 1985 he was living in Italy where he was coaching the Italian men’s National Squad, which turned out to be fortunate for Lin and Beryl as he was able to get them to join the Italians on an altitude training camp in St Moritz later in the year. Beryl was later quoted in the Observer as saying that they wouldn’t have won without this opportunity.

The camp was directed by Thor Nielsen, one of the world’s most influential rowing coaches at the time, whom Jim describes as being, “Both generous and thoughtful in helping Lin and Beryl fulfill their potential,” and adds that, “The double was so disjointed when they arrived in St Moritz, but the consensus that Thor and I had come to was that they could be a gold medal crew, and by the time they got to the World Championships they raced well.”

Mark Hayter recalls, “Lin and Beryl were both very strong characters, and although they were very close friends, their relationship was quite stormy at times that year. Coaching them was quite psychologically draining, but it all came good on the line.”

Becoming lightweight

Lin had already got down to lightweight and started racing over 2,000m in 1984, having understood as soon as these changes were introduced to women’s racing that they offered her a much greater chance of winning a medal. For Beryl, this was all new, although she realised the both provided a tremendous opportunity. In a piece she wrote in July 1985, Beryl explained, “Up till now I have had to race against East Europeans and others who have been much taller and heavier. 1,000m takes three and a half to four minutes in a single scull depending on the conditions, and the emphasis is very much on explosive strength… 2,000m is much more an endurance race which actually suits women better and lightweights in particular. So, when the new lightweight category was announced I decided to take up the challenge which for me meant losing 1.5 stone…. To achieve this goal I had to change my training pattern and my eating habits. Changing the training was easy, a shift from heavy weights to very light, high rep weights or no weights at all, a massive increase in running mileage (the most effective exercise for weight loss in my experience)… the change in training enabled me to lose muscle bulk while training for endurance.”

Sponsorship

With no funding for women’s lightweight rowing from the ARA, Beryl and Lin, as they had on several occasions in the past, just coolly got on with finding their own financial support and secured a sponsorship deal with the bra-maker Playtex. In her July 1985 piece Beryl described how the brand was the ‘perfect fit’ for supporting [yes, OK, pun intended – Ed.] two lightweight rowers:

As many dieters will know to their cost, once they have lost the weight they find that they have lost other things too… half their wardrobe that doesn’t fit anymore and even more disconcerting is the loss of bust. I never had a large bust but a good deal of what I did have has now gone and the problem of a small bust is finding a bra that fits and can give enough support which is especially important when training. I’m glad to say that I have managed to find such a bra and at the same time a generous sponsor to help cover our considerable equipment and training costs. The sponsors and the makers of the bra are Playtex who have recently launched a new bra called ‘Thank goodness it fits’ which is designed specifically for the small busted woman.

When reporting the sponsorship deal, Rowing magazine took the obvious opportunity of commenting that, with women’s racing now over the longer, 2k distance, “Thank goodness they’re fit.”

Fiat International in Turin paid for Lin’s attendance at the Easter training camp and these sponsorships, along with the Graham Wyatt’s purchase of their boat and the support they received from Sons of the Thames RC in terms of racking and facilities, all joined together to enable their success. As Lin put it, “It was a case of rowers helping rowers, regardless of gender, country or club.”

The single scull

A set of trials for the lightweight single sculls were held at the docks in April 1985, and there may have been other occasions too. In the end, Carol-Ann Wood, known as Carrie, from Furnivall Sculling Club, who had been the official GB entry at the test event for lightweight women held at the FISA Championships for Lightweights the previous year, got the seat again after she won lightweight singles at the National Championships by a substantial margin.

Carol-Ann didn’t really have a dedicated coach for most of the year, although she was part of a group of single scullers who were coached on the water by Bill Barry of Tideway Scullers which shared a boathouse with Furnivall at the time. After she’d been selected, Rosie Mayglothling arranged for Molesey BC oarsman Jon Tompkins to look after her for the remaining six weeks or so up to the World Championships. “Working with Jon was great because it was the first time anyone had ever talked to me about race plans,” she remembers.

The Eastern bloc and lightweight rowing

By the time women’s international lightweight events were introduced in 1985, men had already been competing at lightweight for eleven years in the FISA Championships for Lightweights. During this time, there had rarely, if ever, been entries in these from the Eastern bloc countries which dominated openweight men’s and particularly women’s rowing.

It’s widely accepted that most of the Eastern bloc countries were doping at that time, with athletes taking anabolic steroids both to increase their muscle development and improve recovery times to enable higher training loads. However the drug-taking wasn’t the only reason for their success; the facts that their crews were able to train more or less full time on state-funded programmes, and that these programmes selected individuals to take part in them based on physical attributes such as height were at least as significant.

Lightweight rowing wasn’t a sphere where most of these advantages could be taken, of course, and it’s not unreasonable to assume that this is why the Eastern bloc generally didn’t participate. After all, the state funding was a form of propaganda, both domestically and internationally, to demonstrate the dominance of the political regime, and there was no point in spending money on an area of racing where the required success would be harder to achieve.

For Britain and other Western crews, the absolutely critical importance of this is that not only were our lightweight crews competing against athletes their own size but against nations with much more comparable approaches to sport as an amateur activity, although there were a few exceptions such as the 1985 Romanian silver medallist in women’s lightweight single sculls.

The openweights

In contrast with the rightly optimistic, determined and competitive atmosphere in the various parts of the lightweight squad, GB women’s openweight rowing in 1985 has been described by several of those involved as “disappointing”. Most of the 1984 team had stopped rowing internationally after the Los Angeles Olympics, at least for the time being.

Eight

A development eight was eventually formed that was coached initially by Phil Tinsley, and later by Steve Gunn, who was one of the main architects of Hampton School’s considerable success at that time.

Tessa Millar was the only member of the group with senior international experience, having represented GB in the coxed four in 1983 and 1984. All of the others were new to senior international rowing although another four had been junior internationals. “I was really happy to be in that eight so long as it was making progress,” Tessa says. “But it needed considerable expertise to develop it, or it was just going to be a wasted year.”

The eight rowed in a ‘front loader’ boat (with the cox in the bows), a configuration which was quite fashionable with continental crews at the time, but which stroke Judith Burne remembers being “really frustrating” because she wasn’t able to communicate with the cox. It was a particularly inappropriate craft for such an inexperienced crew.

Coxed four

During the Easter holidays, Rosie Mayglothling’s husband Nigel, who was chief Coach of Oxford University Women’s BC, took some of his squad to the GB women’s main training base at the ARA in Hammersmith once their March Boat Race was over, and encouraged them to consider this as their next step.

“He was instrumental in effectively introducing us into the women’s GB squad,” says Tish Reid, who had rowed in Osiris, the Oxford reserve boat. “So that Easter break I was messing around, having my first introduction to squad rowing, jumping in and out of boats and really being a very young, naive novice compared with what all these internationals were used to doing.”

Following this, Noel Casey, who had been coaching GB women’s crews since 1981 as well as at Thames RC, pulled together a four comprising Ann Callaway and Sarah Hunter-Jones from the 1984 Olympic eight (Sarah had also represented GB in 1981 and 1983), as well as two of the Oxford group, Tish Reid and Ali Bonner. They were coxed by Lesley Clare who had been in Isis, the Oxford men’s reserve boat.

The training logistics for this crew were considerable, not only because three of them lived in Oxford during term time and Tish Reid continued to race with Oxford through to Nottingham City regatta in mid-May and the British Universities championships, but also because Ann was working shifts as a junior hospital doctor. This meant that they largely trained on their own and rarely came across the rest of the openweight squad. They spent quite a lot of their time on the still water, multi-lane environment of the George V Dock (a small one on the other side of City Airport from the Albert Dock where the London Regatta Centre is now). “It was very much pre-development in those days,” Tish says, adding, “The highlight was having breakfast in between outings at George’s Diner, where Noel used to have a huge steak while we had toast.”

Coxless pair

Like the lightweight double, the openweight coxless pair was a privately-organised crew which gained selection by proving itself to be the fastest crew in its category at trials held at the London Docklands.

The two crew members, Belinda Holmes and Fiona (who became known as Flo) Johnston, were very different on paper but enjoyed rowing together and did so effectively. Belinda was a highly experienced international, having been a GB junior in 1979 and 1980, and then in the senior team in 1981, 1982 and at the 1984 Olympics. Flo was a schoolgirl.

After the Los Angeles Olympic Games, with little happening in terms of a formal women’s squad, Belinda was training in a single scull out of Mike Spracklen’s house just below Marlow lock on the Longridge stretch. This is regarded by many as one of the best places on the Thames to row, as it’s long and mostly deserted because it doesn’t run through a town. Spracklen had coached the men’s coxed four which won gold in LA, and was now coaching two of that crew – Steve Redgrave and Martin Cross – along with Adam Clift. Redgrave was single sculling and the other two were in a pair. At the time Belinda lived in Marlow with Steve, so it was convenient for her to train with the three men, although in other ways not ideal.

Flo, meanwhile, had learned to row at Marlow RC, but had taken to sculling as her December birthday meant she was ineligible to row as a GB junior in her last year at school, and her junior four was disbanded. After a couple of impressive performances in autumn sculling heads, Belinda asked her if she’d be interested in trying a pair.

“Mike would make us do these long, long pieces all the way from Cookham Bridge back to his house against the stream,” Flo remembers. “We’d be set off first and they all had to catch us. I’d be steering, and the men’s pair would be zooming up behind, trying to overtake by cutting up the inside, with Adam shouting at me to move out, but Belinda would be going, ‘Don’t you dare!’, so I was there, aged 18, stuck between a rock and a hard place. It was just hideous but we’d stick to our guns, and after all that we’d get back and Adam would go, ‘Great piece!’ I just thought, ‘Phew!'”

“Mike was an amazing technical coach. Very quietly spoken. He also very rarely said anything like, ‘That was good.'” she continues, laughing wryly. “I remember when it was coming up to racing season and we were doing shorter pieces, one day we had to do something like ten times 500m, though I’m probably exaggerating. And we’d do all ten and he’d be there in his coaching launch, not really saying a word, and after we’d done them he’d come over and say, ‘OK, on the second one this happened and that wasn’t too good, and then on the fourth and the seventh one this other thing happened, so we’re going to do those ones again.’ So just when you thought you’d done them all, you’d have to repeat some of them!”

They rowed in a wooden Stampfli pair which Flo says was “lovely”, although who it belonged to isn’t clear, and did weights in Spracklen’s garage.

Quad scull

For the first time since 1977 (and only the fifth time since women had started racing internationally 32 years earlier in 1954) there was a GB quad, brought together by Bill Mason, who was in charge of Imperial College Boat Club in Putney. All four members of the Tideway-based crew also had solid international experience Gill Bond had stroked the GB eight in 1983 and had been coached by Bill as a single sculler for several years; Gill Hodges had stroked the eight in LA (her third year representing GB); Katie Ball had stroked the GB four in 1983 and 1984, and had also been GB’s first female junior single sculler in 1980; and Stephanie Price had been in the previous GB quad in 1977 before rowing inthe eight in 1979 and subsequently focusing on single sculling.

Although there’s no denying that the foursome had considerable pedigrees, Katie doesn’t remember them having to fight for their places in the crew and, in fact, they spent the winter racing each other in singles and double sculls just to get suitable competition. There were two or three other quick women scullers in the country at the time, but they weren’t in the area, and practicalities in an era when everyone was working of studying full time ruled out their involvement.

Women’s Eights Head of the River (2 March 1985)

The Women’s Head, where 65 crews raced, saw some of the fragmented GB groups come together for the first time with no fewer than four crews under ARA colours.

The event was won by ARA II, made up mostly of the scullers, about which Geoffrey Page wrote, probably in The Telegraph, “This can hardly have lessened the anxiety evident in many quarters about the handling of the ARA squads this winter, especially as the ARA lightweight eight, in fourth place on Saturday, were only 0.75 seconds slower than the women’s squad first eight.” While it’s not surprising that the much more experienced athletes in ARA II could beat the newcomers of ARA I (who were also beaten by a non-ARA crew that contained six of the Los Angeles Olympic eight who were no longer seeking GB selection) by 23 seconds, he makes a fair point about the openweight ARA I really not being sufficiently faster than the lightweights.

Katie Ball, who rowed at bow in ARA II says, “I think we had a couple of outings. We got Adrian Ellison [who had coxed the men’s four that won at the LA Olympics the previous summer, and says, “I think the race itself still features in my all-time top ten”] because he was a friend of Lin and Beryl’s, and Bill Mason coached.” Lin Clark adds, “This hotch potch crew was very motivated to beat ARA I!”

The 1985 head was still only raced over 4,400m, starting at Chiswick Bridge but finishing at Hammersmith. However, the Women’s Rowing Committee, which still ran the event, were actively seeking the opinions of women rowers about whether the race should move to the ‘championship’ full distance the following year [and it’s hardly spoiling the plot to say that the answer was a resounding ‘yes’ – Ed.].

The shift to 2k racing

Extending the international racing distance for women from 1,000m to 2,000m potentially required a number of major changes.

Rowing is relatively unusual amongst racing sports in the way that the same people will compete (at least domestically) over a 20 minute head race in March and a 500m/1’45” sprint in August. In running, say, different people would compete in the two types of event and would follow very different programmes and as a result you see light, skinny people racing the 5k and 10k at international track events, while the sprinters are much taller and more muscular. That said, the difference between 1k and 2k in rowing is nothing like that between even 200m running sprint and a 5k race, and GB women who rowed at the time don’t remember any particular change in their training as a result of the change in distance.

One difference that was obvious to them, though, was the size of the Eastern bloc crews. As Katie Ball put it, “The women virtually halved in size, and they became taller and taller, and slimmer and slimmer, when before they were like meatballs.” Although Britain had long recognised the value of being tall in rowing, the British team was simply drawing from women who happened to row in clubs because they enjoyed the sport of rowing, and this was a very different base to the pyramid from that in the Eastern bloc system where tall girls were identified at school through systematic testing and then drawn into a state-supported programme that taught them to row.

Whatever size you are, 2k racing does require a different race plan compared with 1k, which is more or less a flat out power sprint, especially in larger boats. Over the longer distance, the race is a power endurance sport, and going as fast as you can for every stroke rarely works, especially for athletes who are not training full time. Instead, the fastest way of covering the full course is to start fairly quickly, followed by a central section at a sustainable pace that leaves you enough ‘in the tank’ for a final sprint. As the lightweights’ coach Mike Genchi puts it, “If you go off too fast it’ll cost you at the other end. Getting an extra length at the start can cost you about two to three lengths at the finish.” This more tactical approach proved to be the biggest adjustment needed, and took a while to be understood. It was also difficult to learn for crews which were considerably faster than their opposition domestically and nowhere near the pace internationally as the effects of getting the race profile exactly right are only obvious when you’re racing people roughly the same speed as you.

The final point to be made about the shift from 1k to 2k racing is that, as FISA acknowledged at the time, an endurance event was less likely to encourage doping than a power sprint, although the short-term benefits of anabolic steroids also aided recovery which allowed athletes taking them to cope with a greater training load. While amateur rowers, like those in Britain, who had full time jobs or college courses, time was also going to limit the amount of training possible, but for the full time athletes of the Eastern bloc where time was not an issue, drug use was still effective.

Early season racing

In line with the policy set out at the beginning of the season, the main squads did a minimum of racing abroad to keep costs down.

Lin and Beryl raced more than the other crews, through a combination of self-financing (unlike the main squads which contained a lot of students, they were well-established in their careers) and their sponsorship from Playtex.

Ghent (4-5 May 1985)

Lin and Beryl won openweight doubles.

The quad raced in their singles, from which Gill Bond has a medal, and Belinda and Flo raced their pair there too.

Vichy (18-19 May 1985)

The lightweight coxless four medalled and the quad also raced.

Duisburg (25-26 May 1985)

Three weeks after their victory in Ghent, Lin and Beryl won again, this time racing lightweight. Writing in early July, Beryl described some of the pressures they were under in a wider piece entitled Me and my lightweight rowing, “My first race as a lightweight… was at Duisburg Regatta in West Germany where I weighed in at 8 stone 13 pounds. This was our first test and we had to answer all the sceptics’ questions who said we would never make the weight or if we did we would be so weak we wouldn’t [be able to] do any good. Well, results speak for themselves.”

Nottinghamshire International Regatta (1-2 June 1985)

In windy conditions, Beryl and Lin won the lightweight doubles on both days by nine and then six seconds from a Danish crew.

Carrie Wood finished second on both days in the lightweight singles, about 18 seconds behind a Belgian sculler each time. On the Saturday she was comfortably clear of the next British entry, but on the Sunday only beat Clare Parker (also racing as ARA) by just over a second.

Two ARA crews were entered in the lightweight coxless fours, finishing about 15 seconds apart on the Saturday and the Sunday, and with the faster one winning the event on both occasions.

The eight won two-boat races on both days against a Commercial RC, Ireland crew that was well off the pace.

The programme shows a number of other ARA entries in the women’s events, including two coxed fours, a second lightweight double and lightweight coxed four, pairs and singles, but it’s unclear whether these actually raced.

Amsterdam (29-30 June 1985)

The lightweight double competed under their Playtex ‘Thank Goodness It Fits’ sponsorship for the first time. Lin remembers that they lost to the French, which “needled” both the GB crew.

Carrie Wood did both lightweight and openweight singles. She and the other lightweights paid all of their own costs.

The openweight coxed four also competed. The entries list shows a number of other ARA entries without individuals’ names, but it’s unclear whether these actually raced.

Lucerne (12-14 July 1985)

Lin and Beryl were second in the lightweight doubles behind the French (again) but only by 0.08 seconds. Basically, they were the same speed as their rivals, and in this situation, of course, it’s the crew that races better which wins.

National Championships (19-21 July 1985)

All of the squad GB crews entered Nat Champs, and all won their events convincingly.

Beryl and Lin won the lightweight doubles by 24 seconds ahead of the only other entry, but also doubled up in openweight where they deadheated in with former internationals Kate Holroyd and Jean Genchi in a straight final that was 40 seconds faster than the lightweight one.

“The lightweight women’s sculls proved an inspiration for Carrie Wood of Furnivall who eclipsed the field and helped herself by impressing the selectors to nominate her for the worlds team,” as Rowing magazine described it. There was a healthy entry of 17 scullers in the event.

The lightweight coxless four won by 15 seconds.

In the pairs, Belinda and Flo finished 32 seconds ahead of Kate McNicol and Alexa Forbes who were having fun after stopping international rowing following the Los Angeles Olympics.

The eight won by 15 seconds from Cambridge University (an entry that combined the openweight and lightweight fours scratched), the quad was a whopping 54 seconds faster than the next crew their three boat straight final which, as Katie Ball points out, “Just shows you how poor the standard was.”

The four also enjoyed a comfortable victory, romping home 21 seconds clear.

The 1985 GB women’s Rowing Team

The team was:

Eight

B: Carole Collins (University of London WBC)

2: Samantha Wensley (Borough Road College RC)

3: Tessa Millar (Thames RC)

4: Susan Turner (City of Cambridge RC)

5: Anna Page (Burway RC)

6: Sue Clark (Abingdon RC)

7: Aggie Barnett (Weybridge Ladies ARC)

S: Judith Burne (University of London WBC)

Cox: Susan Donaghue (Lea RC)

Coach: Steve Gunn

Coxless quad

B: Katie Ball (Lea RC)

2: Stephanie Price (Thames RC)

3: Gill Bond (Imperial College BC)

S: Gill Hodges (Tideway Scullers’ School)

Coach: Bill Mason

Coxed four

B: Ali Bonner (Oxford University WBC)

2: Sarah Hunter-Jones (Thames RC)

3: Tish Reid (Oxford University WBC)

S: Ann Callaway (University of London WBC)

Cox: Lesley Clare (Oxford University BC)

Coach: Noel Casey

Coxless pair

B: Belinda Holmes (Weybridge Ladies ARC)

S: Fiona Johnston (Marlow RC)

Coach: Mike Spracklen

Lightweight coxless four

B: Paula Nock (University of London WBC)

2: Sally-Ann Petrie (Twickenham RC)

3: Claire Moore (Civil Service LRC)

S: Melanie Holmes (Weybridge Ladies ARC)

Coach: Mike Genchi

Lightweight double scull

B: Lin Clark (Sons of the Thames RC)

S: Beryl Crockford (Sons of the Thames RC)

Coaches: Mark Hayter and Jim Clark

Lightweight single scull

Carol-Ann Wood (Furnivall SC)

Coach: John Tomkins

At the Championships

The Championships provided good racing conditions with Rowing magazine reporting that, “Competitors expressed pleasure at the fair conditions and winners came from a wide variety of lanes,” although it was a bit blustery for the women’s first round heats.

Lightweight double (1st out of 8)

The story of the 1985 World Championships is, of course, the lightweight double which won GB’s first women’s gold medal, some 31 years after women’s international rowing officially began in 1954, and ten years since the same two women had scored GB women’s first win at a major international regatta at Mannheim in 1975.

According to Geoffrey Page in The Guardian, they won their initial heat “with impressive ease,” which doubtless explains why their time was nine seconds slower than that of the French, who won the other heat. He added, “A medal on Saturday [in the final] must be well within their reach.

The crew must have known he was right, but they weren’t just after any medal; they were there to win, so how could they turn round their two recent defeats at the hands of the French, which at best suggested that they were the same speed? The answer was in how they raced over the 2k course.

Beryl, who was at stroke, had always had a reputation as the hardest of hard racers, which is certainly an invaluable quality in rowing. However, when Mark Hayter had started coaching her as a single sculler in 1980, he remembers that one of the main things he contributed was helping her to be aware of how she could phase a piece or a race, rather than just go flat out. And he returned to this point again in 1985, when it was even more important given that racing was now over 2,000m. Lin fully understood this, but the challenge that she, Mark and Jim had was in persuading Beryl that less in the first part of the race led to more later; for a woman who had justifiable faith in her power, attitude to hard work and sheer guts, it was almost an anathema for her not to give it her all from the word ‘Go!’.

Lin remembers Jim’s strict instructions to go off at below race pace for the first 500m to let the French think that they had broken the GB crew, but although she was making the calls, Beryl was the one setting the rate.

On this, the most crucial of occasions, she delivered exactly as Thor, Jim and Mark had advised; when it came to the final, the French, as expected, sprinted hard out of the blocks. After 500m, “We were behind the French, but by no more than if we’d been going flat out,” Lin recalls. “When I then heard them go for a push at that point, we went with them, but straight after this push we pushed again, even harder, and this time with reserves in the tank. We caught them up and then overtook them. They seemed visibly shocked, panicked, shortened up, and went for another burst. But we just lengthened our strokes and I called for us to push the finishes, and I was surprised how easily we cleared them.”

Having gained the lead, “I was keen to keep doing what we were doing because it was effortless,” Lin continues, “So as we got clear I called for a further lengthening and relaxing. It was so great to see the French struggling! It fed us as we continued to move away. We so wanted them to suffer for our previous defeats.”

Looking back on their perfectly-paced race Lin adds, “It was unlike any other race we had been in that year because what we were saying basically boiled down to me saying, ‘I can’t believe we’re still going away, so down two,’ and Beryl called back, ‘I’ve already gone down two.’ I was just loving it and knew we had so much left so I said, ‘Then go down another two.'” But it was an amazing moment when we crossed the line, though Beryl’s words were, ‘I feel a bit cheated, it didn’t hurt.’ And I said to her, ‘For goodness sake Beryl, this is my idea of winning because it hasn’t hurt!”

The French crew seems to have done exactly what the British duo’s coaches had warned them against, and suffered the consequences as Lin and Beryl turned their eight second defeat by them in Lucerne into an eight second advantage with West Germany also overtaking France later on. Lin recalls, “We just watched as the Germans and the French battled it out for silver and bronze.”

A very short clip of them leading their final can be seen a minute in to the video below.

The way they approached the 2,000m race wasn’t lost on Peter Ayling who wrote in Rowing magazine, “One pays full tribute to the maturity of Beryl Crockford and Lin Clark in the manner in which they achieved their gold medal success.”

Also writing in Rowing, two-times Olympian Jo Toch summarised the race from the outside, “Clark and Crockford took a confident start and although sitting a length down on the French at 500m, looked comfortable and capable of avenging their defeat by this crew at Lucerne. At 1,000m they began to push and moved through, showing the maturity gained through their many years of top class international competition. By 1,500m they were a length clear and needed only to keep their cool to become Britain’s first women’s world champions. The French had no response [they had the slowest last 500m of all the crews in the final – Ed].”

This was the first medal achieved by a British women’s crew at a World Championships as well as being the first gold for GB (Britain’s only previous World medal was Beryl’s silver in the single scull in 1984; a bronze had been won by the GB coxed four at the European Championships in 1954).

Jo Toch added that their win was, “An outstanding achievement. It was a triumph of guts and determination and provided inspiration for every member of the British women’s team who began to rush for body fat tests [journalistic exaggeration there, although perhaps this was a largely personal idea as Jo herself returned to international rowing the next year as a lightweight – Ed.]

After the Championships, Playtex threw a celebratory tea party for the golden crew, with cream cakes, of course, which Beryl described as adding moral support to the financial and physical support already supplied.

Lightweight four (4th out of 8)

The lightweight four finished fourth and last in their heat but in a time which would have placed them second in the other heat. They then came third in the repechage from which the first four qualified; they were through to the final.

“The coxless four… gave us a darn good run for our money in their final,” wrote Peter Ayling in Rowing. “They led at 500m and up to 1500m were challenging for silver or bronze and were only pushed out into fourth place in the final 250m.” Jo Toch noted how, “On their performances during their advance to the final, the British looked capable of no higher than fifth place,” but continued, “However they took their chance on an early lead and their brave attack almost gave them a medal. In the last 500m, having been overhauled by the West Germans, Americans and Australians, Holmes was still attacking to get back on terms. This was a fine performance with the British crew racing above the level that earlier results might have suggested.”

Geoffrey Page described their result as “highly commendable”.

More importantly, Mike Genchi their coach was impressed with them too. “They did really well. It was [quite something], to get to the final and be close to a medal, he says, adding, “They were such young girls, but they were talented and that four was a really good technical four, good length. I thought a lot of them.”

Eight (6th out of 6)

The eight had a straight final which is rarely a satisfactory situation for anybody, particularly a crew which is new to international competition whose primary goal for being there is to gain experience at this level.

The first four crews finished within six seconds of each other with a photo finish for the bronze medal. The fifth-placed crew was 24 seconds behind this tussle, and the GB eight came last, 11 second after that.

As Jo Toch put it in Rowing, “The British eight, labelled a development crew, could never get on terms with the rest of the field. One wonders how useful the experience really was to them as this was their only chance to race because of the low entry.”

Stroke Judith Burne agrees that while it was a good idea to run a development eight through the year, they shouldn’t have been sent to the World Championships. “I was embarrassed – it was just awful,” she says.

Coxed four (8th out of 8)

After travelling to Hazewinkel in style in their coach’s Rolls Royce, things went downhill from there on for the coxed four. After finishing fourth out of four in their heat, they were sixth and last in the repechage.

“In the small final, the British crew lost an initial psychological advantage over Britain’s [perennial] arch-rivals the Bulgarians, who arrived late at the start. Due to equipment problems the British women had to request a delay,” Jo Toch wrote in Rowing. “However, when the race did get off, [they] were unable to match the pace of the Bulgarians.” The GB crew finished over 12 seconds down.

Tish Reid was stunned. “I couldn’t believe that we weren’t the most amazing four in the world, because we’d beaten the pants off everybody that we met in the UK. And also if ever we met anybody when we were training on the Tideway and agreed to do a piece with them, we’d give them a three or four length lead and would always go steaming past them before half way. So that was very much my expectation. We’d been selected to represent GB because we were so fast, and suddenly it all became very clear that was definitely not the case.”

She continues, “I just went around in a bit of a haze, not believing that we couldn’t hang on to anybody. And what I found very crushing was that nobody expected us to do any better. It also didn’t seem that anybody wanted to really do anything to make a change either, which was a real revelation.” This last point was also one that struck Tessa Millar, the only experienced member of the eight, who reflects, “Radical things needed to be done but nobody was really interested.”

Coxless Pair (9th out of 10)

Although the pair’s result of ninth was numerically lower than that of the other two openweight boats, the eight and the coxed four, they were much closer to the crews ahead of them and they weren’t last.

In their heat they came fourth out of five, and then finished third in their repechage from which only two crews qualified for the main final.

Geoffrey Page described how, “In the small final the British crew, which matched the experience of Holmes with the young potential of Johnston, rowed solidly but seemed unable to change pace… With 500m to go, Johnston and Holmes were with [Russia and Australia] but failed to race them home, finishing a further length and a half back.” Russia won, with Australia (one of whom had been a bronze medallist in the coxed fours at the 1984 Olympics) second. The GB crew finished over 30 seconds ahead of the Koreans who were on a rapid learning curve about the whole sport of rowing in advance of the Olympics being held in Seoul in 1988.

Flo Johnston recalls, “Mike [Spracklen, their coach] was quite pleased with us because we’d done better than the other heavyweight crews, and I think Belinda was relatively pleased with it too; I was just doing as I was told!”

Lightweight single (11th out of 16)

Carrie was third in her heat, third again in her rep which qualified her for the semi-finals where she needed to come third to reach the main final. “John and I decided that I should just go for it in the semi. He said, ‘You can do a comfortable semi, and then get your best possible result in the small final, or you can give it everything in the semi to try and make the grand final and then you’re guaranteed sixth place, but if you don’t make it you risk being so knackered for the small final that you’re 12th.'” In the end, she came fourth, just two seconds off qualifying. “I didn’t have a final push because we hadn’t really worked on that,” she remembers.

“In the small final Wood sculled competently,” Jo Toch wrote in Rowing, “But had less base pace than her opposition. She had the satisfaction of beating the Russian sculler into 12th place.” [This was a rare example of anyone from the Eastern bloc being entered in a lightweight event, and not surprisingly didn’t encourage a repetition – Ed.] Jo added, “The standard in this event was very high. The first four scullers would have challenged for the open women’s final.”

Carrie points out, however, that her final placing of 11th was one better than Steve Redgrave’s, who was also single sculling that year and came 12th.

Peter Ayling said, “I admired the gutsy way Carol-Ann Wood tackled her racing. She certainly lacks little in determination and if someone will only direct her enthusiasm into some planned training programme she might well climb up the world placings.”

Quadruple scull (11th out of 11)

As with the openweight sweep crews, Britain’s foray into quad sculling again showed that we lagged behind the rest of the world.

After coming last in their five boat heat, the quad took fourth place out of five in their rep, beating China, but then finished last in the petite final (behind China, although as someone pointed out, “They do have more people to choose from”), in a time some 32 seconds slower than that of the gold medallists in the main final.

As Jo Toch described it in Rowing, “In the small final the British crew were never able to maintain contact to really race the other crews. In an exceptionally competitive event, their lack of international sculling experience was a telling factor.”

By way of analysis rather than excuse, Katie, who went on to have a very successful coaching career, recognises now that one of their main problems was that, “We were such individuals and to make sculling crews work, you don’t need the greatest single scullers, but you do need people who can blend together, and we didn’t do that well at all.”

Roundup

Richard Burnell, in a newspaper clip probably from The Times, said he considered that, “[The British openweight] talent seemed to be spread too thin,” adding, “The four, pair and eight all had merit and between them might have provided material for one really good crew.” However, logistics prevented this to an extent, and also had this been done, the future development goals that Rosie Mayglothling set out at the start of the year would not have been met.

Geoffrey Page was also gloomy, writing that the openweights were “demonstrably not strong or fast enough at this level” and speculating, “Perhaps the time has come for a higher qualifying standard for selection.”

Peter Ayling’s opinion in Rowing was that, “The first year of a new Olympic cycle saw fundamental changes in women’s racing with the extension of the course to 2,000m and the introduction of lightweight rowing. British women have long encouraged both these developments, believing more success would be possible where there was a greater emphasis on technique and endurance rather than explosive power. Unfortunately the dismal performance of the [openweight] squad showed that success is not likely to come any easier. In general the top nations reasserted their authority with the Eastern bloc as dominant as ever.”

At the end of the Championships the fragmented women’s squad had a group meeting. “It was meant to be about ‘What next?’ because it had been a very difficult year and everyone was very miserable,” Tessa Millar recalls. “However, the lightweight double winning their gold was just amazing because it proved that British women can do something and we can get some girls over the finish line first, and it was great that there was some sunshine on the horizon because just to train and train and not to get any success was awful. I think everyone was very pleased for them.” Exactly how this inspiration could be harnessed for practical effect in the openweight squad remained unclear, though.

World Junior Championships

Having previously been called the FISA Championships for Juniors, because FISA had maintained that there could only be one world champion in any boat class (and therefore it was the winner of the senior, openweight event), the first so-named World Junior Championships took place in Brandenburg, East Germany from 7-11 August.

The racing distance for junior women was increased from 1,000m to 1,500m, the distance over which junior men raced. Some had predicted that this longer distance would produce huge winning margins, but this wasn’t the case. Entry numbers, however, continued to be disappointingly low.

The GB junior women’s team comprised two crews.

Coxed four (5th out of 6)

B: Vikki Filsell (Mark Rutherford School RC)*

2: Kim Thomas (Weybridge Ladies ARC)**

3: Anna Durrant (Mark Rutherford School RC)*

S: Katie Sanson (Weybridge Ladies ARC)

Cox: Sarah Birch (Weybridge Ladies ARC)

Coach: Doug Parnham

* denotes a previous cap in the GB junior team.

The crew was last at 500m but rowed down the French to finish fifth.

Coxless pair (4th out of 5)

B: Lisa Roche (Northwich RC)

S: Lise-Lotte Osborn (Marlow RC)

Coach: John Bell (Mark Rutherford School RC)

The crew, “Was dropped by the leading three crews early on, but won their private battle with the USA to finish fourth,” according to Rowing.

© Helena Smalman-Smith, 2018.